In part 2 I told of how, in the early to mid nineties:

For the first time in my life, I … began to take seriously the notion of enlightenment in its Eastern as distinct from Cartesian sense.

But more than a quarter-century on I know less than I thought I knew then. Perhaps my earliest ken – that for an Enlightened One, those states many of us have known in fleeting moments of heightened or ‘non dual’ awareness are a place of permanent abode – was as valid as any. It would be exquisitely zen to find myself, after all that effort, back where I started! What of the thousands of hours in meditation, and thousands more in contemplation? What of the hits to career, relationship and family? The prices I paid – as, to varying degree, did those who loved me – were lower than those exacted from others on the same road. But nor were they trifling. So what have I to show for it all?

The spiritual path is a journey from thinking you know to knowing you don’t.

So said a man I once called my teacher, but the above questions stand. And I, though ever fond of the snappy one-liner, have no crisp answer. Have I been short changed? I think not. As I said in part 1, I consider my life blessed. Like Sinatra’s, my regrets1 are too few to mention, and the years of costly enquiry are not among them.

All the same, the paths we tread do so have a knack of bringing us full circle

Ever since the Beatles took off for Rishikesh to sit at the feet of a giggling Maharishi, a small but significant slice of my generation has been drawn by the glittering promise of becoming ‘fully realised’. And where did all that begin? If we really get down to it I can push the start of my own inquiries a lot further back in time than the mid life crisis reported in part 1. At least as far back as my coming home from a local library, aged sixteen, with the Aldous Huxley essay, The Doors of Perception. That essay, its title, like that of Jim Morrison’s band, taken from William Blake’s insight, inspired – nay, compelled – me to take LSD at the earliest possible opportunity.2

Which turned out to be within weeks of my seventeenth birthday. Along with my decision three years later to spend the best part of a year in India, taking acid was a hugely significant turning point: one of no more than half a dozen, tops, I can truly call game changers in the strange set of events it pleases me to call My Life. I am forever in its debt3 but, much as I’d like to pursue this not entirely tangential line of enquiry – and one day I will – it’s time I got back to where I left off in part 2: with an audio tape entitled, Meditation is a metaphor for enlightenment.

*

The man featured on that tape was Andrew Cohen. Though his presence was and I’m sure still is quite remarkable, he never hit the Spiritual Big Time. He’s never attracted millions of followers the way the Maharishi, the Divine Light guy or Osho (aka Baghwan, aka Sri Rajneesh) did. All the more noteworthy then that no fewer than three former students, one of them his mother, have written highly critical books about him. And that a fourth launched the site which made him the first guru, though he will not be the last, to be brought down, though not for long, by the web.

But I’m ahead of myself. Let me offer a cursory introduction to this man, as objective as messy reality ever permits, and consistent with his own accounts of his journey to ‘Awakening’.

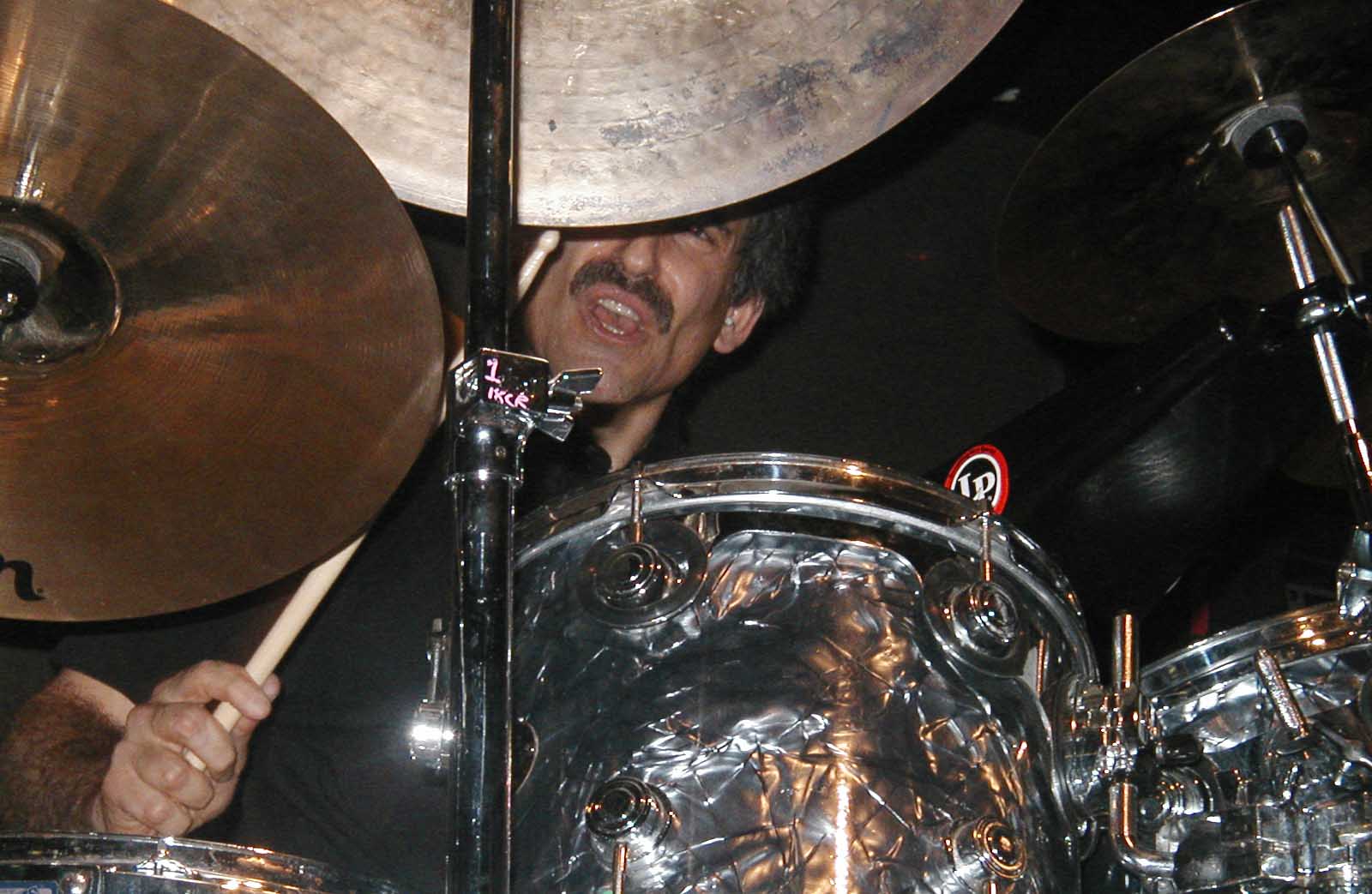

Andrew Cohen was born in 1955 to upper middle class Jewish parents in New York. An unhappy child, unwilling recipient (he says) of the psychoanalysis his mother saw as good for him, in mid teens he had an interlude of deep ‘realisation’; its description a tight fit with the accounts of others – from Juliana of Norwich and earlier to the present day – who report out of time/out of body encounters with life’s essential non duality and immaculate positivity. For young Andrew this was a significant but not Damascene event. He soon reverted to being an insecure and somewhat introverted teenager who, after seeing the Beatles on Ed Sullivan, took to playing the drums. He also took martial arts classes: for some a stepping stone to the ‘spiritual’ scene.

Andrew Cohen at a gig in a downtown bar in Lenox, Massachusetts, April 2002

By early adulthood, Andrew had followed a succession of teachers. Each would disappoint him. Freed by an inheritance from the imperatives of earning a living, he set off for India to immerse himself in the teachings of various gurus, finally settling on the not well known H.W.L Poonja, a man claiming direct lineage to Ramana Maharshi. Upshot? Andrew got ‘enlightened’, Poonja encouraging him to set up as a teacher. This would be 1986. By the early nineties, relations had soured, Andrew declaring that he had ‘surpassed’ his erstwhile teacher.4

Others seemed to agree. Followers, almost all white and middle or upper class (a demographic easily explained by Maslow) set up communities – sangha – in Marin County, Boston, London, Stockholm, Amsterdam and Toronto. At various times there were communities too in New York, Sydney, Copenhagen, Paris and Tel Aviv. Here the most committed lived. In the Marin County community, later to ship (Andrew declaring the California scene tainted by new age frivolity) to the Berkshire Hills of Massachusetts,5 the teacher lived with his students. But his was now the life of an itinerant; his intense schedule taking in the Americas, Europe, India and the Antipodes.

And there I’ll leave his résumé: a lamentably butchered account, but it’ll have to do for now. The man who, aided by the sage he claimed to have outgrown, had achieved ‘enlightenment’6 is the man whose voice I heard when first I played the borrowed audio tape, Meditation is a metaphor for enlightenment.

And what a voice it was. Though his high-pitched giggle, a common trait in those who claim to have seen the light, was and remains a turn-off, I was struck by his eloquence, intelligence and wit. (He could have made it, I’m sure, on the comedy circuits as a stand up of the hard-boiled New York school.) Nor, as I would find over and over in the years to come, did it harm either the man or his message that he is a gifted mimic.

But what was his message? The remainder of this post is my stab at the first half of an answer to that. I’ll keep it brief. So much has been written by and about this man that those wanting more will have no shortage of material, some of it in the short bibliography offered at the end.

*

On that tape, first heard in 1994, a man of rare fluency spoke of the superstitious relationship almost all of us have with thought and feeling. Sadly, though I later bought my own copy, I no longer have it. It’s highly likely I’m conflating some of the things I heard then with what I would subsequently hear in countless other teachings, live or recorded.

(Andrew’s core messages were simple and oft stated but this is not a criticism. Simplicity – and its attendants, integrality and integrity – was dear to his heart and in many but tragically not all ways he exuded the stuff at every turn. In simplicity, he declared and in many ways showed, lie depth and ever unfolding nuance. He would speak with spellbinding clarity about the deepest matters, in words so simple that only later, when trying to sum up, perhaps to a curious friend, what he had said would it dawn on me how ably he had communicated things infinitely subtle. As for his teachings being variations on a few themes, this too was a strength. Another core of his message was an exhortation to Stand in a Place of Not Already Knowing. Already Knowing, he said a zillion times, is the death of inquiry.7 And he showed the truth of this by coming again and again at the same themes, each as a jewel viewed from a new angle, its altered reflections catching us out over and over. See? You thought you Already Knew …)

Not that anachronistic conflation matters much. Andrew’s take on a Right Relationship to Mind did not markedly change in my years with him, and I don’t suppose it has since. On the question of a superstitious relationship to mind, he put it this way:

Walking down the street, you experience a generous and uplifting thought. Unconsciously, you feel good about yourself, concluding yourself a noble soul. A few minutes later you’re assailed by a mean-spirited and base thought. Now you feel a louse! Why? In both cases you drew conclusions about who you are from the content of thoughts (99.99% of which are inconsequential firings of the nervous system) which you think of as (a) ‘yours’ and (b) significant when in reality they are usually neither. To any observer, nothing happened. Nothing happened!

The implications of that assertion, first heard in 1994, continue even now to unfold. Andrew, for all his faults, was right about so many things that matter. But back to that tape.

He spoke of his own confusions and illusions in youth, prior to his ‘awakening’ aged thirty-two. He spoke too of taking hallucinogens (clearly LSD, though in the Q & A – this tape was of a live teaching in NYC – he sensibly dodged an invitation to come out and say so) and of concluding:

Oh boy – this is going to change everything! Once enough people have tasted this, there’ll be no going back …

… then of trying the ‘transcendental meditation’ of the Maharishi, with its quasi-scientific claim that “in cities where 0.01% of the population practices TM, the crime rate decreases.”8

And that didn’t happen either.

The next bit had me smiling, the way his sparkling wit would elicit many smiles to come:

So, despite the fact it doesn’t really achieve anything, I thought we might sit together a while in meditation …

Prior to this he’d spoken of a widespread confusion about meditation; that it is about stilling the mind. In his teaching, he told us, nothing could be further from the truth. For him the point of meditation is to stand in a place where we pay no attention to the play of thought and feeling.

They’re like conversations in adjacent rooms, the kind you decide not to plug into.9

And the point of this? Again I’m paraphrasing recollections:

The goal of enlightenment is a Right Relationship to Mind. But we cannot get there from a Wrong Relationship to Mind, the near universal human condition. It’s too big a hop. We must first cultivate No Relationship to Mind. In meditation we withdraw from the world of karma and consequence, of cause and effect, so as to discover in the most practical way that we are not our minds. If we were, meditation of the kind I advocate would not be possible. And while you may experience profound insights into the nature of reality; while you may go deep into the roaring silence, these things, though of immense value, are not the point. The point is to cultivate no relationship to mind in a place where it is safe to do so. But when you arise from meditation, and the world of causality, temptation and illusion resumes with a vengeance, and no relationship to mind is not possible, what then?

He added, and often, that:

While experiences of profound non duality have great value as signposts, more valuable by far is the cultivation, right there on the meditation cushion, of the warrior stance. The mind may be in the grip of a hurricane but for that hour [the minimum timespan, I would discover, in his teaching] you remain unmoved. And since this distancing from the mind would not be possible if we were our minds, meditation places firmly on the table one of life’s two biggest questions: who am I?

The ideas had me abuzz. I played the tape over and over, savouring the richness not just of the words, or even the delivery, but a totality of experience I had not thought possible within a medium of such narrow bandwidth.

*

When I returned it, Dineke lent me another. For close to two years I availed myself of her well stocked library. Often she suggested I go with her on weekend visits to the London community. I declined. As I did the fewer times when, with Andrew in London, I might experience directly his presence. Though I was now very interested, my life was good. I had my yoga, a fulfilling job, my two children and a blooming love life. (I also had memories of an earlier, though far milder cult: the Trotskyist sect, Workers Power.) Even at this stage I sensed that the totality of his teachings would threaten these things. That they might well, given my lifelong tendencies to leap before I look, consume me in flames – just as he was in fact promising they would.

When finally I did see Andrew teach, early summer of 1996, the effects would be explosive.

* * *

Bibliography

And if you said jump in the river I would

Because it would probably be a good idea

You’re not supposed to be here at all now

It’s all been a gorgeous mistake

Sick one or clean one

The best one that God ever made

Sinead O’Connor

Andrew has written (often with uncredited literary input from close students) several books. I’d choose Freedom Has No History, a more coherent text than his beloved, Enlightenment is a Secret. See also In Defense of the Guru Principle for its characteristically robust assertion of the authority of the ‘spiritual teacher’. A word of warning. That authority is premised on an assumed infallibility which stands up neither to evidential scrutiny nor common sense. And as Alstad and Kramer, authors of the Guru Papers (see below) point out, a guru-chela relationship familiar in the east – hence less cut-off on the one hand from wider society, on the other from spiritual traditions and hierarchies to which it is in theory answerable – poses greater dangers when transplanted in the West. All the more so when fused with Manichaean ideologies (see the marker placed in footnote 7).

All of Andrew’s former students turned critics merit a read. They are Luna Tarlo (The Mother of God), Andre van der Braak (Enlightenment Blues) and William Yenner (American Guru). Do not neglect the website launched by Hal Blacker: WHAT enlightenment??! I say this not just because it is the most easily accessed, and houses not one but many voices. It also has the distinction that, more than any other factor, it brought about Andrew Cohen’s downfall as a teacher in the sense we knew him

What struck me after leaving Andrew Cohen, and six months later beginning to read critical accounts – his mother’s book, then those by escapees from other gurus – was their uncanny similarity. It was as if, in reading of the Maharishi, or Osho, or Scientology, I was reading about Andrew himself. I therefore recommend two Netflix offerings. Wild Wild Country documents in six episodes Osho’s move from India to Oregon. What ensued is staggering. As with what went down in Andrew’s communities, you really couldn’t make it up! Yet all we are witnessing is the playing out of an entirely logical process. Friends who’ve never been near a spiritual community were as gripped by this account as I was.

The other Netflix offering, more recent, is The Vow. This too, a nine parter, I found riveting from start to finish. Unlike Andrew’s, Osho’s and many other cults, Keith Raniere’s NXIVM (“nexim”) group was less ‘spiritual’ than ‘self improvement’ – though in the new age West, the latter often cherry picks the former for ideas. In any case, the same deadly dynamics are at work.

The fact of such commonality leads me to my last and, for those indifferent to Andrew Cohen, biggest recommend. More than any other resource – certainly more than the offerings, usually superficial and too often by armchair experts with masters degrees in psychology, an eye for the market and few other credentials – The Guru Papers explores the science of the guru-chela relationship. This is all the more remarkable when its interest in the guru phenomenon per se is incidental. Its primary focus is the dynamics of interpersonal power, not just in the guru-chela relationship but also in sexual and workplace relationships. Since scientists find it most useful to study things in their purest forms, authors Diane Alstad and Joel Kramer scrutinise the guru phenomenon because, short of situations where coercion is backed by physical force, few more distilled forms of interpersonal power exist.

*

- On regret, I concur with something I heard in a time management talk given, aptly enough, by a man who knew his death from pancreatic cancer was three months away at most. “It’s not the silly, embarrassing things you did”, he insisted, “that you’ll regret. It’s the things you longed to do but didn’t; the times you sold yourself short.” So true. As a keen amateur photographer I’ve long been aware that, given basic competence in technical aspects of the craft, the real threats to excellence come from failures to act in the face of fear or laziness. (Neither being quite what it seems.) This is a truth by no means confined to photography.

- Huxley’s explorations were with mescaline, from the peyote cactus of Mexico and the south-west of the USA. Its effects when ingested in quantity bear striking resemblance to those of LSD. (As do those of the psilocybin mushroom, abundant on the moorland ringing steel city. By the time this became common knowledge, in the late seventies, I’d hung up my tripping boots.)

- I’ve long held the view that through the explosion in the late sixties and seventies of psychedelia, and interest in ‘alternative’ ways of viewing and being in the world, LSD touched everyone of my generation, whether or not they tried it. On a more personal note, while we all knew ‘heads’ who tripped at the drop of a hat, with no more sense of consequence than others might bring to toking a joint or sipping a beer, I looked on acid, the most powerful state changer I’ve experienced before or since, with respect. (The one exception, the night I took it because I was bored, it punished my irreverence in no uncertain terms. Even then, however, it taught me a valuable and lifelong lesson: that boredom is never what it seems. Though experienced as a mildly unpleasant lack of stimulus, ennui is best understood as a dam holding darker currents, nothing about them mild, at bay.) I allowed at least three months between trips, each of them lasting eight to twelve hours at full strength, with flashbacks and other follow-ups for a week or more after. Since I stopped at twenty-five, believing it had served its purpose and had little more to teach me, I doubt I took LSD more than a dozen times. As for those of my acquaintance who dropped acid like kiddies in a sweet shop, a horrifyingly high number never saw middle age. Not, I stress, due to acid, even in excess, but because they brought the same nihilistic confusions to less potently transformative but more dangerous drugs – and, damaged souls that they were, to their relationship with life itself.

- Andrew’s mother, a remarkable woman with whom I used to exchange emails and the occasional phone call, shed a little light on this. By the time of the 1992 rift with Poonja – see also this account by a former student – she’d become her son’s fiercest critic. She would soon write a book, Mother of God, and at the time was gathering material. As word reached New York of discord in far off Rishikesh she asked an acquaintance, an Indian she calls an anti-guru expert: what will my son do if Poonja disowns him? Quick as a flash, she told me, her man had replied: ‘he will claim to have surpassed his former master’. What made him so sure? There is a science of guruhood, explored in The Guru Papers. Though I drifted from her as my fascination with her son waned, I remain indebted to Luna Tarlo for many things. One being her steering me towards that invaluable resource.

- The Massachusetts community at Foxhollow came closest to the sangha ideal of a self contained environment. Most students in that breathtakingly idyllic setting lived and worked ‘on the job’. By contrast the other communities, with London the biggest after Foxhollow, comprised a Centre where teachings, meditation and other practices took place. Students, most of whom had day jobs in the ordinary world, lived communally but in small units: typically sharing flats within walking distance of the Centre.

- As best I recall, Andrew never directly said, “I am enlightened”. He was often asked the question point blank, a few times in my presence, but knocked it back every time: “you must decide for yourself”. But circumstantial evidence that he does indeed deem himself ‘enlightened’ is overwhelming. “I wouldn’t have the audacity”, he would say, “to do what I do if I didn’t think I had something extraordinary to offer”. Add to this the titles and content of his books – try Enlightenment is a Secret – and we are left in no doubt on the matter. This is as good a place as any to mark my scepticism over a widely held perception that ‘enlightenment’ is a Boolean: that you is enlightened or you isn’t; end of. From my own experiences I am in no doubt that Andrew Cohen had access, on a highly stabilised basis, to rare depth of insight into the human condition and some aspects of the nature of consciousness. Whether this access was 24/7 and highly generalisable is more debatable. I heard him peddle poppycock, most of all on political matters about which he knew nothing, cared less and consequently – this too is a science – sided unwittingly with evil. Which brings me to a related issue. Though coy about his own state of attainment, Andrew said many times that the ‘enlightened’ being, having burnt off all karma and tamed the ego, cannot make serious mistakes. Given that Andrew saw himself as not only ‘enlightened’ but on the uppermost rung of its ladder (not such a Boolean then!) a wealth of evidence shows that belief to have been deluded; recklessly so.

- In this context, Already Knowing is egoic attachment. In Andrew’s teaching, as in other though not all Eastern flavoured teachings, Ego, its assumed forms endlessly varied, plays the role Satan does in the Abrahamic faiths. In Bible and Koran, Satan wages war – deploying tank battalions here, lawyerly sophistry there – on God. Here, Ego, antithesis of non duality, uses similar tools to wage war on Truth and Enlightenment. It’s not that Freudian understandings of ego as a self organising principle are wrong. Just that, as with materialism, discussed in part 2, the same term denotes two very different concepts. In its ‘spiritual’ sense of arrogant self importance, a self organising principle is the least of its agendas. Ego, I heard Andrew say, can’t bear our being happy. The radical simplicity of happiness leaves no room, no nooks and crannies of complexity, for Ego to thrive. Indeed, in this sense of the word a cornered Ego may even place its host at great physical risk to avoid its own demise or subjugation.

- Whether the TM claim, in the 70s as ubiquitous as Kilroy, was 0.1% or 0.001% scarcely matters. It is so unfalsifiable as to be worthless, scientifically speaking. This would not, of course, make TM itself worthless. I never tried it, so can’t by any criterion comment on its value.

- See part 4. Days after writing about “conversations in the next room”, I remembered that this remark came two years later, the day I first saw Andrew in the flesh.

15 Replies to “How I joined a cult. Part 3: Enlightenment”