It’s tricky, negotiating a way down this baked and rutted track to a lake spied from the road. I have to calibrate. Too little power and I come a cropper as front wheel fails to steer round or over the ruts, pitching the machine sideways. Too much and I fly over the bars. (How do I know? Because I’ve accomplished the first, with minor but painful consequences, on similar terrain in Vietnam and the second – same principle, without the exacerbating factor of small wheels – on a push bike in Sheffield, 1962.) It doesn’t help that ten minutes ago I rubbed on the factor 50, leaving right palm with less sure a grip on the throttle than Scootering Today deems optimal.

I was at the bike hire at seven-thirty sharp, passport for deposit. The map they gave me (no skid lid) was about as much use as a toy globe but what care I for that? As long as I get from city to hill and pleasant vale I’m not particular about precise route or destination.

Udaipur is hotting up, with increased desperation – now’s the time for driving bargains – on the part of vendors who know the tourist season’s almost over. From now to August rains Rajasthan will be a furnace, frequently hitting the early fifties here, higher in the north and west. Provided I avoid sunstroke (sarong to back of neck) and sunburn (aforesaid factor 50, frequent and liberal) coasting in the breezes while taking in the rustic delights will be just the ticket.

This is the desert state – of camel fair, snake charmer, gypsy dancer and atomic bomb test – but here in the south we’re as far from the Thar as is possible. Udaipur is Keswick to Rajasthan’s lake district: arid in the hills, yes, but with lushly river fed valleys and richly arable soil in the lowlands. Though too dry for rice, wheat there is aplenty, and right now it’s being harvested.

Around nine I snap a field of swaying cereal, in one corner a small and tidy farm. A man in his prime hails and waves me in for a closer look. “Welcome”, says he, as I close his well tended gate to exchange namaste greetings: palms together as in prayer, joined thumbs to forehead. I note that word, when he knows no more English than I do Hindi. Neither rich (no tractor) nor poor (a water buffalo he proudly invites me to photograph) I warm to an open-heartedness I’ve encountered over and over in rural Asia, and ask myself – given that tourists will be few and far between in his neck of the woods – how big my vocabulary in a second language would have to be before it took in the word for welcome.

No FB. No email. I don’t do this for just anyone but here make an exception. I take a risk, miming a request that he write his postal address on my proffered notepad, but he is literate, albeit in a Hindi script I’ll have to get translated. Looking him in the eye with one hand on heart, other simulating plane climbing sky from England to descend on India, I assure him I’ll send prints. He gets the idea, and that it’ll be a while.

He wants a shot of his wife. (No, not “wants shot of his wife”!) She’s less keen but he’ll brook no gainsay on the matter. Note her banglets, probably containing a little of the silver Rajasthan’s capital, Jaipur, is famed for. In the seventies you saw peasant women in the fields, barefoot but with all worldly wealth carried thus, a kilo and upwards of solid silver welded above the ankles. Greater trust in banks has changed this. Greater trust, and credible reports – as Indira Gandhi’s far-sighted but brutal protectionism sent inflation skyways to spark Naxalite Maoist land grab in the sticks, Moscow leaning state governance in Kerala and upsurge in dacoitry just about everywhere – of robbery by amputation.

Before I go I’m offered water. Though not overly fastidious about street food, or salads washed in local water, I avoid drinking the stuff. (In the seventies I was in Asia a year. After a severe but short bout of amoebic dysentery in Kashmir on entering India, for which I took only soda water though tetracyclin could – like diamorphine, cocaine and LSD – be had for the asking in at least one Srinigar pharmacy, I was right as rain for the rest of my trip: drinking local water all the way. But I was a younger man and besides, being sick a week or two is just a drag on a long visit; a disaster when you’re here only a month.) He isn’t remotely offended by my refusal. He, his wife and the other farm workers wave me off as I start up the scooter and head for the hills.

For a while it’s still verdant. As when I spy the pretty lake whose challenging path of access I opened with …

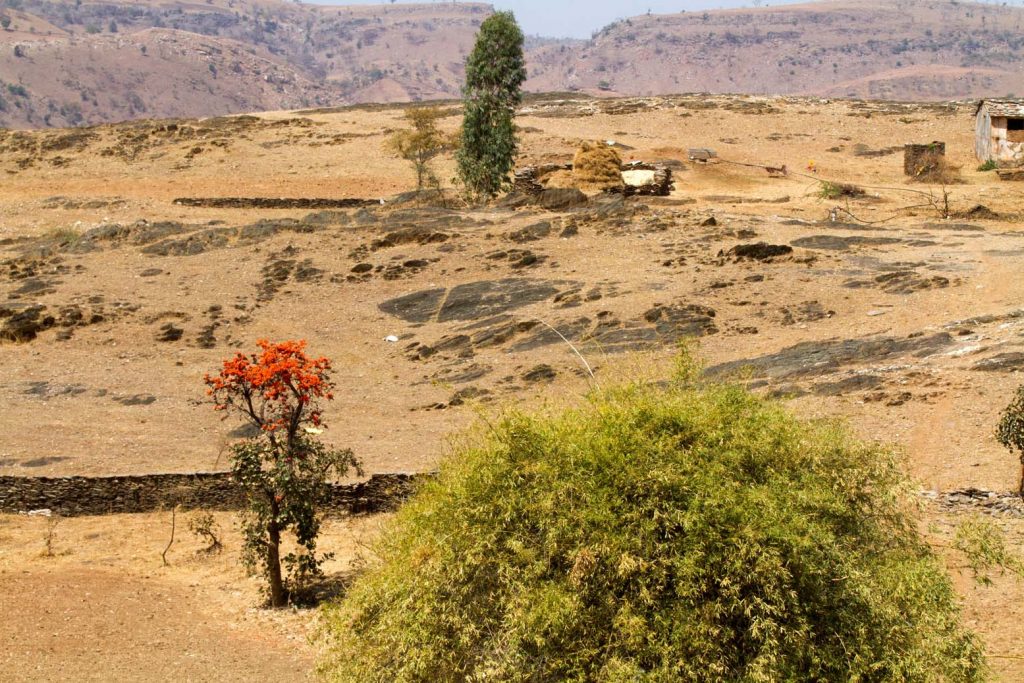

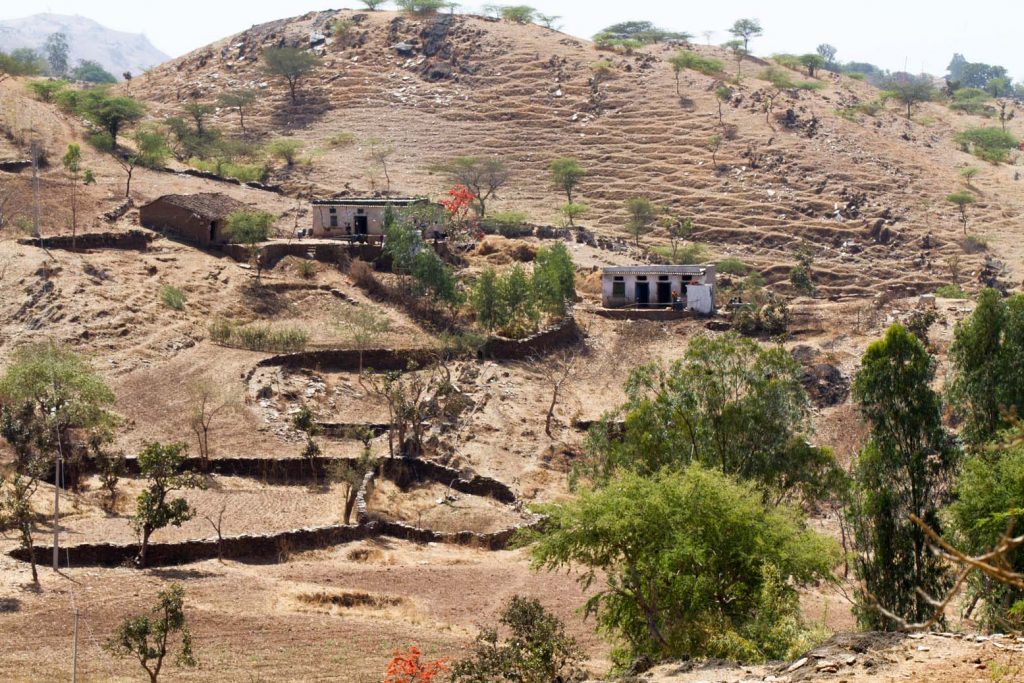

… but as you can see from that last image, things are about to get a lot more arid as I continue onward and upward. Before I do that, however, I follow the dirt track round to a hamlet on the far shore.

At first I’m met with what appear to be sullen looks but I’ve found this to be almost always a misreading. In Vietnam I visit such backwaters often and find that by smiling a great deal and speaking in my own tongue the initial perplexity – that’s invariably what it is – soon vanishes as they reply in theirs. I’ve written before about this and recommend it when, in the Global South, you’ve no language in common. Just beam radiantly as you jabber away in English, French or whatever they sqwawk on your own patch of dirt. Usually I’m more or less on-topic but if I dry up, I recite poetry or voice whatever random thought runs through my head. It’s marvellously liberating; deeply therapeutic. And as animal lovers know, speech has many channels beyond the verbal. I’ve had great ‘conversations’ in such circumstances, each party speaking their own language.

As I climb the vegetation gets sparser, more desert-like. Palms, cacti and vicious thorns come to dominate. Cows and buffalo give way to goats and, more rarely, sheep. Most telling of all the farms are visibly more meagre, though most people look well fed and clothed.

A couple of times someone approaches the road, load on head. This woman for instance. I take the long shot then watch for several minutes as she crosses in front of me to glide purposefully over the wilderness on the far side till she’s a speck in the distance. As I’ve found elsewhere, such as Northern Ethiopia and Tenerife, arid terrain takes a little getting used to. At first it repels the eye used to greener and wetter landscapes. Then, as our gaze grows attuned, it reveals its own and very particular beauty.

I stop at what I call a trading post. Again the initial blank looks give way to smiles and mirthful posing as I approach with customary grin, waving camera kit the size of a pair of house-bricks but to their eyes vastly more alien.

On my way up I’d passed a dead man lying in the road, a jeep parked up with two men beside it. I looked quizzical. They shot a returning gesture I couldn’t decipher. I recalled a time forty-two years ago, hitching through the hills of Maharashtra. A girl in her teens, shabbily dressed and dark of skin, lay lifeless in the road, dried trickle of blood from mouth and nose. My Sikh trucker pulled out to avoid the boundary of stones lain around her. Was he not going to stop? His face hard, he gave me to understand – by withering look, dismissive wave and one gutterally spat out word, gypsy – she was of no more consequence than the dust she lay in.

Now, coming down two hours later, this more recent corpse had been moved to the shade of a tree by the roadside, on his back. Again I stopped, wondering what to do. Then his right leg twitched. A few seconds later the left did the same. He was dead alright – dead drunk. Those thoughtful jeepsters must have moved him to avert death by sunstroke in the worst case, the mother of all hangovers in the best.

The villages are getting bigger and richer. A shop I stop at for water doubles as a tailor’s. As is so often the case, the only menfolk to be seen are less gainfully occupied. But get that motor, extrinsic to the sewing machine and driving it by a flywheel. Over and over you see such setups in the Global South: simple, hence reliable and repairable, technologies ingeniously applied in ways that make for easy repurposing. Count on it: that motor will have served a dozen distinct functions, and been patched up and sent back into action a dozen more, before it’s finally sent to the great scrap heap in the sky.

Cows aren’t revered here for nothing, you know. Besides milk and ghee – and leather, though respectable Hindus don’t speak about this, and would as soon cut off a hand as offer it to an untouchable tanner – the dung serves as fuel. This one’s for Brian. Himself in India, on business, a few days ago he FB-ed a shot of cow pats on sale in Calcutta. Those will have been from rural Bengal but the wholesale end of the operation will be much the same there as in Rajasthan:

There are other uses for cows too, as I discover once I’m back in the green and watered.

Holy they may be, but no farmer is daft enough to believe them capable of taking the long view. I saw several ingenious ways of ensuring the hay being harvested alongside the wheat is not devoured prematurely, leaving nothing for the months of drought ahead. I like this one best.

I like it even better when a bus stops down the road to disgorge a bunch of smiling schoolgirls.

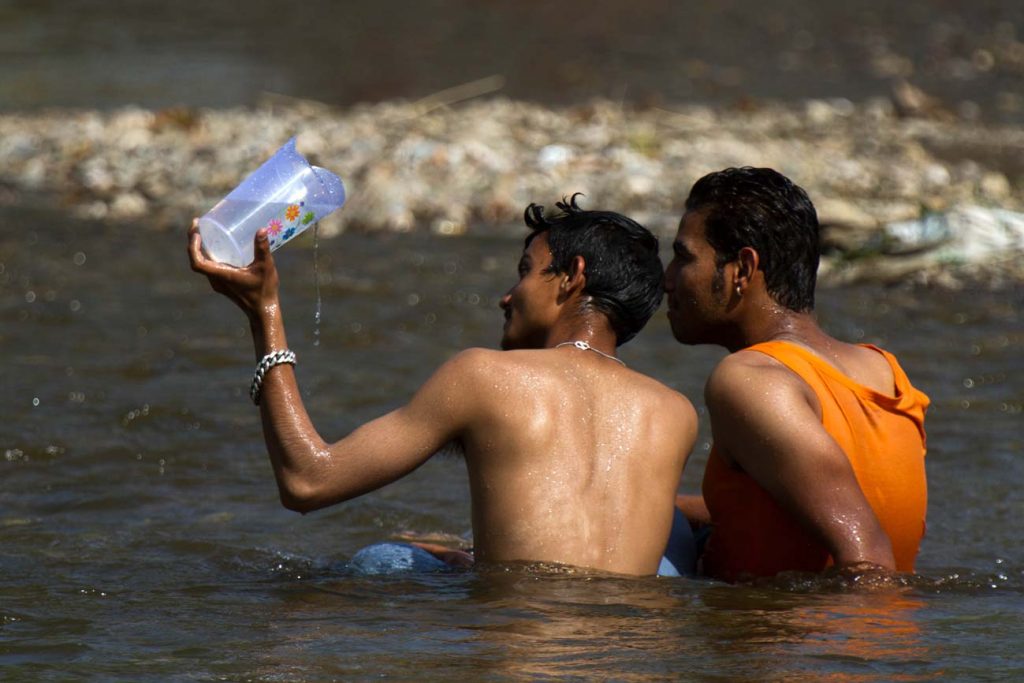

By waters idyllic I snap egrets yet again.. They take to the air as a truck rolls to a halt on the gravelly bank opposite. Three men leap out, two to play. While Mr Sensible The Driver washes clothes, his callow assistants laugh and frolic. All good clean fun.

All in all, a most satisfying spin out in the countryside. There’s much I’ve reluctantly had to leave out, this post being already way too long. Most important of the omissions is my descending on a brickyard in Mid-Nowhere. For reasons personal and historic I’m drawn to brickyards, but my encounters at this one must await another post.

Namaste, folks.