Below. The highly erudite author, warped by wide angle lens.

Earth is 4.7 billion years old. Six million years ago the collision of two tectonic plates, Philippine and Eurasian, thrust Taiwan clean out of the Pacific Ocean, the way a similar crash – Indian sub continent with Eurasia – gave us the Himalayas.

(I did the sums. If we represent 4.7 billion years as twenty-four hours, those six million years are the past 110 seconds, i.e. the smash occurred not quite two minutes ago.)

In the northeast corner of Taiwan’s Taroko National Park, at Quingshui Cliffs, you can see one result of that titanically upward squeeze where a kilometre of precipice plunges into the Pacific, continuing in the same no nonsense manner below the waves. A few hundred metres out, the sea bed is already three kilometres down and falling.

Here’s where my miniscule presence inserts itself. Night one of my three nights of wild camping in Taroko – the last three, as it happens, of my sixty-fifth spin round the sun – saw me on a semi sheltered observation point. Below me the surf hissed and boomed on a narrow strip of shingle at foot of Quingshui to give scenes like these …

… all taken within an hour of waking. The night being dry, I hadn’t even pitched my tent.

Above me, mountain ridge and peak …

… while, slightly above and a little further below, road and rail feats of engineering scarcely less impressive wowed me over my coffee:

I’m cross with myself over that last pic. I had better, with train more fully emerged, but lost them to fat finger syndrome and steep learning curve on photo editing with smart phone and the Snapseed app. Stupendous feats of human intervention are part of the Taroko story. Against the vast scales of time and geological sculpture – local signage makes frequent allusion to nature as artist – the footprint of homo sapiens sapiens may be infinitesimal, but it’s heroic all the same.

Take that dude above, his sculpted likeness looking over Jingheng Bridge at a Liwu (“lee-woo”) crashing its whitewater course down to the Pacific, ten miles distant.

Chiang Kai Shek? Sun Yat-sen? Nope. It’s a chap named Heng, an engineer by trade and the most senior of 450 men killed in the construction of Central Cross Highway, whose bridges and tunnels, both depicted in earlier posts, not only carry an excellent road through some of the planet’s most thrilling scenery but take it right across the mountainous and hitherto impenetrable forest interior to form the island’s sole east west crossing, other than the lower and shorter routes at its tapering, northern and southern tips.

Central Cross Highway was built to replace an earlier single track – largely unmetalled and its bridges in any case too weak for military transport – from a Japanese colonial era terminated by Fat Boy and Little Man. (Though truth be told, neither were dropped to end WW2 but to show Stalin who’d be top dog in the new world order.)

Chiang Kai Shek, fearful of invasion and control of the ports by a not yet nuclear China, ordered its construction in 1951. By 1957 the road, tunnels and bridges – those last not only visually awe inspiring but capable of taking the weight of rapidly mobilised tanks – were completed.

These days Central Cross Highway, more commonly if prosaicly known as Highway 8, does more than ferry tourists by coach, car, scooter and mountain bike into the gorge. It also carries truckloads of cement, marble and other inorganics from the east’s quarries and mines to the more developed and mineral hungry west coast. They drive 24/7, these truckers, their revving gear changes and hissing air brakes joining the sounds of ocean, roaring river and the jungle’s night symphonies as I laid my head to rest in nooks much visited in the day for their jaw dropping vistas, but deserted come nightfall.

I digress. The signs don’t tell, but I’d guess most of those 450 deaths were from the sheer falls of our nightmares, from tropical disease and snakebite, and not a few from an overly casual approach to dynamite. Heng’s exit was by none of these routes. Just days after a typhoon, he went up to survey the damage. For reasons I’ll get to, Taroko Gorge is prone to landslip even before we factor in typhoon, torrential rain and earthquake – frequent visitors all. One such monumental slippage of storm loosened rock ended the life of Chief Engineer Heng, hopefully crushed in an instant but possibly buried alive. All in the line of duty.

Taroko Gorge, twenty miles southwest of Quingshui Cliffs and host to my nights two and three pitches, was formed by those same forces and at the same time – just over one and three quarter minutes ago on that twenty four hour clock. Mountains thrust up rapidly, and in geological terms recently, tend to be steep; the incessant scrub and scour of their rivers eroding even the hardest rock given a few hundred millennia to do the job. The Liwu and its tributaries descend mountains still rising at 2-3 centimetres a year, bringing boulders – igneous, morphed over aeons into limestone and thence into marble – weighing hundreds of tons down to nestle precariously atop weaker, sedentary strata. The marble brings wealth to modern Taiwan, but these unstable stone stacks make Taroko an Aberfan in waiting, though without need of human agency.

I mentioned typhoons and earthquakes – mild instantiations of the latter having twice woken me from bunkbed slumber. You need a permit for Taroko’s higher treks. They’re not hard to get but lone hikers are frowned upon, while routes with rocky overhangs, which is pretty much all of them, get closed after heavy rain or earthquake above Richter 2. Oh, and typhoons can and do lift climbers from ridges, only to abandon them in mid air, their last moments spent contemplating a ravine floor rushing to greet them at thirty-two feet per second squared.

*

Here’s my night two home. Surrounded by trees and bushes, the insect life at dusk scrubbed any hope of repeating night one’s tentlessness, deet notwithstanding. With no grassland to hand – risk of snakes multiplies once you leave open ground – I pitched on this platform, again close to a beauty spot; this one overlooking the Liwu.

Here’s the view ten metres away:

And here’s the view from that speck of bridge, scene of this post’s opening selfie.

That evening, under a half moon and many stars, I again walked the gentle sway of this crossing. Stopping at the curving nadir of its shallow arc to gaze down in wonder, the night air and river’s music sent me into spontaneous meditation. I stayed rooted for close to an hour before making my way back to firm ground and night shelter.

*

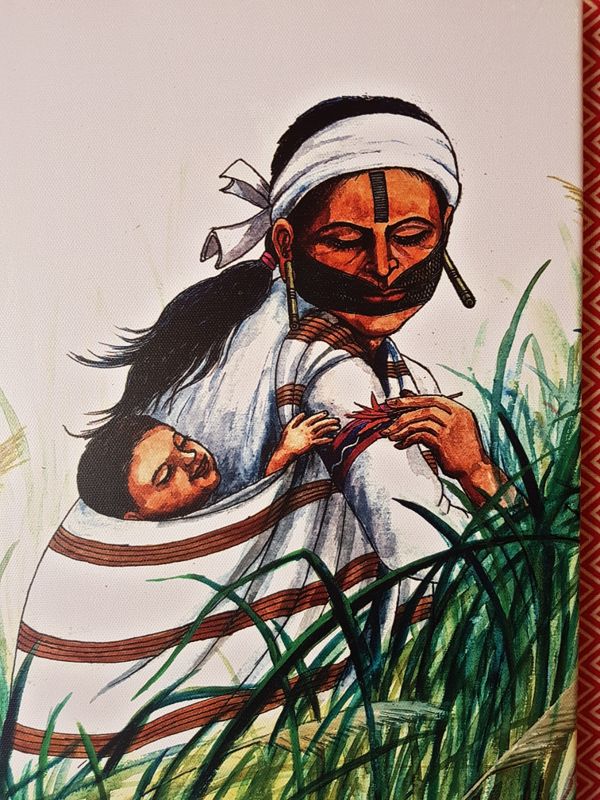

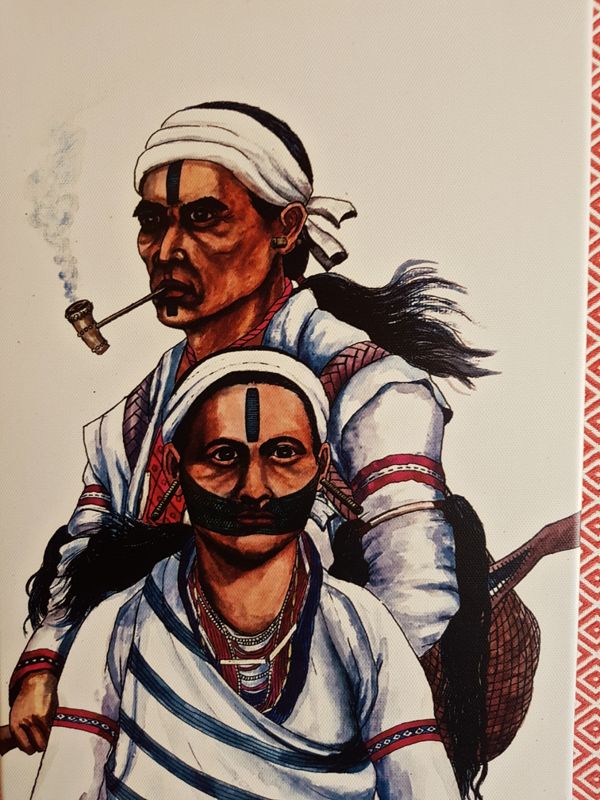

Around the time the second Jacobite Uprising was crushed at Culloden, 1745, its leaders carted to London for very public hanging – though not before penning odes to Lomond’s bonny banks and braes – an aboriginal tribe known as the Truku moved into the precipitous south east of the area now named after them: Taroko.

Settling at first on a terrace formed when the Liwu shifted its course a mere 6000 years ago (for an excellent discussion of how we can date so accurately, see Chapter 4 of Richard Dawkins: The Greatest Show on Earth) the Truku fished, hunted and practised slash and burn farming. As they fanned out over land not only densely wooded but criss-crossed by gorge and cliff, they cut pathways less than a metre wide, pathways still in use today, across rock faces hundreds of metres sheer.

Theirs was a magnificent presence but, as with indigenous peoples across the entire global south, one rudely halted in those few decades at the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Just before WW1, the island’s Japanese rulers, bent on ‘pacifying’ the Truku, sent expeditionary forces from west and east coasts. The two met, after arduous years in the jungle, in 1913: one consequence being the aforesaid rudimentary road, forerunner to Chiang Kai Shek’s Cross Central Highway; another that, as one of my sources laconically notes, the lives of the Truku were ‘inevitably altered’.

Those Truku not completely integrated into Taiwan’s ethnically diverse mix still live on that terrace of first settlement. Their village, high above the Liwu’s new course, is called Bulowan. Now dependent on tourism, it sports two restaurants, one of them to my knowledge offering good value and smiling service, and a souvenir shop. It has a large and tastefully laid out car park, boasts two lecture theatres – in each of which I saw documentaries on the Truku, and on the geology, flora and fauna of the region – and constitutes a surprisingly untacky base for expanding one’s understanding while taking in yet more of nature’s spectacle, in whatever direction you choose to gaze.

Here for instance is the Xipan (“sip-anne”) Dam, far below, fed by the Liwu and generating many useful gigawatts of hydroelectricity. It too was built by the Japanese and it too was improved under Chiang Kai Shek. After a typhoon wreaked havoc on the original, the dam’s directly driven turbines were replaced by a system pulling the water away from that exposed dam wall, for the gentle science of power generation to be applied in more sheltered conditions with newer and better technologies. As far as I’m aware there’s been no major mishap in over half a century – good going given the elemental forces it is subject to.

I speak of this in passing. It so happens that the spot I took this shot from, on my last day of being sixty-four, would be my night three pitch. Yes, it’s another observation platform: busy in the day, deserted at night. When I say ‘wild camping’ I really mean ‘camping with no unpleasant parting of cash’; less the way of the nomad than the opportunist, hence my fondness for Clint’s Heartbreak Ridge maxim: improvise and overcome.

A warm drizzle fell as I spread my silk sleeping bag liner on this platform. (I brought a light down bag on the off chance I went high enough to need it. In the event, night temperatures at my 1000-1500 metre pitches never fell below high twenties. I slept each night with nothing on, and only that silk liner, till early hours brought a slight but discernible dip that had me drape a thin cotton lungi across my upper body.)

As on night one, I’d planned to leave the tent under the scooter seat three hundred metres away. With the rain light, and little wind, I’d figured the pagoda style generous roof would keep me dry: a theory I never got to test. Dense foliage above, below and on every side teamed up with that tepid drizzle to create ideal conditions for mosquitos. There’s no malaria here but Dengue Fever is on the up, and in any case who wants to arise to the fact they’re not only now sixty-five, but haven’t slept a wink for being eaten alive? For now I’d staved off the tiny fuckers with near lethal – to me that is – sprays of deet but I could hardly wake every hour on the hour for a respray.

In the dark I made my decision and headed back for the tent. To add to my trials, I’d discovered the loss of a cherished head torch. (I already knew not only that juice levels on my Galaxy S7 stood at 2% but that I’d left the USB lead at Mini Voyage Hostel in Hualien City, rendering my two chargers – one solar, the other storing mains juice – useless, and the phone’s flashlight app a luxury I couldn’t afford.)

So there I was, struggling a second night with pitching on wooden slats, only this time with black night – that half moon not yet risen – and light rain amplified by rivers of sweat, all thrown in to keep things lively. What’s that you say, Clint? I used sticks, railings and all three detachable sections of a £4.99 Decathlon walking pole bought, if I’m honest, for dog intimidatory purposes but in the end got that tent up in a fashion more or less fit for purpose. I improvised, overcame, and am proud of the fact.

Actually I was still sixty-four when I awoke and struck camp. It was not yet six, and Taiwan is seven hours ahead of British summertime. Plus, I know not my hour of birth. But none of this dented my taste for celebration, and I knew just the place for it. Inside the hour I’d scootered to the third tunnel west of Tianxiang township to park just off Highway 8, and make my way along a slanting zig-zag of sharply descending path at its eastern entrance; down to yet another footbridge spanning the Liwu.

See those tiny humanoids below? They’re regulars I was about to join, my nostrils already picking up a faint sulphurous whiff, not at all unpleasant in low concentrations. At far side of the suspension bridge, steep steps to the gorge floor were fenced off, a sign declaring access forbidden due to high risk of rock falls. Bollocks to that: you’re only old once.

As had the half dozen locals – at least two of whom won’t see sixty-five again – I scaled the barrier, swung the old torso across a passingly scary gap, and made my descent on ancient carved steps; rockface to right, thin air to left.

Can you guess what these impromptu engineers are up to?

The whitewater entering at bottom edge of pic is fifty Celsius, from one of Taiwan’s countless geothermal springs. It doesn’t scald but is too hot to bear for long. By diverting cold water from the river into a series of pebble banked pools, the flow controlled by channel width and depth, the cognoscenti, each new arrival greeted on those stone stairs like an old friend returning to a favoured bar, know how to calibrate – and in a jiffy recalibrate to order – the temperature of each pool.

Made warmly – ha ha – welcome, I hot tubbed the onset of my sixty-sixth solar orbit. Selfie? Too much steam to risk it, but here’s how a younger and browner version of yours truly would have looked yesterday morning, taking the waters at Wenshan.

Ta for reading.

A ‘galaxy’ of superb photographs of wonderful scenery and an Interesting, well informed narrative. Thank you for a brief and pleasant diversion from the daily norm’.

Ha ha. The ‘galaxy’ ref had me stumped for a moment there. And thanks for reading, Chas. I did wonder if penning so long a piece was pushing it!

HAAPPY BIRTHDAY !! Amazing travaller you are …

Thanks Gemma. It was a very happy day!