Syria .. Putin .. Brexit .. Corbyn .. climate change .. Trump. What have they in common? All are issues on which most of us have opinions we imagine we arrived at ourselves. But didn’t Asch and Milgram show how exaggerated a sense we have of our independence of thought?

Here in edited form are the opening paragraphs of a Media Lens piece today. I recommend reading it in full.

When a Saddam, Gaddafi, Assad or Trump are declared the ‘New Hitler’, we learn only that they are enemies of the establishment. It means the On button has been pressed for maximal demonisation, leaving no room for public doubt.

The rationale is understood by the PR community. Phil Lesley, author of a handbook on PR, explained the strategy for obstructing action on environmental issues:

People do not favour action on a non-alarming situation when arguments seem balanced on both sides. Nurturing doubt by saying things are not clear-cut is usually all that is necessary. (Lesley, ‘Coping with Opposition Groups,’ Public Relations Review 18, 1992, p.331)

Conversely, when action is required, the issue must be presented as one-sided, clear-cut, black-and-white.

This doesn’t mean Saddam wasn’t a tyrant, or Trump isn’t a threat to uncivilisation; it means establishment enemies are called ‘New Hitlers’ for reasons that have little or nothing to do with any threat they might pose.

In Trump’s case, the public was not being softened up for invasion, bombing and murder, though his liberal opponents have often ‘joked’, unaware of the irony, about assaulting and assassinating him … full piece here

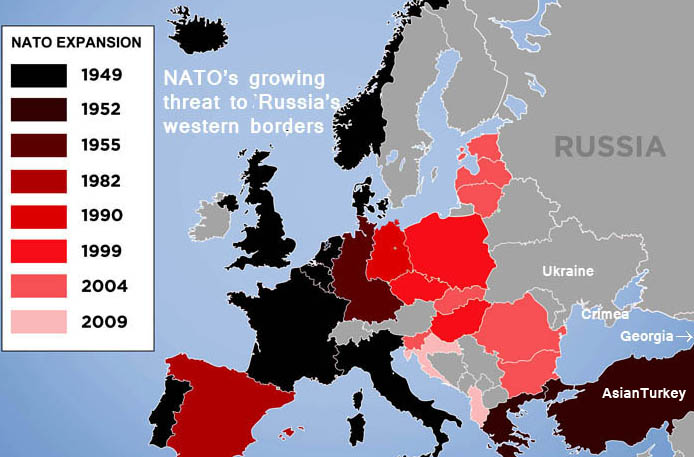

An implication that last paragraph but one hints at is the way cognitive dissonance can propel those of us who resist such demonisations into mirror image defence of the demonised. Can we defend Putin’s refusal to be cowed, by a western aggression pushing NATO to Russia’s borders, without denying his homophobia? I think so, but it’s a struggle. A struggle against a centre left unable to look beyond identity politics to the bigger picture of US-led imperialism determined to maintain supremacy in the face of economic decline. And a struggle against those at the other end of the spectrum who defend the indefensible and/or deny the undeniable when a simpler response is also more incisive: OK, so he’s not to liberal tastes – you think that’s why NATO hates him?

Similarly, while it’s hard to get the HRC-as-lesser-evil school to answer the question – what kind of moral universe are we in that Trump’s offensiveness outweighs waging war for profit and political ambition? – it may prove no easier getting HRC haters (and by the way some are misogynistic*) to concede that Trump may step down the threat to Russia, if America’s ruling class allows it, only to step up the threat to China.

Cognitive dissonance, and a love of the simple that can too easily take us across the line into the simplistic, make this hard enough. It gets even harder when allegations we might concede, within an overall stance of critical defence of the demonised, may well be untrue. Charges of Putin ordering the Litvinenko and Politkovskaya murders fall into this category, as do claims of Pussy Riot as freedom fighters. Likewise some of the charges against Assad. (Though there’s ample evidence of the fake independence of groups – Human Rights Watch, White Helmets and Syrian Observatory for Human Rights spring to mind – claiming neutrality and routinely drawn on by mainstream media as impeccable sources.)

Attitudes to unsavoury or seemingly unsavoury targets of imperialism have always divided the left, especially where those targeted are fighting the “home” state. (Witness the toxic divisions within Britain’s far left over the Provisional IRA in the seventies and eighties. While we’re at it, let’s salute the courage of those Israelis who stand in solidarity with the Palestinians). Surely the way to go is one of commitment to small truths paired with commitment to the bigger ones. This doesn’t magic away the difficulties, far from it, but does offer a principled approach. Here’s an example of what I mean, posted months ago in a piece on privatisation:

Granted, the [privatisation] narrative is now different. Instead of inefficient services or irresponsible governance an empire of evil or blood soaked Middle Eastern or Balkan regime must be demonised. Such allegations may hold a grain of truth, a great deal of truth, or be baseless. (Though even where there is truth a heavy responsibility lies often as not with those making the allegations, as in the vilification of Saddam by the very interests that had for so long sold arms to him.)

But whether or not the demonising of distant regimes has substance, and whether or not it is hypocritical, are secondary questions. In no case – cold war on the USSR, devastation of Yugoslavia, violent destabilisation in the middle east – have cited casus belli been the real drivers of US led hostility. In each example, of regimes practising some degree of state capitalism, we can infer true motive from outcomes: a transfer of wealth from public to private hands …

I dare say the good Phil Lesley, as cited by Media Lens, would advise in no uncertain terms that the kind of nuance I refer to simply won’t fly. Once a message is put out for mass consumption, he would surely say, it must be stripped of all ifs, buts and on the other hands – except where, as he so clinically puts it, obfuscation is the aim. He’s right too, and that’s why I’m assailed by doubt and pessimism on a near daily (and nightly) basis. But it’s also why all we are left with – and it’s no small thing – is our commitment to truth when that can require not only courage and independence, intellectual effort too, but also a deepened sense of enlightened self interest.

Damn! I hate writing posts that wind up sounding like BBC Radio 4’s Thought for the Day …