In a recent post I quoted a well known figure from memory – never a good idea in public – of his 1996 interview with the BBC’s Andrew Marr. The figure in question, Noam Chomsky, made his mark initially in linguistics, where his contribution can be summarised as an insistence on the need for a transformational grammar in natural language acquisition, and a more dubious proposition – akin to invoking God in scientific explanation – that only by possession of what he calls a language acquisition device (LAD) could human beings, in almost all cases by the age of three, possibly rise to the daunting cognitive challenge of learning to speak.

But I was not quoting the man as linguist. Chomsky is now known beyond linguistic circles as a radical opponent of global capitalism, in particular for penetrating critiques of the way we are misled by a media whose political economy ensures that, regardless of the subjective honesty of journalists (and I believe, albeit with growing difficulty, that most journalists are subjectively honest) we in the West are deeply misinformed about the world and the roles of our rulers in it.

Here are the words I attribute to Chomsky, as spoken to Marr:

… I am sure you believe everything you say. What I am saying is that if you believed something different, you wouldn’t be sat in that chair interviewing me.

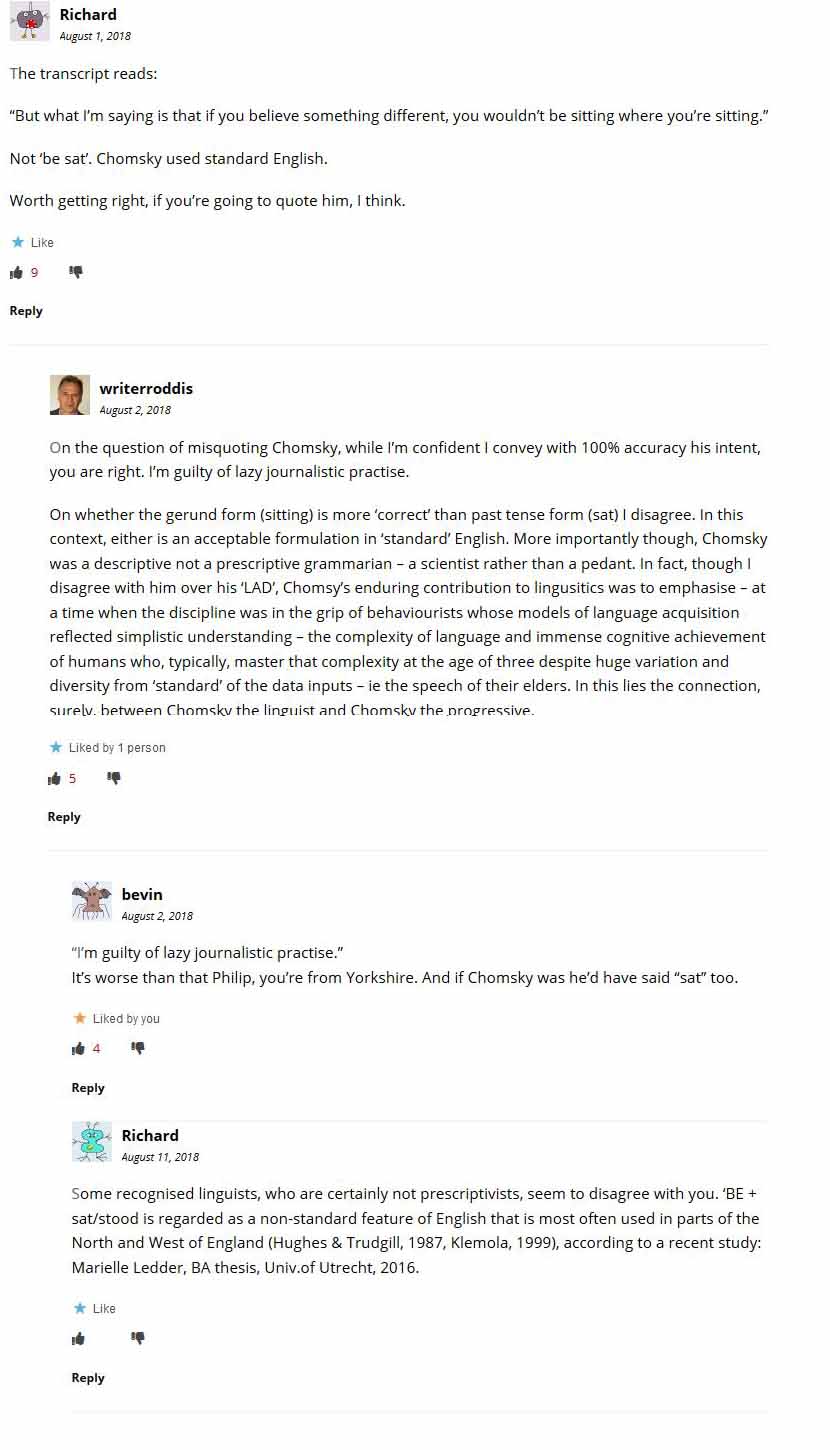

My post was reproduced in the excellent OffGuardian, where it has drawn, at time of writing, 119 below-the-line comments. Tucked in among them is this exchange:

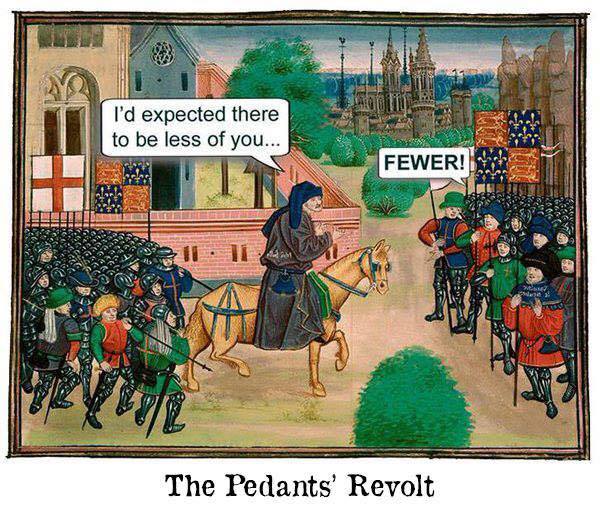

Generous soul that I am, I let Richard have the last word. But stuff like this gives me pause for thought on the nature of writing. Anyone who looks into that, whether as writer or disinterested inquirer coming at the subject without preconceptions, will surely see that a key aspect is the juggling of a formidable array of constraints. Writers constantly switch gear between high level abstraction and such low level1 detail as verb-subject agreement (easily breached in the multi-layer phrasings that writing permits by its freeing up of memory) and the avoidance of comma splicing. In my political writing, for instance, I strive to be fresh – not to bore or alienate readers with mind-bypass cliches of the ‘running dogs of capitalism’ and ‘presstitutes’ sort – and above all to be truthful. At the same time I seek to work with and for the most part within grammatic rules, but without fetishising them.

Without fetishising them. That’s critical. I see writing as rule based but creative. The rules are not set in stone, other than for those less interested in communicating than in asserting often as not class superiority. For the rest of us, committed writers in particular, and to a degree varying with communicative context and genre,2 they shift to keep up with the demands of language’s two core functions: as tool for communicating, and as tool for thinking.3 So if you tell me I must not split infinitives, nor end sentences with prepositions, I’ll ask why not. And if you want less mashed spud but fewer sausages, please tell me why, if the distinction has any merit, there’s no corresponding distinction for increments: more mash, but manier bangers …

… not that such musings excuse my laziness. That I supplied the link to the transcript Richard makes such devastating use of, in demolishing my case against the idiot d’Ancona, hardly mitigates things. In fact it worsens my crime, highlighting the fact I couldn’t be arsed to check, even when at proverbial fingertips, the exact form of words used. I told the world that Chomsky – who, as bevin points out, is not a Yorkshireman – said “sat” when he in fact said “sitting”, and I don’t suppose I’ll ever forgive myself.

*

- I’m not using the terms, high and low level, in any value-judgmental sense. Neither is more or less important in this context.

- At risk of spelling out the blindingly obvious, legislatory draughtsmen, commercial translators and technical writers may make less free with grammatic rules than may admen, blues singers and sci-fi authors.

- There are those, socio-linguists in particular, who see another of language’s functions – forging social identity – as hardly less important. This of course is highly relevant to any discussion of ‘standard’ language.

To misquote Captain Barbosa (and probably spell his name wrong – or should that be incorrectly? – into the bargain – or should that be “as well”?):

“They’re not rules as such. They be more like guidelines.”

As I recall Johnny Depp concurred. Not sure about Davy Jones though? Looking into that particular locker perhaps we could open up a treatise on other well known fictional or even real working class philosophers on the flexibility of communications channels.

I knew what was meant. And that’s the purpose of language as a communications tool – to convey meaning not to dress mutton up as lamb.

Nice one Dave – but, hey, wait a minute. You’re a Yorkshireman too! What do we know, huh?

No need to forgive yourself for anything Phil.

Seems to be a simple case of ‘nitpicking’.

Active or passive? Who cares: the meaning’s clear. And as for ‘standard ‘ or ‘sub-standard’…

Love on ya,

Jim

PS – from Yorkshire

Blimey Jim, that’s three of us blackening the good name of this cricketing county! Thanks though!!

The cat sat on the mat and remained sitting on it until it stood up whereupon it was no longer sitting but stood standing.

I remember this one from over 45 years ago and our English teacher had us all in fits of laughter at the way the English language has evolved in what is often a very nonsensical way.

When I was running I had run a long way and ran all the way without cessation. It’s a Geordie thing like gannin along the Scotswood road…to see the Blaydon races.

🙂

I should of been in that class, Susan. I’d of loved it.

The tension between language as evolving, and need for change not to be too breakneck, was perfectly expressed ten years ago by an English teacher of my acquaintance. He was complaining over a pint about a colleague who’d written in a school report that a pupil “could of done better”.

“One day”, my friend said, “that may be acceptable – but NOT YET!”

Chomsky would have known the difference between sat and sitting and stodd and standing was a chair…

Chomsky’s invaluable input was his sixties insistence that, as a discipline, linguistics was failing to acknowledge the extent of the cognitive challenge language acquisition poses. Young children use its rules, many of them to this day defying formal articulation – why does ‘big red bus’ sound right, but ‘red big bus’ sound wrong? – in highly creative ways to form unique utterances never before heard: a fact that blows crude stimulus-response models out of the water. But the near universality of such fluent creativity can easily lead ‘common sense’ observers, as it did the behaviourist linguists of the day, to underestimate what has been achieved.

One tiny aspect of language’s complexity is that words which may act as synonyms or antonyms in one syntactic context do no such thing in another. Knowing the difference between ‘sat’ and ‘sitting’ does not, I’m afraid, resolve things here.

What strikes me as funny is that Richard picks up on sat/sitting, but not on the mistaken transcription of believed as believe. You, Phil, being a bright spark naturally put believed to make the sentence grammatically coherent, despite your using the past instead of the present participle, which, as pointed out above, is a regional usage and perfectly clear.

When I saw the quote, I was sure Chomsky would have said believed and so I listened, and I think he did.

The plot thickens, Mr Chain. I saw the ‘believe’ but assumed Richard introduced the error – either by hasty copying or cut and paste then tinkering – but yours is the better interpretation, especially since you appear to have checked the transcript yourself. The original transcriber, a true Stakhanovite, may be forgiven such a mistake.

Regards as ever to Mr Ball.

PS Richard misses a trick or two. The ‘practise’ of my reply should be ‘practice’. As my teacher Miss Naylor (I’d like to say much loved teacher but, truth be told, she was as vicious a piece of work as ever terrified junior class) drilled into us, circa 1960, “noun comes before verb in the dictionary, and ‘c’ comes before ‘s’ in the alphabet.” A sound mnemonic, but one I did not heed on this occasion.

Richard also misses my “diversity from”, when I of course mean “divergence from”.

Was Richard asleep on the job? Or is Richard less pedantic than I give credit for? (I’d have been less sarcastic had Richard also addressed the more substantive content of my d’Ancona post.) Or is Richard simply, like me, a generous soul?

Are you there, Richard? You’re breaking up, man …