I won’t lie. The Broads rarely rise above pleasant to pretty for walkers or cyclists. To see them at their breathtaking best you must get on the water. In fact you must get on the water in a craft able to glide through marshes at dawn or dusk, or up a barely navigable North Walshham and Dilham Canal, as Jackie and I did yesterday; ducking under arcing alders, else grasping fistfuls of reed to pull our way through dark swirling channels – canals do have currents, this one north to south and racier than most – scarcely two feet wide. Twice we edged by swans with cygnets – not, mercifully, in those narrow cuts offering nowhere to get out – as fathers thick in the neck gave warning hiss while we gave what room we could, and made placatory vocalisations. Four times we saw the unforgettable flash – you haven’t seen it, you haven’t lived – of chestnut on electric blue of a kingfisher speeding across the water, while everywhere we were locked in the embrace, claustrophobic in circumstances less idyllic, of banks bedecked in forget-me-nots and crowding bulrush, or under a dense canopy of oak, alder and weeping willow.

Even at its most weed choked the canal, thanks to dedicated volunteers – we dropped our £4 of suggested donation into a box a mile up the bank from Wayford Bridge – offered sufficient depth. Not until the weir at Honing were we obliged to get out.

Nothing here the kayak couldn’t handle …

… nor here …

… nor yet here, in this scene from The African Queen.

For the rest of these halcyon days – we arrived Monday evening and left Saturday evening – I’ll stick in the main to pictures. Starting with the staithe at the southeast edge of Horsey Mere.

Until very recent times, the Broads were thought to be naturally formed. Only in the sixties did botanist and ecologist Joyce Lambert show them – her proof the stepped shelves discernible to divers only when cleared of a millennium of silt – to be the product of medieval peat digging, probably to meet growing energy demands from Norwich, its star rising under a succession of Plantagenet kings.

This was my second visit afloat. The first was in 1966, when dad hired a cabin cruiser the week Bobby Moore & Co took England to its last world cup victory. I mention this because, though it was a great holiday, the Norfolk Broads, more intensely managed than any other national park, are now in better shape. Several reasons for this, most importantly that the fish which attract anglers en masse feed destructively on molluscs and other invertebrates which, themselves feeding on algae, keep the waters clear. That’s how the Broads looked before tourism began in the twenties, intensifying in the sixties and seventies to the point where its effects looked set to kill the golden goose. A key task is to remove fish from designated waters to give respite for the molluscs. Only when invertebrate populations become self sustaining are fish reintroduced. The results, visible in before-and-after aerial photographs, are striking. Rivers and meres that in the sixties had the opacity of village ponds – their murky surfaces literally putting a lid on things to inhibit photosynthesis and consequent food chain – now have the clarity and biodiversity of a trout stream.

For info on this success story, and much besides, the small museum of the Norfolk Broads is well worth a visit. It’s on a staithe at Stalham, three hundred metres from our third, final and favourite camp site, and visited by us on one of the two rainy afternoons of our stay.

You might also try Graham Swift’s Waterland, re-read by me while kayaking on Windermere. I admit I found his style somewhat prolix the second time round – I suspect because I haven’t the patience for verbosity I had in the eighties, and because literary tastes have moved on to reflect the screen’s growing impact on fiction – but it still packs, in a page turning yarn, a mine of info on the ecology, drainage and socio-economic history of England’s fens.

Here’s the museum’s mock up of a working wherry – flat bottomed boat plying the Broads from Yarmouth to Norwich with loads of grain, reed, timber and peat or coal – moored at a staithe. Old Norse word, that …

… with a life size model, doubtless romanticised, of its cabin.

After WW1 the leisured classes began visiting the Broads, slumming it on converted wherries …

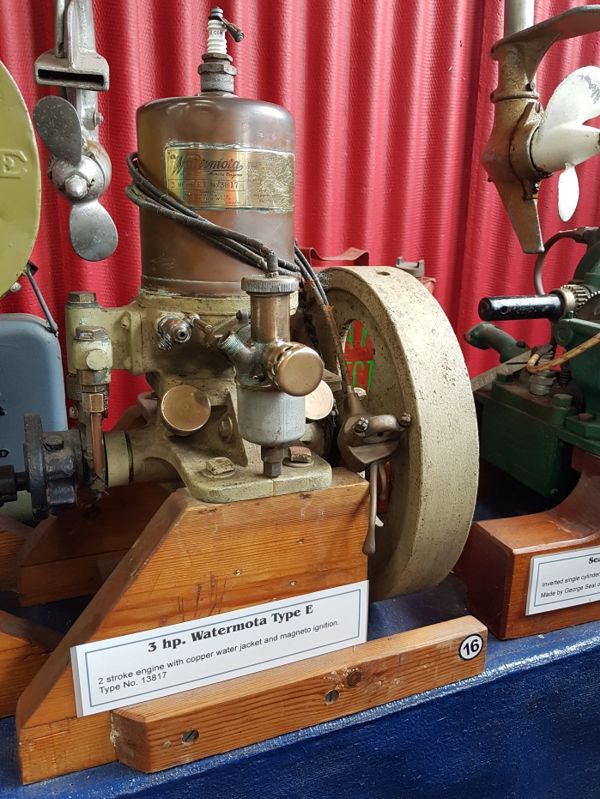

… the museum continuing the tourism theme with a fascinating run – get me on this subject and there’s no getting me off it – through the ontology of the outboard motor.

My eye – yours too I’ll be bound – is drawn instantly to esox lucius, aka pike or luce, as telling an icon as any for Broadlands fauna. Above it is a perch while to the right, seen less often than other coarse fish and in this case too large in relation to the pike, is a tench.

In no particular order and under no organising principle other than that I saw fit to photograph them, a few more. Starting with two icons: the bridge at Potter Heigham, and mill at Mundesley.

An ubiquitous sight, this, throughout our visit:

I could dedicate a post to churches visited; at least half a dozen, while many others drew our attention. Historically and architecturally interesting, lovely to behold, they merit more than these few snaps.

St Peters at Repps. Round towers are rare, and almost exclusively East Anglian.

Horsey All Saints also has a round tower and, visible here, thatched roof.

Here’s the fifteenth century rood screen at Barton Turf, hosting a flower show when we visited.

Here’s a close up on the work of those medaeval craftsmen …

… while here’s a close up on the work of men in the pay of Thomas Cromwell, Joseph to Henry VIII’s Pharaoh. More recent and rather more thorough vandalism by the Taliban, on the statues of Buddha at Bamyan, springs to mind.

But in the wider sheme of things it’s all water off a duck’s back. Or a great crested grebe’s or, at a push, young adult swan’s.

Early one evening we stopped for a pint at a pub whose gardens stretched down to Ormesby Broad. A woman, Spanish as it happens, sipped San Miguel at the next table while her cockney suitor – you could tell by the content of his oafishly complacent monologues she hadn’t known him long – droned on and self importantly on. I don’t know whether the señoritas do that nail filing thing, but her body language – playing with hair and casting frequent eye on cell phone – spoke of the less than raptly attentive. Can’t say I blamed her. I do wonder at moments like this if She finds He as tedious as I do – finds him, in the words of Paul Simon, alright in a sort of limited way for an off-night – or if I’m projecting. Maybe he’s ace in bed. Maybe I’m misreading both sets of signals, and actually she finds him riveting. I just hope she doesn’t suppose him the archetypal Englishman is all.

One afternoon we went to the seaside …

… where else would you want to eat Cromer crab, at a table for two in an alcove overlooking the pier from which, in 1962, I caught a dab and brought it back for mum to cook?

Then cast your shadow across the evening streets?

Two afternoons it rained for several hours, at times intensely. This highland diasporan, far from his roots, gave baleful warning of impending deluge as we paddled down the Ant.

Minutes later we were sheltering under a beech.

The sunsets? Outrageous.

Late Saturday afternoon, knowing we’d head homewards that evening, we arrived at the River Bure to put in for the second time that day. We’d promised ourselves one last hour afloat, from one of Norfolk’s few places of (barely) whitewater at Horning Mill, to a mile downstream at the Rising Sun in Coltishall. And back of course.

We didn’t know it till we arrived, but mill pond and surrounds are a hit not only with swimmers and canoeists but also with local youths, one gang happy to let us clear their litter after they’d toked on a brace of joints and scoffed a tube of Pringles before pissing off to pastures new. Nor that an angler would be casting pike bung and dead-bait upstream and across, only to move on in disgust at the arrival of two Mike Nelsons.

Mike who? You have to be well north of sixty to get that cultural reference.

It’s a happening kind of place, is Horning Mill. Imagine the envy tinged admiration of this lad. At his age I’d have parted with six months’ spendo to be in their flippers.

For us though, it was downstream toward Coltishall …

… and back. To beach and deflate, cook and dine, cram our all into boot and back seat, then hit the road for Sheffield by way of Norwich, Kings Lynn, Sleaford and Newark. With clear roads all the way, we were home in well under four hours. I generally reckon on five.

*

You are so right Phil – the only way to see the Broads is from the water – and preferably from a non engined craft. Great pics of a very familiar water / landscape – the bridge at Potter brings back memories of many a scrape and reminds me that we have to navigate through it again in September in a yacht during a period of spring tides when clearance will be very tight!

Good luck with that Bryan. As you said a couple of weeks ago – thanks by the way for putting me onto the Broads as kayaking venue – Potter Heigham Bridge filters out the biggest motor boats. Later, a shallowing River Thurne applies a finer filter while, to the west, a shallowing River Ant does similar.

What an incredible summer this has been! Jackie’s not big on wild camping but I kept a keen eye out for likely pitches and I’ll be back, maybe later this summer – word is it’s set to stretch into October – on my tod; by train and bus and, of course, by kayak.

Many pleasant views of landscapes,, flora and fauna, you obviously enjoyed every minute.

Every minute, Chas