In a Sputnik article last month, replicated in the excellent Off-Guardian, Pepe Escobar gives a useful appraisal of the conflicting interests of China and the USA in the South China Sea. It’s a well informed piece and I recommend it, though not unconditionally. Escobar begins:

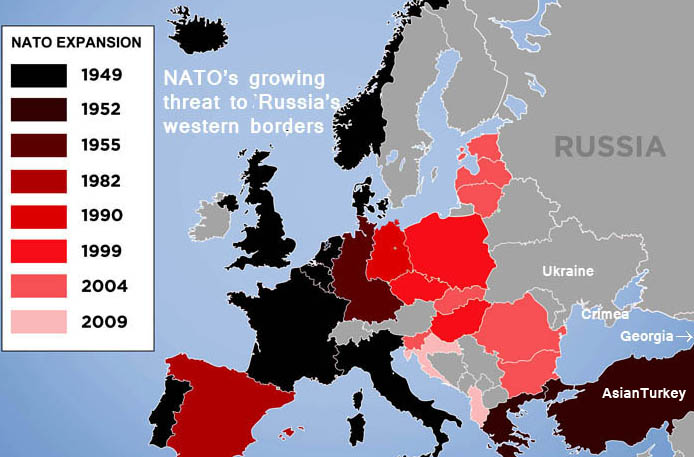

The South China Sea is and will continue to be the ultimate geopolitical flashpoint of the young 21st century – way ahead of the Middle East or Russia’s western borderlands.

Given that I agree with pretty much everything that follows this opener, am I nitpicking in my objection? You tell me.

I travel frequently to Vietnam and agree that territorial rights in the South China Sea, the narrow context of Escobar’s piece – the broader context being Sino-American rivalry – are a sensitive issue for the reasons he sets out. These are as follows. One, western colonialism is responsible for a “currently incendiary battle” in the South China Sea. Two, the late 19th century creation of Asia’s nation states by colonial fiat overlaps with China’s ‘century of humiliation’. That makes current quarrels – be they China’s damming of the upper Mekong to the fury of Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam or its creation of artificial ‘islands’ in waters claimed by Hanoi – matters as dear to the heart of the man on the Guangzhou omnibus as to China’s ruling elite. Three, while regional land borders have not been seriously disputed since Pol Pot’s day, territorial waters less well defined certainly are disputed. Four, that colonial legacy of maritime ambiguity, cause among other things of sharply deteriorating Sino-Viet relations, acquires global significance when we factor in China’s meteoric rise and the degree to which US marine bases, outnumbering those of all rival powers combined, are mission critical to the American Empire. Likewise the corollary imperative of unchallenged US access to them through control of the seas.

(One of the surprises here being a new synergy of US and Vietnamese short term interests.)

Now while I agree that America and China are headed for serious confrontation in the region, and much as I respect Escobar’s work, the South China Sea is not “way ahead of the Middle East or Russia’s western borderlands” as a potential flashpoint for WW3. All three qualify as joint ‘favourites’ in that respect. Even more important, the challenge to US Exceptionalism comes from China and Russia both and cannot easily be separated, for purposes of severity ranking, when Washington’s decisions push those two powers ever closer.

[ezcol_1third]For example in 2013 Russia made a bridging loan to Ukraine. At $3bn it was a small but significant sum, on very favourable terms when Ukraine’s credit status would have incurred punitive rates on world markets. Payment in full was due in December, after the Maidan Square coup replaced Yanukovych with a semi fascist regime.[/ezcol_1third] [ezcol_2third_end] [/ezcol_2third_end]

[/ezcol_2third_end]

Enter the International Monetary Fund. Since the US outvotes all comers, and can increase its share by arm-twisting states beholden to it, IMF rules are Washington rules. For decades these have debarred any country welshing on a sovereign debt from receiving loans by the IMF or by member states. That held for Greece last summer. But with that problem put to bed, the rules were altered. Now, Ukraine may borrow from the IMF without repaying Russia – nay, stiffing her is a de facto loan condition! Why? Because China and Russia are coming together – the one with its vast surplus, the other its vast energy reserves – to challenge a dollar hegemony going back to Bretton Woods and expanded after the fall of the USSR. Burning Russia on a relatively small sum was a shot across the bows. With the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank an emerging alternative to the IMF, developing and even western nations seeking finance might turn to the former to avoid swingeing austerity and public service cuts demanded by the latter.

(In Greece last year a European Central Bank on the whole more hawkish even than the IMF was nevertheless happy to see Athens raise taxes for the elite, if that’s what it took to repay Berlin and Brussels; German taxpayers having kindly taken on Greece’s debt in a now familiar win-win for rentier capital. The IMF was having none of it. Where creditors take a pragmatic approach to debt recovery, it’s in the DNA of free market ideologues to favour public spending cuts for their low hanging privatisation fruits.)

In a crisply forensic piece at close of 2015, with the deadline for Ukraine’s repayment ignored, Michael Hudson spells out the message from Washington:

Imagine the following scenario five years from now. China will have spent half a decade building high-speed railroads, ports, power systems and other construction for Asian and African countries, enabling them to grow and export more. These exports will be coming online to repay the infrastructure loans. Also, suppose that Russia has been supplying the oil and gas energy for these projects on credit.

To avert this prospect, suppose an American diplomat makes the following proposal to the leaders of countries in debt to China, Russia and the AIIB: “Now that you’ve got your increased production in place, why repay? We’ll make you rich if you stiff our adversaries and turn back to the West. We and our European allies will support your assigning your nations’ public infrastructure to yourselves and your supporters at insider prices, and then give these assets market value by selling shares in New York and London. Then, you can keep the money and spend it in the West.”

How can China or Russia collect in such a situation? They can sue. But what court in the West will accept their jurisdiction?

We might add that the likelihood of such a scenario rises exponentially where, twixt loan and payday, the borrowing government is ousted – in the name of democracy and to mood music of corporate media demonising – by one beholden to Washington. Yanukovych’s and Eastern Ukraine’s favouring of Moscow over the west are a big factor in the default. As are Victoria Nuland and the impeccably timed Maidan coup that empowered fascists, yes, but America-friendly ones.

We might also add that the approach of this hypothetical American diplomat is premised not only on the relative military might of these rival powers but – Hillary supporters take note – on their perceived willingness to use it. To Clausewitz’s axiom of war being politics by other means we can attach the Marxist one that politics is economics by other means. We can go further still and see the AIIB’s fiscal threat to The Empire of Chaos as a trade threat when, as Wall Street well knows, commerce and profits follow ‘overseas aid’ as night follows day.

Pulling all this together, we see in Ukraine’s default a symptom of aggrievements that may one day, and that day may come soon, bring us to close encounters of the thermonuclear kind. It is therefore right and proper for Pepe Escobar to remind us of the seriousness of the situation in Asia, of the plethora of America’s marine bases and of the fact it will do all in its considerable power to maintain control of the sea lanes. But whether it is helpful to prioritise any one of the three identified flashpoints over the other two; that is more debatable when the whole sitch is (a) deeply interwoven and (b) seriously scary.