The Economist today, September 27 2024, highlighting added

In this week’s contents round up, Economist Editor-in-chief Zanny Minton Beddoes writes:

This month I spent a week in Ukraine. Together with my expert colleagues, Oliver Carroll and Arkady Ostrovsky, and our podcast producer, Heidi Pett, we criss-crossed the country from near the front lines in the east to Kharkiv, Dnipro and Odessa. We went to places that I had hitherto known only as marks on The Economist’s frequent maps: Kramatorsk, Zaporizhia, Pavlohrad. I wanted to see for myself how Ukraine is faring. We spoke to politicians, military commanders and business leaders, as well as to ordinary soldiers and civilians fighting, and living, in the 32nd month of Ukraine’s full-scale war. I then spent a few days with colleagues in Washington, to get a feel for where American policy towards Ukraine is heading.

The result is our cover story this week, and an hour-long episode of the Weekend Intelligence podcast that will air on September 28th. They are a sobering read and listen. It is crunch time in Ukraine, with its forces under pressure, winter approaching and the future of American support uncertain. We argue that both President Volodymyr Zelensky and his Western backers urgently need to change course. Greater honesty is needed about what is feasible militarily and the nature of the support Ukraine needs.

Here’s that cover story, with my comments.

If Ukraine and its Western backers are to win, they must first have the courage to admit that they are losing. In the past two years Russia and Ukraine have fought a costly war of attrition. That is unsustainable. When Volodymyr Zelensky travelled to America to see President Joe Biden this week, he brought a “plan for victory”, expected to contain a fresh call for arms and money. In fact, Ukraine needs something far more ambitious: an urgent change of course.

This opener makes two long overdue concessions. One is that, as this site and others outside the mainstream have said for two years, the Ukraine is losing the war its hapless peoples have been dragged into – even if The Economist has yet to allow, if ever it does, that the causes of that war reside in (a) reckless NATO expansion, (b) the US coup of 2014, (c) a frightened puppet leader 1 whose mandate expired four months ago, (d) a US-led West determined to fight Russia down to the last Ukrainian.

The paragraph’s other concession – recognised as such by those who have not forgotten that The Economist has not been saying this all along – is that this is indeed a war of attrition. That’s no small thing when the Westside story has from day one told of territorial conquest by an evil dictator; this being the Official Narrative relayed by systemically corrupt media which, while they may – indeed, for credibility and market share, must – make a show of challenging power on non-critical matters, always fall into line via power-serving propaganda blitzes on matters as crucial to its agendas as war. Even proxy ones.

Selling this war as resisting the land grab of a new Hitler 2 was vital for narrative purposes, but the West, including generals with no experience of fighting a peer adversary, made the cardinal mistake of falling for its own spin. One reason it thought its proxy was winning was the glacial pace of Russia’s advance. Such meagre gains, it told itself, showed the weakness of RF forces. 3

A measure of Ukraine’s declining fortunes is Russia’s advance in the east, particularly around the city of Pokrovsk. So far, it is slow and costly. Recent estimates of Russian losses run at about 1,200 killed and wounded a day, on top of the total of 500,000. But Ukraine, with a fifth as many people as Russia, is hurting too. Its lines could crumble before Russia’s war effort is exhausted.

Russian forces are undoubtedly taking losses. However:

- Vladimir Putin’s recent re-election (by a share of the vote vastly exceeding Keir Starmer’s in Britain) speaks to a people in no doubt as to the existential nature of its fight.

- Russia’s superiority in materiel, not just over Ukraine but the West at large, keeps those losses to a minimum. (All the more so given the patience shown, throughout the conflict and to the exasperation of Kremlin hawks, by her political and military leaders. 4 ) Due to these realities …

- … claims of losses at 1200 a day, added to half a million already incurred, are worthless. That The Economist can parrot them without offering evidence or even naming a source goes beyond bad journalism. It speaks of bad faith.

Ukraine is also struggling off the battlefield. Russia has destroyed so much of the power grid that Ukrainians will face the freezing winter with daily blackouts of up to 16 hours. People are tired of war. The army is struggling to mobilise and train enough troops to hold the line, let alone retake territory. There is a growing gap between the total victory many Ukrainians say they want, and their willingness or ability to fight for it.

Largely true, as we can ascertain both from triangulating sources and by its being what lawyers call a “statement against interest”. But this talk, again unattributed, of “the total victory many Ukrainians say they want”, sidesteps the truth of a people not free to speak out in a country – even before being plunged into this needless war by Victoria Nuland in 2014 – famously corrupt and fear-driven. For Ukrainians to openly oppose the war would be not so much courageous as foolhardy. Ergo, to speak of a gap between what they say they want, and how willing they are to fight for it, is to disrespect those The Economist purports to champion.

Abroad, fatigue is setting in. The hard right in Germany and France argue that supporting Ukraine is a waste of money. Donald Trump could well become president of the United States. He is capable of anything, but his words suggest that he wants to sell out Ukraine to Russia’s president, Vladimir Putin.

War is peace for (neo) liberals who depict opposition, fast gathering steam as Europe awakens to the extent of its leaders’ betrayal, to the war as a thing of the “hard right”. 5

If Mr Zelensky continues to defy reality by insisting that Ukraine’s army can take back all the land Russia has stolen since 2014, he will drive away Ukraine’s backers and further divide Ukrainian society. Whether or not Mr Trump wins in November, the only hope of keeping American and European support and uniting Ukrainians is for a new approach that starts with leaders stating honestly what victory means.

Talk of land stolen, besides distorting the complex and fluid history of a country whose name means “Borderland”, rides roughshod over the truth that the peoples of Crimea, Donetz and Luhansk have shown an overwhelming preference for absorption into Russia. 6

As The Economist has long argued, Mr Putin attacked Ukraine not for its territory, but to stop it becoming a prosperous, Western-leaning democracy. Ukraine’s partners need to get Mr Zelensky to persuade his people that this remains the most important prize in this war.

First, wouldn’t the argument that Ukraine is fighting for democratic values be (slightly) more convincing from a ‘leader’ whose presidency had not ended on May 20? And had the Ukraine constitution not stipulated that the Speaker in the Rada must serve as interim president?

Second, I wish The Economist would say how long it has argued that “Mr Putin attacked Ukraine not for its territory”. I follow it passably often and this is news to me! That’s a minor carp, mind, when (third) set against another claim freshly minted. Forget this:

Forget too the many other grounds for saying Russia was provoked with malice aforethought. Now all is made clear by the laser-like insight and profound sagacity on offer at The Economist. The bloodbath which is today’s Ukraine has nothing to do with Washington designs as helpfully laid out in its Pentagon commissioned 2019 Rand Report, Extending Russia, and everything to do with a tyrant bent, like a cartoon villain for whom evildoing is its own reward, on thwarting democracy in Kiev!

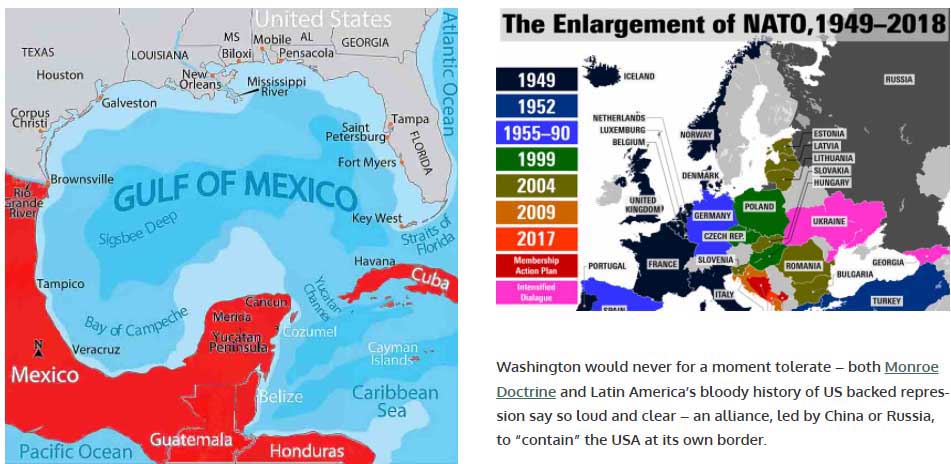

Simples. But here endeth the sarcasm. What follows is Alice in Wonderland logic. The way to end the war, argues The Economist, is to double down on what started it. In short, make not the slightest of nods to the truth that Russians who six months ago re-elected their president by a landslide 7 had every reason to fear a next-door state – conduit for every Western invasion of their homeland, from Charles XII of Sweden through Bonaparte to Hitler – entering a US-led alliance predicated on their encirclement.

However much Mr Zelensky wants to drive Russia from all Ukraine, including Crimea, he does not have the men or arms to do it. Neither he nor the West should recognise Russia’s bogus claim to the occupied territories; rather, they should retain reunification as an aspiration.

In return for Mr Zelensky embracing this grim truth, Western leaders need to make his overriding war aim credible by ensuring that Ukraine has the military capacity and security guarantees it needs. If Ukraine can convincingly deny Russia any prospect of advancing further on the battlefield, it will be able to demonstrate the futility of further big offensives. Whether or not a formal peace deal is signed, that is the only way to wind down the fighting and ensure the security on which Ukraine’s prosperity and democracy will ultimately rest.

This will require greater supplies of the weaponry Mr Zelensky is asking for. Ukraine needs long-range missiles that can hit military targets deep in Russia and air defences to protect its infrastructure. Crucially, it also needs to make its own weapons. Today, the country’s arms industry has orders worth $7bn, only about a third of its potential capacity. Weapons firms from America and some European countries have been stepping in; others should, too. The supply of home-made weapons is more dependable and cheaper than Western-made ones. It can also be more innovative. Ukraine has around 250 drone companies, some of them world leaders—including makers of the long-range machines that may have been behind a recent hit on a huge arms dump in Russia’s Tver province.

The second way to make Ukraine’s defence credible is for Mr Biden to say Ukraine must be invited to join NATO now, even if it is divided and, possibly, without a formal armistice. Mr Biden is known to be cautious about this. Such a declaration from him, endorsed by leaders in Britain, France and Germany, would go far beyond today’s open-ended words about an “irrevocable path” to membership …

Actually Mr Biden is known to be doolally, a matter of small significance in the wider scheme of things but testimony to the truth that elected presidents are marginal bordering on irrelevant to the running of the US empire. But as may be gathered from my throwaway tone, I’m done with this wretched piece. If inclined, you can read the rest of it here.

Let me close by making the growingly obvious point that if we of the human race manage in the face of daunting odds to avoid a very nuclear world war three, it’ll be no thanks to shit-stirringly pretentious rags like The Economist.

Meanwhile, as I said prematurely when closing yesterday’s post (we steel city scribblers work so hard we lose track of what day of the week it is) have a good weekend!

* * *

- It’s easily forgotten, because our corporate media trade in amnesia, that Mr Zelensky was elected on a ticket of improving relations with Russia, and ending the Ukraine’s then five year old civil war by easing tensions with Russian speaking oblasts in the east. Far right Banderite nationalists forced him, on pain of his life, into a u-turn.

- The New Hitler moniker is epithet of choice for any leader in the way of imperial designs. Bashar al-Assad, Muammar Gadaffi, Slobodan Milošević, Hugo Chavez are a few of those to have been so labelled. Often paired with denunciations of the unconvinced as Munich ’38 style appeasers, if not mouthpieces for murder, it taps deeper narratives of Western superiority.

- In a February 2024 post, with the Avdiivka salient still contested, I used a WW1 analogy to distinguish wars of attrition from those of territorial conquest:

One of the most hellish examples of a salient, a bulge at the front exposed on three sides to enemy fire, was Ypres in WW1. Its third and final battle, Passchendaele, saw the war’s highest death count, at over half a million. Though often depicted as futile, that’s an assessment informed by ground taken and lost. As such it foreshadows one of many miscalculations NATO made in its proxy war on Russia. German losses at Passchendaele were lower than Britain’s and France’s, but less easily replaced – no colonials to recruit – and a major influence on the war’s final outcome. Like Ukraine, WW1 was a war not of territorial gain but attrition. The horrors of both notwithstanding, the macabre arithmetic was – and is – decisive.

- The contrast between RF patience, and politically driven decisions in Kiev which sacrifice AFU lives for propaganda purposes – never more blatantly than in the Kursk madness – could not be starker.

- What Tariq Ali dubbed the “extreme centre” has a long history of parading as a bastion against the fascism its venality and ideological bankruptcy licence. This attempt by The Economist to paint opponents of the war, and the price Europeans are paying, as dupes of the far right is all the more risible given its tissue of lies on an “unprovoked” attack on a plucky nation minding its own business. It’s of a piece, however, with a wider pattern. I sense a dedicated post coming on.

- The east’s right to self determination, following Kiev’s secession from Russia, is what the Minsk Accords were all about. At least, for its peoples and for Moscow. Angela Merkel’s boast, backed by François Hollande, of having tricked Putin formed a personal turning point for an RF President slated by his Kremlin critics as an appeaser of the West.

- Western media trumpeted that Mr Putin had rigged his victory. How did they evidence that claim? By force of repetition, always the MO of choice. As for saying he faced scant opposition – this from a USA routinely offering voters a choice between two millionaires backed by billionaires! – we saw Russian percentage turnout in the high seventies. If they didn’t like the menu, why didn’t the diners simply boycott the restaurant?

Unhinged warmongering from this fella at the Economist with the fancy title of Editor in Chief.

Appreciation for your efforts. I have neither the stamina nor indepth knowledge that you and other commenters have, although I know a lot more than most I talk to.

Hope you have a nice weekend x

Thanks Margaret – you too. But don’t undersell yourself. You’re a feisty warrior for truth!

As Lucas Leiroz over at the Strategic Culture foundation notes…..

https://strategic-culture.su/news/2024/09/28/famine-in-europe-the-real-goal-of-anti-russian-policies/

….there are longer term effects for Europe:

“Ukrainian food products have simply invaded the European market and are driving thousands of farmers out of business. Despite the protests and political pressure, no EU decision-maker seems interested in changing this tragic scenario. However, the crisis seems to have even deeper dimensions and could be a real time bomb for the entire European society….

….Selling grain, meat, dairy products and everything that is produced in the countryside seems to be no longer an attractive business in Europe. Since 2022, protests for change have been taking place in all parts of the European continent. From Poland to France, no European farmer is happy to see his products being replaced on the market by massive quantities of cheap Ukrainian agricultural items.

This is due to the irrational decision of European decision-makers to ban all import tariffs on Ukrainian food products. The measure is allegedly intended to boost the Ukrainian economy during the crisis caused by the conflict with Russia – which ironically is sponsored by the West itself. In the current European market, it is cheaper to import Ukrainian food than to resell the native products, which is obviously causing thousands of farmers to abandon their businesses.

As well known, most of Europe does not have a very strong agricultural sector, with local farmers relying on government aid to stay active in the market. Without this aid and with the invasion of Ukrainian products, it is simply no longer profitable to be part of European agribusiness, which is why thousands of people are likely to stop working in the rural areas and join the growing class of the European “precariat”.

At first, some analysts may see this scenario as a mere market shift, replacing European production with Ukrainian production. However, this analysis is limited. Despite having some of the most fertile soils in the world, Ukraine is currently a target of Western financial predators, who demand the handover of arable land as a means of payment for NATO’s billion-dollar aid packages. Organizations such as Blackrock and other funds will soon own almost all that is left of Ukraine’s “black soil.” And then Ukrainian agricultural production will depend on the willingness of the “financial sharks” to feed the Europeans….

…..The US-EU alliance is a real time bomb and in the long run it will lead Europe to famine. Already in the process of deindustrialization, energy crisis and [now] destroying its entire food security architecture, Europe faces one of the bleakest futures in human history. And almost all European decision-makers seem happy with this scenario.”

The “price worth paying” of hundreds of thousands of Iraqi children thirty years ago, along with Palestinian and Lebanese children today, will at some point in the not too distant future switch to be visited on the European continent as the parasitic corporate predators from across the Atlantic and their comprador’s in Europe take their pound of flesh by force. Despite not being in the EU the UK’s geographical location is equally precarious.

At the present rate – unless there are a lot more Rosie Duffield’s on the benches of the nominal Starmer Government – the only “Change” Herr Starmer and his Junta are likely to achieve is changing live voters into dead voters.