Disinclined to write, I wandered the ghats and streets at the northern end of Lake Pichola. Later I’ll dedicate a post to the lake, so have focused here on faces, mostly human.

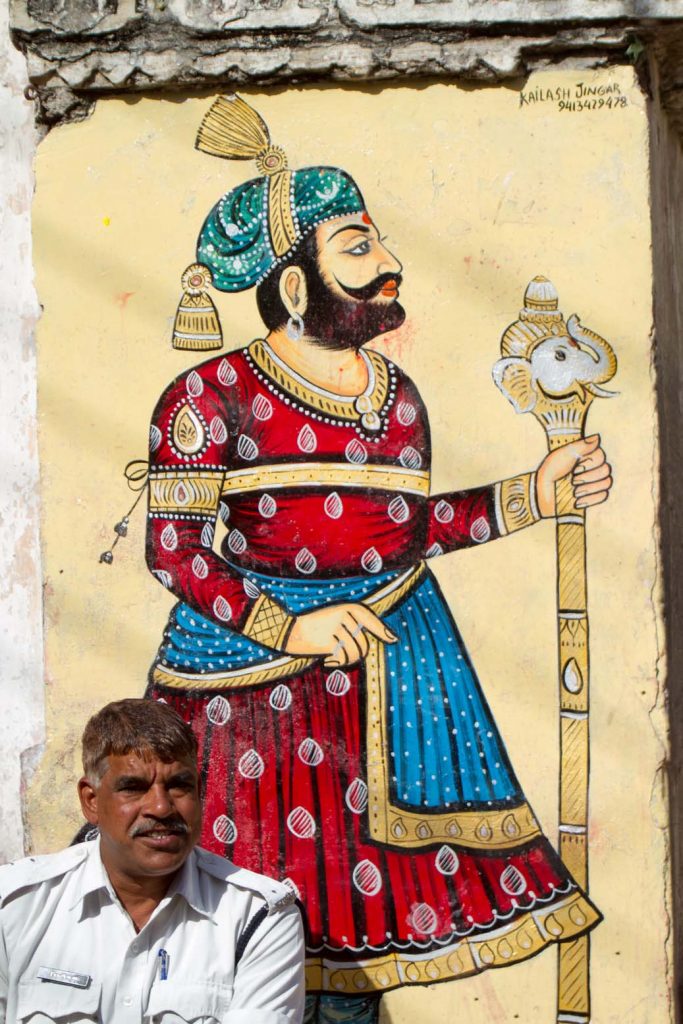

Though it’s a touch off-focus, I couldn’t bring myself to ditch this picture: such nobility of bearing. And so quintessentially India.

This woman could be a model in the west, and not just for her facial beauty. I framed too tight, so you don’t see her majestic bearing as she shimmers along Gangaur Ghat, builders rubble in a cloth cushioned basket on her head. As a young man I’d occasionally be asked by women in the fields south of Delhi to help them get bundled firewood or sugar cane into place. I knew, from humping bags of sand and cement on building sites to pay for that first trip east, those loads to be well over a hundredweight. A smile and nod of thanks, and they’d walk proudly away with a posture and gait western women can only dream of.

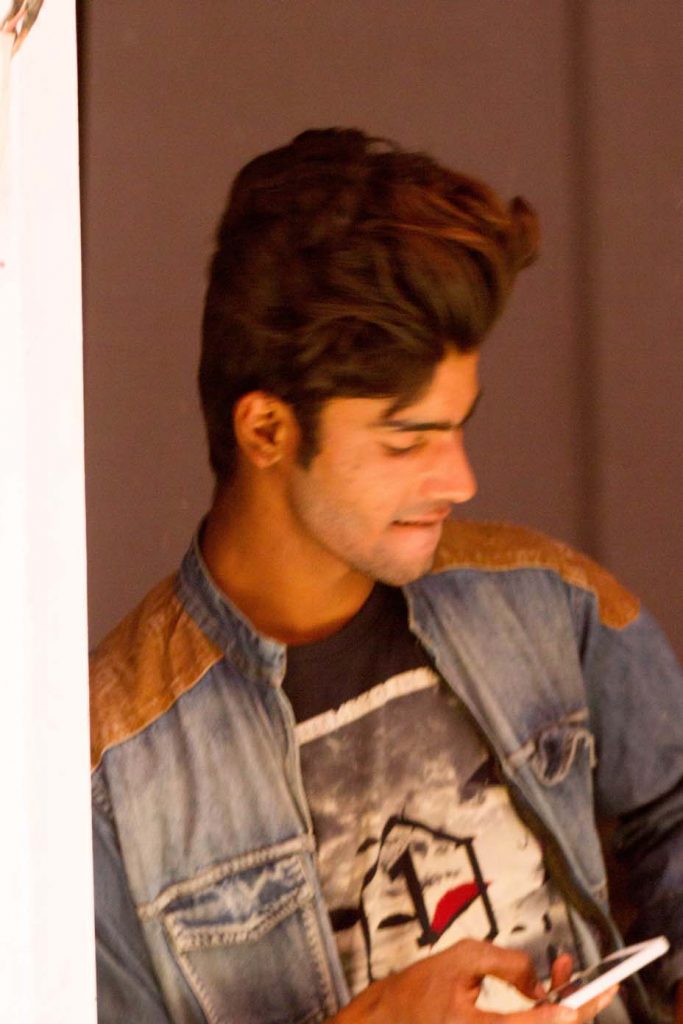

Here’s Johnny – of the Johnny Tea Center, a windowless concrete cell on an alley in the north west of town. Johnny does the meanest ‘cafe masala’ I ever tasted. He uses instant but it knocks most of the town’s so-called espressos – I’ve sampled a good few – into a cocked hat with its triple strength, and wallop of ginger at back of the ferret. I’ve paid four visits and there’s always something afoot, if only venomous glances between Johnny and no nonsense wife, who, besides taking care of the samosa end of the business, does a fine line in bell peppers stuffed with potato and chilhi. Today I met a priest who looks like a rock star, a painter whose daddy and grand daddy had plied the same trade, and a New Englander crossing India on an Enfield Bullet she bought on arrival three months ago and intends to sell in Delhi

Johnny and his Buena Vista Club merit a post in their own right. For now, this will have to do. In the sunlight at cave’s entrance Johnny minds his stove, a mud and dung affair in a recycled ghee tin. It runs on charcoal, kicked into life as needed by hand-rotated bellows feeding an air pipe soldered in, a few inches up the tin’s side. Wife and clientele sit or squat in the interior gloom, for the time being safe from my lens. Tomorrow I’ll be back with flash gun.

Rajasthan’s havelis – a Persian word betraying yet another of the diversity of influences on the sub continent, its mores and wider culture – had tiny shuttered windows, that the womenfolk might observe life without being seen in return. Those days are largely gone, but an elderly woman or less commonly a man can still often be seen watching life go by, if we only get our eyes up from street level.

Finally, life in India involves a great deal of waiting. (Bear in mind, next time a vendor tries to ‘fleece’ you, that you may be his/her sole customer that day, week or even month.) There are two common ways of filling in the time. One, especially favoured on the lowest rungs of the ladder, is sleep. Last October I made the mistake of accompanying Pappu in Bundi to the free hospital for his fortnightly jab to deal with some blood condition. In a crowded reception where motorbikes glided in and parked, and dogs came and went at will, hundreds of people waited. And waited. After two hours I was going up the wall. We were far from any part of town I knew, and this neck of the woods had all the charm of an industrial estate – which in point of fact it was. I’d forgotten how to wait, you see, so was pacing up and down with furrowed brow, till a radiographer called me to the door of his small office. He pointed to a couch and gave me to understand I should lie on it and take a nap. How could I have forgotten the art of sleep, and on a hot afternoon in this of all countries? The time sailed by, though it would be another two hours before Pappu came to claim me.

But the other most common time-killer, favoured by the petit bourgeois, is reading the paper. Shopkeepers are forever at it, closely followed by tuk-tuk wallahs.

The end.