This morning on BBC Radio 4’s Thought for the Day, the Rev Giles Fraser gave a simplistic tour of the selfishness v altruism debate. He didn’t follow the many who rubbish Dawkins without reading his most important work; indeed, he quoted the man aptly and with approval. Nor do I dispute his conclusion that altruism is part of our make up. The me/you/we calculations are certainly more nuanced and complex than he gave credit for – witness decades of research on Game Theory – but, fair’s fair, there’s only so much you can do in a two minute slot.

No, my gripe is with his classic error of conflating gene and organism, jumping indiscriminately between genetic and human imperative as if the two were interchangeable. To posit a ‘selfish gene’ is neither to advocate ‘every man for himself’ nor to describe the human condition. It is to describe laws of evolution via random genetic mutation and natural selection; laws massively corroborated by later findings using technologies unavailable to Darwin.

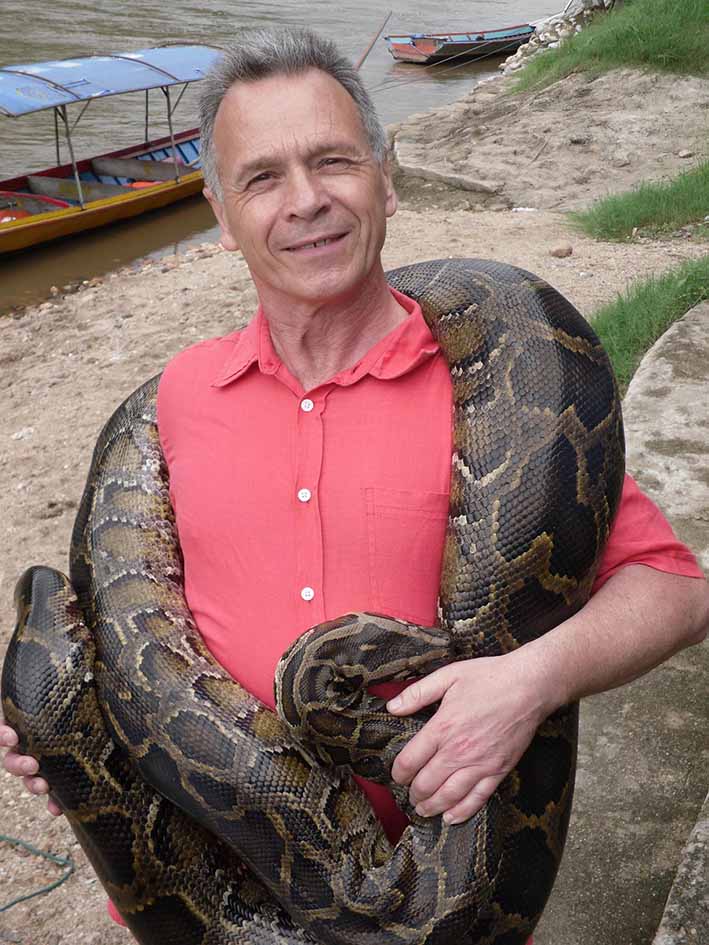

Speaking of genes, I offer this 700 worder on snakes, fear and self awareness. It’s one of many I never got round to sending from Vietnam in March.

*

Scared of snakes?

In my social science undergraduate days a fellow student set out in his final year dissertation to discover “why so many people have an irrational fear of snakes”. He had a bee in his bonnet, you see, having worked the summer at a zoo. His starting point, that the vast majority of snakes pose no threat to humans, was sound but he drew from it an unexamined conclusion – fear of them is therefore irrational – far less so.

There are those who link snake ‘phobia’ to the biblical account of the Fall. Even Kipling, who really should have known better, writes in Kim of “the white man’s horror of the serpent” but in my travels I’ve seen Hindu and Buddhist, African and Asian, display the same aversion. More telling yet, other primates show distress when confronted by snakes. What’s going on?

I look to evolution. Instinctive fear of snakes confers a tiny advantage, and tiny advantages are what the natural selection of random genetic mutations is all about. So why, Genesis blamers object, don’t tigers evoke the same visceral response? The difference, surely, is that it’s obvious tigers can do us in. They are big and heavy. They have fearsome teeth and claws. Most snakes by contrast are small, light and without visible weapon. A few, however, can pose a grave and sudden threat. As with other matters too urgent to be left to conscious reasoning, we need a mechanism to bypass our admirably capable but pedestrian higher brain processes. Is it really so irrational to be repelled by snakes? Should we really lose vital seconds establishing ‘rationally’, and likely as not in low visibility, whether that neck-stripe is the sage green of the harmless mud snake, or olive green of the near identical but deadly sand viper?

Fear of snakes is no more irrational than fear of heights. The visual cliff experiment with babies suggests this too is innate and, we may conclude, evolutionarily useful. But climbers and other thrill seekers learn to transcend that fear – or to savour its frisson – and this points us to something uniquely human and relevant here. Apes fear snakes; horses too, as thrown riders have found to their cost. But with ape or horse that’s all there is to it. Neither can of its own accord overcome that instinct whereas we, given an incentive, can: not just because we are more intelligent but because we are self aware. We can stand back from the play of our minds to judge a fear or desire, however ‘natural’, to be holding us back from something we want more. (In Voyages of Sinbad, recall, snakes are guardians of fabulous jewels, a time honoured mythic association.)

Early explorers assuredly felt homesick: that too is useful; keeping us on our own turf where we are by and large safer. But homesickness did not stop them, and the difference is not that human fear can be overridden – we can train animals to overcome fear – but that we can do it by our own volition. Willpower presupposes self awareness: an asset as critical to our ascendance, perhaps, as abstract reasoning, language and opposing thumb. Our ancestors feared heights, fire, alien landscapes and much besides but the more intrepid and curious faced down the movement of their own minds and led us onwards and upwards. 1

They had their reasons, mind. It is not in our nature to exercise will without cause, and this takes us back to the topic in hand. Some fears are highly disruptive of everyday life. I know someone whose father had foliphobia. I know another with koumpounophobia (Apple’s Steve Jobs had it too). Since leaves and buttons are daily inevitabilities, we can agree these aversions must pose logistical problems far from trifling. Snakes by contrast are seldom encountered. Even in hot climates they do their best to stay out of our way. Given this, and the fact our days are numbered, we may choose to do other things with our time than master an instinct seldom needed in modern life, to be sure, but by the same token no great hindrance either.

That seems eminently rational to me

* * *