The rentier nature of British capital is revealed by this IPPR report: “Corporate investment has fallen below the rate of depreciation – meaning that our capital stock is falling – and investment in research and development (R&D) is lower than in our major competitors. Among the causes are a banking system that is not sufficiently focused on lending for business growth, and the increasing short-termism of our financial and corporate sector. Under pressure from equity markets increasingly focused on short-term returns, businesses are distributing an increasing proportion of their earnings to their shareholders rather than investing them for the future.”

Michael Roberts, below.

Tomorrow Britain will with little enthusiasm – and in very much lower numbers, proportionally speaking, than those which in March re-elected Mr Putin in Russia – put its five-year collective pencil to the tick-box of illusory choice in such a way as to eject TweedleTory from office, and usher in TweedleTorylite.

But what kind of state is this Britain? And what kind of state is it in?

Sometimes, as I opined yesterday, we can let facts do the talking. Not always, to be sure. In fact not even often when it comes to big data on important things. More commonly the facts cry out for interpretation. But as if to prove that yesterday’s case study of China’s annihilation of the competition in global electric car sales was no fluke, here’s one closer to the birthplace of steel city scribblings.

Michael Roberts describes himself as a Marxist economist. Which might seem odd given how little he’s written of Gaza or Ukraine, with not a whole lot more on the economic war the West has declared on China.

That’s not a criticism by the way. Some Marxists are happiest at the unglamorous end of class struggle. They beaver away like Bob Cratchit in Scrooge’s counting house, every once in a while surfacing with the quarterly reckoning. And what a reckoning we have here, in this the Week Of Electoral Choice! Remember Bertie Wooster’s instructions to his gentleman’s gentleman?

Brandy and soda, Jeeves – and go easy on the soda!

Well Michael Roberts has shimmered in with the stats-man’s equivalent: a very large glass of fact and comment that goes easy on the comment.

Broken Britain

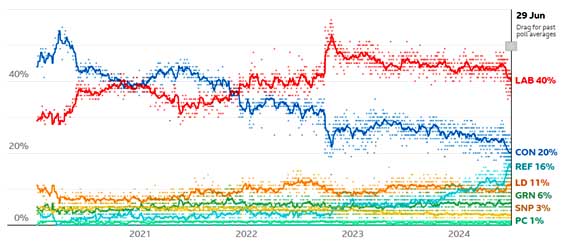

UK citizens vote in a general election on 4 July. The opinion polls currently forecast that the incumbent Conservative party will be heavily defeated after 14 years in government. The opposition Labour party is expected to gain a majority of over 250 seats, a record landslide, with the Conservatives getting less than 100 seats.

But ahead of the election, 75% of Britons have a negative view of politics in Britain. And Labour and the Conservatives are set to record their lowest combined share of the vote in a century. Instead, smaller parties such as Reform, the Liberal Democrats and the Greens have all made advances.

This result is a consequence of the disastrous decline in the British economy and living standards for most Britons alongside a decimation of public services and welfare. British capital is broken.

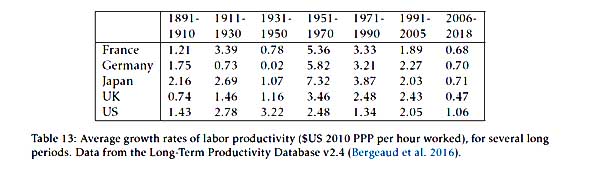

The UK economy is now the ninth-largest world economy in terms of output at prices adjusted for purchasing power and sixth when output is calculated at exchange rates. But British imperialism has been in steady decline since the end of WW1, giving way to US imperialism as the hegemonic power. And after WW2, the UK increasingly became a subservient ‘junior partner’ to America. The relative decline in the UK economy is revealed by its long-term fall in productivity growth compared to other imperialist economies, particularly in the 21st century.

In his recent book, Vassal State – how America runs Britain, Angus Hanton shows the dominant role that US companies and finance play in owning and controlling large sections of what remains of British industries. This US takeover was accepted and even encouraged by successive British governments from Tory Thatcher to Labour’s Blair.

Hanton shows that in Thatcher’s second full year in office, 1981, only 3.6 per cent of UK shares were owned overseas. By 2020 that number was more than 56 per cent. Of all the assets held by US corporations in Europe, over half of them are in the UK. US corporations have more employees in the UK than the number they have in Germany, France, Italy, Portugal and Sweden combined. The largest US companies sell more than $700 billion of goods and services to the UK, which amounts to over a quarter of the UK’s total GDP.

Almost 1.5 million UK workers are officially dependent on large US employers; if we count the indirect employees, such as Uber drivers and Amazon’s agency workers, at least 2 million UK workers have ultimate bosses in the US (6–7 per cent of the UK workforce). By 2020 there were 1,256 US multinationals in the UK – based on the IRS definition of a multinational as an enterprise with more than $850 million of foreign sales.

From the 1980s, Britain has increasingly become what we could call a ‘rentier economy’, ending most of its manufacturing base and relying mostly on the City of London financial sector and accompanying business services, providing a conduit for the redistribution of capital from the Middle East oil sheikhs, Russian oligarchs, Indian entrepreneurs and American techs.

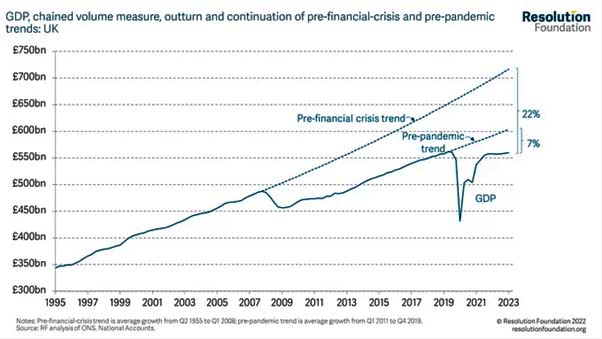

Throughout this period, British capitalism declined relative to its peers among the G7 economies and other larger European states. But particularly after the Great Recession, and after the decision to leave the EU and the COVID pandemics, the British economy went into a downward spiral that so far it has not been able to stop. Real GDP growth is still more than 20% below its pre-2008 trend – although that fallback applies to all G7 economies, if at a lesser rate.

The UK economy was the hardest hit of the top G7 economies in the year of the COVID. Real GDP fell 9.9%, which the then finance minister and now PM Rishi Sunak admitted was the worst contraction in national income in 300 years! The economic think-tank, the Resolution Foundation, reckons that the UK economy may not have had “a technical recession but we are experiencing the weakest growth for 65 years outside of one (a recession).”

What is also forgotten is that population growth is at its fastest rate in a century (three-quarters driven by immigration of 6m people since 2010). If population growth is excluded, the UK has barely seen any economic growth, with GDP per person only just above the level of 2007 and real consumer purchasing power still lower than in 2007.

Indeed, productivity growth (that’s output per worker per hour) has been terrible. Productivity has slowed to under 1% a year. Before the 2008-09 economic crisis, Britain’s output per hour worked grew steadily at an annual pace of 2.2% a year. In the decade since 2007, that rate has dropped to 0.2%. If the previous trend had continued, the UK’s national income would be 20% higher than it is today …

… And it is estimated that the post-Brexit trading relationship between the UK and EU, as set out in the ‘Trade and Cooperation Agreement’ (TCA) that came into effect on 1 January 2021, will reduce long-run productivity by 4 per cent relative to remaining in the EU …

… In effect, UK productivity has flat-lined for a decade. So now productivity levels are as much as one-third below those in the US, Germany and France: “the average French worker achieves by Thursday lunchtime what the average British worker achieves only by close of business on a Friday.” Indeed, excluding London the UK’s average productivity level is below that of the poorest state in the US, Mississippi.

The productivity gap between the top- and bottom-performing companies is materially larger in the UK than in France, Germany or the US. This productivity gap has also widened by far more since the crisis – around 2-3 times more – in the UK than elsewhere. This long and lengthening tail of ‘stationary’ companies explains why the UK has a one-third productivity gap with international competitors and a one-fifth productivity gap relative to the past.

Why is productivity growth so poor, especially among the key big British multi-nationals?

Correct us if you dare. Productivity is regarded by Marxists as a measure of exploitation. Not necessarily in the simplistically pejorative sense understood by vulgar socialists. At the heart of Britain’s terrible productivity is neither “too short” a working day nor “greedy workers”, but lack of the capital investment required by modern manufacturing to keep up in world markets.

(This too is touched on in the previous post, but as a general phenomenon across the West, whereas factors intrinsic and extrinsic 1 single out the UK for basket case status.)

How does this bleak picture play out in the issues which most matter to ordinary Britons? Issues no less marginalised, as accountant and tax specialist Richard Murphy recently noted, by Keir Starmer’s eviscerated Labour than by Rishi Sunak’s soon to be electorally vapourised Conservatives? I speak of the NHS, of millions below the breadline in the gig economy, of decaying physical and social infrastructures, of a year on year weakening of the rule of law and much besides.

Do continue reading Michael Roberts’ grimly compelling but irrefutably fact based assessment of the state we’re in.

* * *

- Intrinsic drivers of Britain’s economic decline derive from its status as the world’s first industrial capitalism; aging infrastructure and the playing out of capitalism’s tendency to falling rates of profit. Extrinsic factors feature Britain’s rentiers taking it further and faster down the road of financialisation and de-industrialisation than the West at large. As for an intellectual legacy of laissez-faire – effect and cause of the dominance of finance over industrial capital – I deem that a hybrid of the two. Finally, and taking nothing away from the corruption of an EU whose own chickens are coming home to roost – note to self: post required on the plight of the Extreme Centre – a car-crash Brexit has exacerbated all these factors. As have the crippling costs of the West’s proxy war in Ukraine.

The key question – which will hopefully be tackled in the promised follow up article – is whether or not the policies of what passes for the Labour Party these days will seriously address these structural issues or merely continue to elevate those forces responsible for this situation as the only “viable” and “credible” way of doing anything and everything?

I think we already know the answer to that one!

If you think the prospectus in the article is bad, try some of this:

https[colon slash slash]thehonestsorcerer.substack.com/p/2025-a-civilizational-tipping-point

and if that doesn’t convince, try these:

https[colon slash slash]dothemath.ucsd.edu/2024/04/distilled-disintegration/

https[colon slash slash]www.artberman.com/blog/radical-acceptance-of-the-human-predicament/

http[colon slash slash]resourceinsights.blogspot.com/2024/04/the-short-circuiting-of-societal.html?m=1

(addresses altered to get round ‘spam’ filter)

Just spent several irksome minutes converting these links, Jams. They look interesting, though offered at a very different level of analysis than Michael Roberts’.

Did you try to enter them as URLs and have them rebuffed? If so I do need to check my Spam settings in WordPress.

Duh – just remembered. You’re one of three trusted commentators who, despite my settings allowing your comments to proceed immediately to publication, are inexplicably held back for moderation. The other two also have names beginning “O”-apostrophe. I’ve tried several times to get to the bottom of this anti-Irish conspiracy, all to no avail.

Meanwhile, rest assured that URLs are permitted, and the count is certainly higher than four.