No city in Britain rivals Sheffield for ease of access to open country. Yesterday Jasper and I left our home in one of its leafy southwest suburbs for two minutes of walking on terraced roads – Peveril, Carrington, Louth and Stainton – into Bingham Park’s narrow valley: its sides shared by thirties semis, tennis courts and bowling greens, allotments and deciduous woodland falling precipitously on our side, gently on the other, to the Porter; its flow borrowed by a string of mill ponds whose wheels powered – in those early days before cold water from the hills was ousted by super heated steam to make Britain workshop of the world – grindstones from the glacially formed gritstone edges of Stanage and Curbar, stones squatted over by buffer girls in freezing, dust choked sheds lit by oil lamp, meagre coal fire and arcing sparks to bring gleaming finish to blades destined for tables and kitchens the world over.

More at Peak District Millstones

Now the Porter Valley is a green corridor to the Peak, crossed on its way out to open moorland by nothing more jarring than a few scenic lanes.

These short weeks, February to early March, are the most intoxicant – and the most redolent of childhood. Still capable of serving weather as vicious as anything December and January could muster, their lengthening days of snowdrop and snow flurry, birdsong, pussy willow and crocus – with daffodils hard at heel and, soon to come, the speckled eggs of robin and blackbird, frogs joined at the loin – speak to me of fifties austerity in gaberdine hand me down, of numbed toes in wellies too tight (“new ones next winter – money doesn’t grow on trees you know!”) and low curving branches straddled to inch out above icily swirling streams to jeers of roar babby and tha’t freightened, thee, togger on frozen ponds (mums blissfully ignorant) and through it all the naked adrenaline rush of being alive in an adult free outdoors with more energy than you knew what to do with; more days ahead than a nine year old could ever get his head round.

*

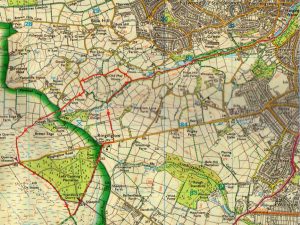

Up the valley to Forge Dam, skirting its left bank to follow the Porter Brook, right where Clough Lane – I love that English has so many words for stream1 – morphs into dirt track. Up Mark Lane past icy puddles, meadows and farms isolated on hillsides spilling down to a Mayfield Valley as pretty as its name, though not at its idyllic best for a good two months yet. From Mark Lane to Foxhall, Foxhall Lane to Harrop Lane to Green House Lane and thence, at the top, where it joins Fulwood Lane on its way to Ringinglow and the road out to Burbage, Stanage and a Hathersage whose churchyard hosts the remains of Little John – and whose vicarage once sheltered a brace of Brontes for the night – we took the stile into the meadow leading to the open moorland and disused, heathed over quarries of Clough Hollow and Brown Edge.

Crossing Ringinglow Road, we took the path southeast, with Lady Canning Plantation to our left, open moor and Ox Stones to our right. Down to the track that crosses Houndskirk Moor from Fox House to Ringinglow, and offers sweeping views of the city. Into Ringinglow with its Round House (hexagonal, truth be told) and dog friendly Norfolk Arms. A few minutes of road to drop down past llama farm and meadow to close the loop at Clough Lane, then retrace our outbound steps down Porter Valley and in for lunch.

Four hours walking. Too cold for loitering but many snap stops. I’d guess eight to ten miles.

Dunritin.

Postscript next day. Before I got home it began to snow. And snow. And snow, for the next thirty-six hours. Early afternoon the next day I retraced my steps. Pictures here.

* * *

Momentarily britain’s greenest city. Thought you might have something to say about capitalism and the cutting of trees, but no…

So much to protest, Stavin. So much, one hardly knows where to start …

Absolutely beautiful – words and pictures

Thanks Catte. Coming from so fine a writer, that’s praise indeed!

You sure had a wonderful walk!

So good I did it again today Dineke, this time in thick snow! Pictures up soon.

A really engaging description of familiar (to me) walks and places with fine photography , including pictures of J!

Loved it!

Thanks Bryan. We had a good walk too, last week. Looking forward to the next.