Be of good comfort, Master Ridley, and play the man! We shall this day light such a candle, by God’s grace, in England, as I trust shall never be put out.

Bishop Latimer: October 16, 1555.

On this day five hundred years ago an exasperated preacher and professor in moral theology is said to have nailed his ‘grievances’, ninety-five theses written in the spring and summer of 1517, to a chapel door at Wittenberg Cathedral. First in his sights was the trade in indulgences, papal promises signed by this bishop or that to expedite the progress of the purchaser’s soul through purgatory. One practitioner was Dominican friar Johann Tetzel, seller of indulgences who rose to become Grand Inquisitor of Heresy to Poland, aided by a ditty Madison Avenue itself could not have improved on:

… when gold into the coffer rings, the soul from purgatory springs …

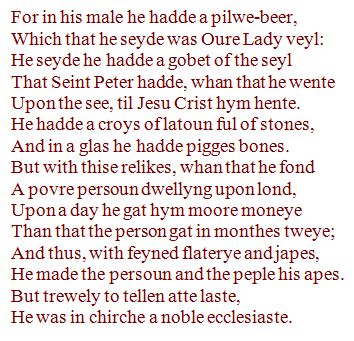

Disgusted of Wittenberg – a Martin Luther soon outflanked by fiercer critics of Rome – was by no means the first to look askance on such practices. Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, written in the fourteenth century but only published in the last quarter of the fifteenth, gives us the Pardoner. This fellow – “thin and droopy” … hair “yellow as wax hanging lankly” … eyes like a rabbit’s and voice like a goat’s (icons then as now of lechery) – tops up his commissions on indulgences, for which he’d have to account, by way of a more lucrative racket. Why disturb the bishop’s men with details of “pigges bones” traded as those of an apostle’s finger?

Chaucer was a contemporary of John Wycliffe, leader of the Lollards and scathing not only of indulgences and relics but a bloated clerisy at large. It’s true that just as Luther would distance himself from Men Who Went Too Far, men like his erstwhile comrade Thomas Muentzer, so had Wycliffe baulked at a Peasants’ Revolt backed by the more firebrand of his Lollards. But his attacks, initially ad hoc, would evolve, as such criticisms will, into more doctrinal form; viz, that papal authority has no scriptural basis.

Wycliffe predates the Reformation by more than a century. He never saw the bible translated into English by Luther’s contemporary, William Tyndale, but would have been unsurprised by the consequences. Tyndale, like lawyer and fellow traveller James Bainham, did not have to await Mary Tudor’s short but vindictive reign for martyrdom at the stake. His work drew the wrath not only of men like Thomas More but also a Henry VIII dubbed Defender of the Faith by Pope Leo X until, less the fervent Protestant than disobedient Catholic, his lust for Anne Boleyn and need of a male heir saw him break reluctantly with Rome. In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God may strike our secular age as superstition – and the materialist as philosophic idealism to be countered by in the beginning was the Deed – but its revolutionary significance at the time was clear to Church and Reformers both. A bible devoid of reference to pope, bishop or purgatory posed in any vernacular translation, let alone one whose publishers insisted that God’s Word could be heard without priestly mediation, an intolerable threat to a divinely ordained status quo – and, except where it suited one contending faction or another, its ruling class.

We might note in passing that according to Melvyn Bragg, the King James version, an early jewel in the crown of that flourishing of arts and sciences under the Stuarts, has been shown by recent textual analyses to be almost seventy-five percent Tyndale – rising to ninety percent for its New Testament:

“under the sun”, “signs of the times”, “let there be light”, “my brother’s keeper”, “lick the dust”, “fall flat on his face”… on and on they march through our days, phrases, some from his childhood in the Cotswold countryside, some from Anglo-Saxon and Hebrew, all alchemised into our everyday language …

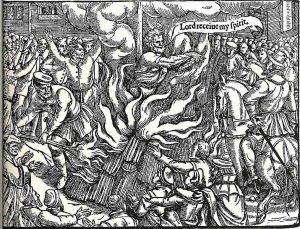

Wycliffe escaped the full wrath of the Church in his own lifetime. It was stroke, not stake, that took him in 1384. Not until 1415 was he declared a heretic, his body exhumed from consecrated ground, bones ceremoniously burnt and ashes flung on the River Swift upstream of Lutterworth. Meanwhile his ideas had been taken up by a brilliant Czech academic whose final words were croaked out as, a guarantee of safe passage declared non-binding if made to a heretic, torches of burning pitch lit the firewood and straw piled around him at the gates of Konstanz Cathedral. Jan Hus, one of the ablest scholars of his day and, like his mentor, ahead of the Reformation by a century, was paying a price that Luther – unlike many of those he inspired: Latimer, Cranmer, Anne Askew and countless others incinerated by Bloody Mary and Bishop Bonner in England, and by Counter-Reformation across Europe and beyond – would not be called on to pay.

Hus’s execution sparked the Hussite Wars, 1419-34. Initially between Hussites and forces loyal to the papacy, these soon turned in on themselves as, foreshadowing many a Protestant split, Hussite factions confronted each other. Of particular note here are the Utraquists whose tightly organised footsoldiers and archers saw off five papal crusades, only to side with Rome against the more radical Taborite Hussites. And win. And be rewarded by being allowed to practise an unorthodox but nonthreatening version of the Faith.

(For light on this we might turn to Freud, who gave us the term ‘narcissism of small differences’. But while the ego’s drive to locate itself in difference is seldom far from the crime scene in such schisms, it is in this case overshadowed by the realpolitik of a dangerous age.)

*

I’m jumping back and forth in time because, as with many a tale, the narrative laid out in strictly chronological sequence can miss things that matter. One being that few if any of these men and women wanted to die. Hus did not defend himself by grandstanding about being answerable to a Higher Authority than that of his accusers. Rather, though he had cause enough to protest the circumstances of his arrest, he rested his case on having been misunderstood. For his part and a hundred and forty years on, Cranmer did recant, and not just the once. That by custom should have spared him so cruel a death but the divine gleam in Mary’s eye shone brighter than usual in his case. As Archbishop of Canterbury, Cranmer had not only driven through the divorce of her mother – even ‘threatening’ Henry with excommunication should he have further sexual relations (as if!) with a brother’s widow – but had with his own hands placed Catherine’s crown on Anne Boleyn’s head. Had Anne borne a robust son, and so saved her own life, Mary would at this point be at best sewing smocks for the poor in some farflung convent, not following Jane Seymour’s sickly son Edward, and nine day Jane Grey, to the throne. And not using Protestants to light her bonfires. Doubly betrayed – his life by Mary’s refusal to play the game; his soul by his own survival instincts – Cranmer went to the stake in 1556, six months after Latimer and Ridley, recanting his recantations:

And now I come to the great thing that troubleth my conscience … the setting abroad of writings contrary to the truth. Which here now I renounce and refuse, as things written with my hand contrary to the truth which I thought in my heart, and writ for fear of death, and to save my life, if it might be: and that is, all such bills, which I have written or signed with mine own hand, since my degradation; wherein I have written many things untrue. And forasmuch as my hand offended in writing contrary to my heart, therefore my hand shall first be punished. For if I may come to the fire, it shall be first burned. And as for the Pope, I refuse him, as Christ’s enemy and antichrist, with all his false doctrine.

Personal considerations aside, Cranmer’s downfall and subsequent demeanour left both sides with an uphill struggle claiming moral victory. Besides taking the edge off her schadenfreude, that last act of defiance robbed Mary and Rome of the propaganda boost they’d sought. Then again, Cranmer’s vacillations had left the protestant cause little enough to crow about – though John Foxe gave it his best shot, his pictorial record of the execution in Foxe’s Martyrs leaving for posterity a vision of that ‘offending’ right hand offered first to the flames by its owner.

This is an aside but a major one given the recurring Reformation theme of dynastic insecurity. That Anne Boleyn’s daughter Elizabeth survived Mary’s thirst for vengeance is down to legal obstacles not easily skirted. While the Succession Act of 1544 had not annulled the ‘bastard’ status of Henry’s daughters, it had restored both to the royal line. Since ancillary legislation made defiance of the Act treason, Jane Grey had, regardless of Protestant Edward’s will, played for the highest stakes.

This is an aside but a major one given the recurring Reformation theme of dynastic insecurity. That Anne Boleyn’s daughter Elizabeth survived Mary’s thirst for vengeance is down to legal obstacles not easily skirted. While the Succession Act of 1544 had not annulled the ‘bastard’ status of Henry’s daughters, it had restored both to the royal line. Since ancillary legislation made defiance of the Act treason, Jane Grey had, regardless of Protestant Edward’s will, played for the highest stakes.

(In such heady times it’s not easy to sift personal ambition from conviction that God was calling on Jane to advance – or in Mary’s case roll back – the Reformation, nor from dread of Letting Him Down. The separation is harder still given powerful and eloquent voices in the wings, their owners likewise exposed in a zero sum game; flattering and coaxing, bullying and advocating.)

Of course, legal niceties would have counted for nothing had efforts to capture Mary in those first critical days after Edward’s death succeeded. As noted in the context of Catalonia, laws are written in ink; underwritten in blood. But Mary was not captured and did Rally The People. The Privy Counsellors – sensing a winner, not bent on martyrdom and in any case wanting no rerun of civil wars whose tail end a few were old enough to remember – switched allegiance to seal Protestant Jane’s fate. Protestant Elizabeth was a different proposition though. Mary could not deny her half sister’s place in the queue without invalidating her own. What she could and did do was place the young princess on the shortest of leashes – including spells of house arrest – and pray for longevity, the latter in vain.

Also notable for its theme of devotion giving courage to defiance is that the seventeen year old Jane might have saved herself. Scholars tell us her death was inevitable after her father joined Thomas Wyatt’s rebellion over Mary’s planned betrothal to Philip of Spain. (The 1544 Act had forbidden the royal heirs from marrying without Privy Counsel approval.) But days before the execution, Mary sent her own chaplain to convert Jane. The nine day queen who’d condemned Mass as “wicked” and urged all Protestants to “return, return again to Christ’s war”, was having none of it. She lost a Protestant head but might she have kept, albeit in reduced circumstances, a Catholic one? The question brings us, via another leap back in time, to Mr Bainham.

It’s hardly proof, but the portrayal of James Bainham in the BBC screening of Hilary Mantel’s quite brilliant Wolf Hall is compelling. We see an ordinary man in an extraordinary situation, gripped by an all too understandable terror at his fate. But it’s a fate he could avert by uttering a few words: “just words”, as the kindly Thomas Cromwell of the Beeb’s at times anachronistic imagining urges him. He can’t utter them though. Real as the flames of Smithfield are to him, realer still are those of eternal damnation. And that’s the second of the truths to be brought out here. For all their doubts, and for that matter their hubris, these men and women died, or risked, terrible deaths for what to them was Truth non negotiable. We’d have to be lacking as much in imagination as human feeling not to be impressed.

This segues into a third truth, but let’s first set the record straight. Protestantism had and has no monopoly on martyrs. I say this not in a spirit of fairness but because such heroism, such depth of faith, is not easily separated from realpolitik. The conservatives got Hus in the end, but why had he been allowed for so long to preach the gospel according to Wycliffe? Because he had the patronage of King Wenceslaus IV, a man with an axe to grind. The papal schism early in the fifteenth century, between supporters of Gregory XII in Rome and those of Benedict XIII in Avignone, saw Wenceslaus championing Benedict because he feared Gregory would stymie his shot at Holy Roman Emperor. When he ordered Bohemia’s clergy, university included, to stay neutral on the schism the influential Hus, unlike an Archbishop Zajíc who declared for Gregory, ordered his dons to do just that. It’s a fascinating story but my point is simply the interplay of power politics and devotion. Whatever games Wenceslaus was playing, in assessing Hus and all the others who took their faith to the wire, we must walk a fine line between credulity and cynicism. A stance of generous scepticism would seem to be in order.

Devotion and power are equally entwined in the case of English Catholicism’s most celebrated martyr. Such is television’s ability to shape our perceptions, it’s hard to set aside in the interests of more grounded assessment Thomas More’s depiction in Wolf Hall by an Anton Lesser who excels at unsympathetic and/or morally complex characters. We can fairly conjecture though that More’s positions on a range of interwoven matters, from Tyndale and Bainham (each of whom Cromwell had indeed tried to save) to Henry’s annulment and Anne’s coronation, stem more from the views of the one time humanist now fearful – it’s a common enough trajectory – of earthly chaos than unshakeable faith in the Old Religion. Can we even separate the two? Can we ever tell brilliant lawyer and wordsmith from canny theologian and intransigent patrician?

But the clearest Tudor signs of faith inseparable from realpolitik and statecraft are afforded not by Henry’s reign or Mary’s but Elizabeth’s. Hers is marked by a pragmatism her father in fits and starts aspired to but was temperamentally incapable of, while Mary didn’t even try. And though Elizabeth ruled at a time when Protestant zealotry, real or adoptive, posed in the early years as big a threat as Catholicism, the latter provided the greater body count. Just as the paranoias and ambition, four centuries on, of a Joe McCarthy would be underpinned and/or inflamed by a new superpower projecting its demons on The Other, so did real fears of an Enemy Within plotting with Spain to roll back the Reformation and place Philip or a proxy on her throne add urgency to Elizabeth’s persecution of Catholics. So too, for a dynasty whose founder grabbed the crown at Bosworth and whose legitimacy remained contentious, did fears of Plantagenet resurgence decked out in holy garb. Which brings us back to those Catholic martyrs and their belief – every bit as sincere as that of their mirror opposites; every bit as prone to appropriation by worldlier designs – in their own salvation and the damnation of fellow Christians they could never bring themselves to recognise as such.

*

In sum: one, these were not fanatics bent on glorious deaths. Some had protection more pliant or less powerful than they’d supposed; others were simply naive. Two, they showed a courage we can only attribute to faith which may have wavered but did not desert them. Three, they died in times which – ironically on one side, given that Lutheran emphasis on a personal relationship between Man and Maker – had not the luxury of dividing private from public realms. Or to put it in terms already used, faith and politics were not easily separated.

But what did it all stack up to, this Reformation? Well might we ask, and well recall Zhou Enlai’s reply to the question, allegedly put to him the best part of two centuries after the fact, what did the French Revolution achieve?

I like to think Mao’s old comrade really did answer – tongue half but only half in cheek – that it was “too early to tell”. All knowledge is provisional, as good scientists know. And as good historians know, all judgment on momentous events is even more so. The Reformation surely falls into that category, and historians have not the natural scientist’s privilege of establishing causality by means of controlled and repeatable experiment. Beyond Reasonable Doubt is the best we can aspire to, and in this case not even that.

I start as Luther pace Wycliffe did, with injustice rationalised by cant. The idea of a soul sped to heaven by cash payment to a priesthood now unites believer and non believer alike in aghast incredulity. Twas ever thus. The crimes and absurdities of times gone by are crystal clear to our so clever, end-of-history gaze – what wolves and sheep they were; what rogues and fools! – but should humanity survive, a time will come when belief in the superiority of market anarchy over wealth creation planned by and for humankind will evoke a similar response. Ditto the fact of fewer than a dozen men owning half the world, while scores of millions die in destitution and arms profits in and of themselves drive industrialised carnage. Cry Godwin’s Law if you will, but why would these things not seem as monstrous to our grandchildren’s grandchildren’s age as the nazi holocaust to ours?

There is an answer to that but it’s not good news. Not only is every generation desensitised to greater or lesser degree to the horrors of its day. And not only are we in the West sheltered from those endured by peoples at best not psychologically real to us, and at worst out of sight and out of mind. The horrors I speak of flow from laws of motion few understand (least of all economists, their salaries dependent on their not understanding) and which leave us with clear beneficiaries, yes, but not identifiable agents in the sense of individuals who by making other choices could reverse those laws of motion. On the contrary, by making different choices those agents would see their ‘power’ evaporate in an instant. I call them a ruling class, and with good reason, but ultimately that’s no more than a useful fiction when they too are enslaved. In our day the Henry Tudors and Heinrich Himmlers, ogres whose humanity we must deny to reaffirm our own, are thin on the ground but their elusiveness is that of a world amok: an Isaac Asimov dystopia without the robots.

Relieving an illiterate peasantry of its hard-earned was tip of an iceberg for Luther. As Hus and Wycliffe had, he came to question Rome’s fusion of spiritual and temporal authority when a priesthood, its upper echelons living as princes while debauchery and venality operated at all levels, interpreted for the masses a text whose vernacular translation was a capital offence. For all the scheming of a Henry Tudor, and for all the hesitance and worse of a Martin Luther, the Reformation was in no small part a fight against earthly injustice.

There’s more. Historians differ on how much an equally momentous process, the eighteenth century Enlightenment, owes to the Reformation. Some find more direct antecedence in the Renaissance; some point to a Catholicism amply represented in both scientific enquiry and the thoroughly modernist project, its clearest manifestation the French Revolution, of changing the course of history on the basis of a Big Idea. Responding to the first argument, Renaissance and Reformation are not mutually exclusive candidates. The second implicitly views Protestantism and Catholicism as inhabiting parallel universes. A moment’s thought reveals the absurdity of assuming a Vatican deaf and blind – even if Rome did wait until 1822 to cease its attacks on heliocentrism – to ideas it could no longer suppress. Dafter still is the notion of individual Catholics, the intelligentia in particular, miraculously unacquainted with Lutheran, Calvinist and secularist currents.

Even at the level of theology, secularists see the Protestant view of the transubstantiation as a step in the right direction from insisting the Eucharist bread and wine literally become Christ’s flesh and blood. But here too we must be careful. America’s baptist belt holds no shortage of folk convinced the earth is six thousand years old, dinosaur bones God’s test for the faithful and black people descendants of Ham the betrayer of Noah. For his part Ian Paisley vilified ‘papist superstition’, but the Free Presbyterian Church of Ulster he co-founded is no stranger to blind fundamentalism. Not that the ‘Troubles’ should ever be understood as religious in nature or origin. My point is that even in spiritual terms, with its social justice aspects artificially stripped out, the Reformation sits easier with the Age of Reason than does papal infallibility. Which is emphatically not the same as declaring Protestants more rational than Catholics! Or even that rationalism is the be all and end all of human inquiry. In a universe jam-packed with unknowns, and perhaps unknowables too, the limits to rationalism and for that matter empirical methods are epistemologically understood. Likewise the acts of faith they rest on. But in gauging the Reformation’s contribution to events in the second half of the eighteenth century, its elevation of rational argument over “Saint Peter’s last will and testament” can hardly be ignored. Not even when said rational argument builds on beliefs many of us find fantastical.

My final argument for the Reformation as a progressive force – its theological drivers, bloody powerplays and dashed hopes notwithstanding – is that whatever men like Luther and Tyndale thought they were up to, in vernacularising the bible and declaring the priest’s role less than pivotal they did more than change the way millions of christians see their relationship with God. In 1994 David Olson’s The World on Paper drew on evidence, much of it counterintuitive and not always kind to cherished assumptions, from many disciplines for answers as to how literacy impacts on thought, in both its individuated and cultural forms. Within a much broader historic sweep, Olson makes the telling but underappreciated point that in opening up the possibility of God’s will as decodable by all inquiring souls armed with the tools of literacy, the Reformation introduced another: that divine intent could similarly be ‘read’ in nature. Might creation too be an open book to those willing and able to master the code? One way of viewing the explosion of inquiry marking the late seventeenth century, the age of Boyle, Hooke, Newton and Wren – christians all – is that the giants whose shoulders they stood on include in one century Jan Hus, in another Askew, Bainham, Cranmer, Latimer and so many others: men and women who went to terrible deaths for convictions which in Newton’s own lifetime, and in strikingly similar garb, had returned to overthrow a king. So what if England’s revolution did falter, and did enthrone that king’s son? Monarchy was altered for good: the divine right of kings, like papal infallibility, kicked into the dustbin of history from which it has yet to emerge. Luther would turn in his grave but who, on the basis of evidence and reason – evidence and reason – would swear he had no hand in all that followed his hissy fit of October 31, 1517?

*

Again: historians have not the natural scientists’ luxury of controlled experiments. They can’t remove the Reformation and rerun history to see whether we still get an Isaac Newton, still get a Charles Darwin, a Voltaire, a French Revolution and for good measure a Russian one. It can be argued of course that science is defined less by method than by predictive power; that what distinguishes physics from voodoo is not white coats and particular methodologies but the fact one can propel us, on the basis of ‘if x + y then z‘, thousands of miles through the air at thrice the speed of sound while the other has yet to deliver on flying carpets or astral travel. But we can’t separate historians’ inability to run controlled experiments from their inability to make causal connections that are empirically unassailable. It’s not that history deals with the past. So too does an evolutionary theory that has furnished elegant examples of predictive power; of life forms found because we looked for them, convinced by models of naturally selected random genetic mutation that they must exist. The problem for history lies elsewhere, and confronts all the human sciences. That’s our species complexity, individually and societally, and the myriads of turning points it engenders at every moment. ‘If x + y then z’ doesn’t entirely work here. No law of the cosmos ruled out a Catherine of Aragon, never mind an Anne Boleyn, giving Henry a strapping son or two.

But in the wider scheme of things Henry’s desires and agendas, like Wenceslaus’s, fall into the category of small events while the Reformation was a Momentous Event. Small events may be catalysts for but not causes of Momentous ones. We can say with a confidence close to Beyond Reasonable Doubt that the Reformation had to happen for reasons way beyond securing the Tudor line; such as that the rise of mercantile capitalism created tensions insoluble within the absolutist worldview Martin Luther – objectively and, again, regardless of what he may or may not have believed he was up to – railed against on that church door. Tensions we see replaying in later times between old money and new; brittle certainty and dangerous discovery. Tensions whose drivers have a habit of tossing aside the agents – the Tyndales and Tudors, Dantons and Bourbons, Kerenskys and Romanovs – who’d thought to control their pace and direction.

By the same token that upsurge in scientific enquiry of the late seventeenth century can hardly be chalked up to Charles II, a quite unremarkable man. But then, history has ways of making use of whatever materials are to hand, even mediocrity: witness, a century on from the Stuarts and on the far side of the Channel, the empty headed vanities of an aristocracy which, having sown the wind, now stood to reap the whirlwind. Those vanities did not cause France’s transition to capitalism – that was going to happen come what may – but did ensure she got there by the most violent route.

All the more profoundly, then, can history write its futures with materials as wild and abundant in possibility as those the Reformation hurled into being. To what end? Too early to tell.

***

Fascinating how one man’s thoughts, ideals and challenges are capable of multiplying and by doing so, changing the course of history. A fine piece of writing with detailed and thought provoking observations.

Thank you, J Thorneycroft.

What an effective weaving together of the influence this cast of characters has had on our modern day lives. Complex and rich analysis, and enjoyed the tremendous roll-call of names (at least 43!) swirling around the themes. Enjoyment marred by the very fleeting comment on Elizabeth – I can only think of her through a gendered lens: perhaps another post? – and the fact I don’t recall James Bainham’s role and you never quite said. An assumption too far on your part or ignorance on mine? I did, though, resist just looking up Wikipedia to read about him.

Bainham is the guy, clearly terrified, who as Mass is being conducted in Latin reads aloud from Tyndale’s translated bible. We see him later in the Tower, still terrified but rejecting Cromwell’s offer to whisk him out. That scene ends with Bainham trying to prepare himself by holding his hand above a candle flame. His body’s own reflexes cause him to withdraw it instantaneously. It’s as neat a way of driving home a dramatic point as I’ve ever seen.

43, huh? You counting Joseph McCarthy? Christopher Wren? Georges Danton?