If therefore we hear about Hannibal having offered battle to Fabius in vain, that tells us nothing more as regards the latter than that a battle was not part of his plan, and in itself neither proves the physical nor moral superiority of Hannibal; but with respect to him the expression is still correct enough in the sense that Hannibal really wished a battle.

Carl von Clausewitz. On War, Book 4, Chapter 8: Mutual Understanding as to a Battle

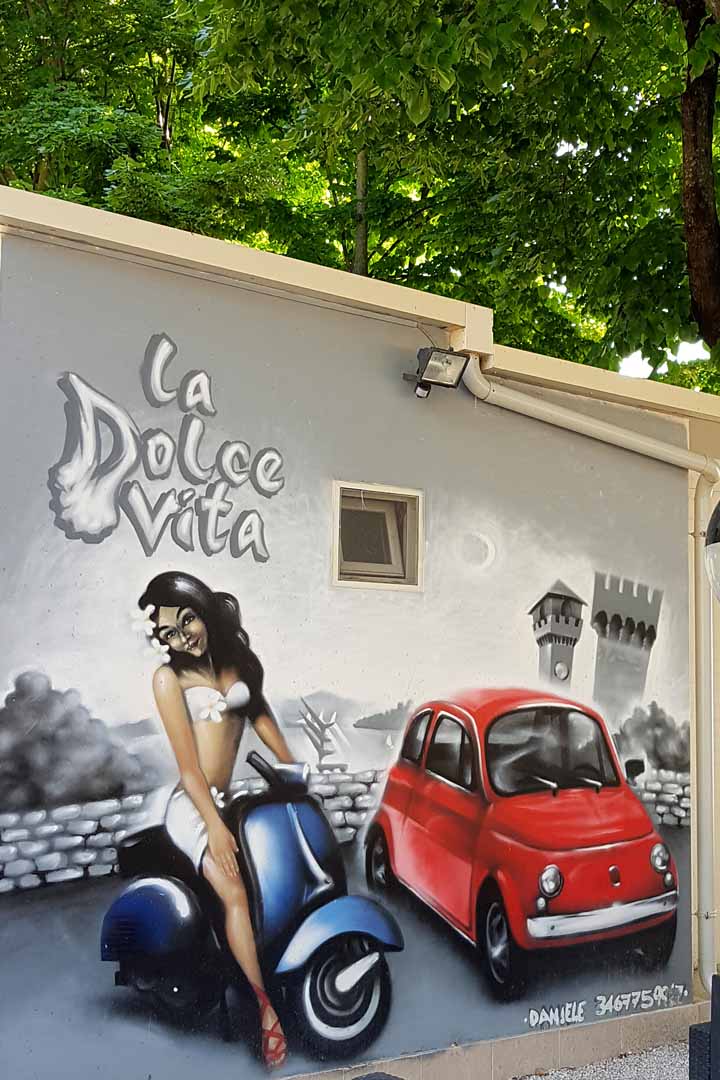

Snapped in a workaday town by Lake Trasimeno. Twas here in 217 BCE that Hannibal (often but erroneously confused with Anthony Hopkins) pulled off the largest ambush in military history, of an army 30,000 strong despatched under the command of rash Consul Flaminius to bring the Carathaginian kick-ass once and for all to heel in the Second Punic War. In the event, 15,000 of Imperial Rome’s finest were cut down in a four hour rout, with a further 6,000 captured in the mop-up. Promised safe passage home, these hapless remnants were promptly sold into slavery.

Says 19th century American military historian Theodore Dodge:

We are told nothing by the ancient authors, their knowledge of war confined to the description of battles. But it is apparent Hannibal moved by the flank past the Roman camp to taunt its general. Here is shown clear conception of the enemy’s strategic flank, with all its advantages … Nor by his maneuver had Hannibal cut himself loose from his base, though he was living on the country and independent of it; the fact is, the complete integrity of his line of communication was preserved. A more perfect case of cutting the enemy from his communications can scarcely be conceived. If Flaminius fought, it must be under morally and materially worse conditions than if his line was open; and the effect on his men of having the enemy between them and Rome could not but be disastrous.[12]

For his part, Livy, who died in CE 17, two centuries after the battle, attributes his team’s disaster less to Hannibal’s genius – though the man is widely regarded as one of the greatest military commanders in history – and more to the hot-headedness of ‘showy’ Flaminius:

Though every other person in the council advised safe rather than showy measures, that he should wait for his colleague, in order that joining their armies, they might carry on the war with united courage and counsels … Flaminius, in a fury … gave the signal for battle.

Hannibal’s come-uppance came fifteen years later in the Battle of Zama, Tunisia, at the hands of Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus with a little help from Numidian cavalry previously loyal to Hannibal. Mulling on treachery, the vast sweep of human history and – later I’d do the same at Montreuil-sur-Mer in Pas de Calais, where Field Marshall Douglas Haig set up his WW1 HQ1 – homicidal incompetence of high born fools, I strolled down to the lake on a baking afternoon to spy this wee feller, about to climb out of the water.

Note the optical effect: shadow of head and throat acting as a polariser.

But the most ubiquitous reptile – here in Umbria, close to the border with Tuscany, and later in the Dordogne – was the wall lizard. Here you see that showy green, not always apparent to the naked eye.

At the mediaeval town of Castiglione del Lago, on Trasimeno’s southern shore, I get to see why the word chiaroscuro – and its greatest exponents – had to be Italian.

A shot like this has to be taken fast, in this case on my phone. Image quality can suffer.

Butterflies everywhere.

The bulk of my time, though, was in France. Starting with the Dordogne region, and a pair of anglers on the River Isle at Périgueux.

The art of le flaneur – strolling pretty Sarlat-en-Canede, on a day of sun and nothing but blue skies …

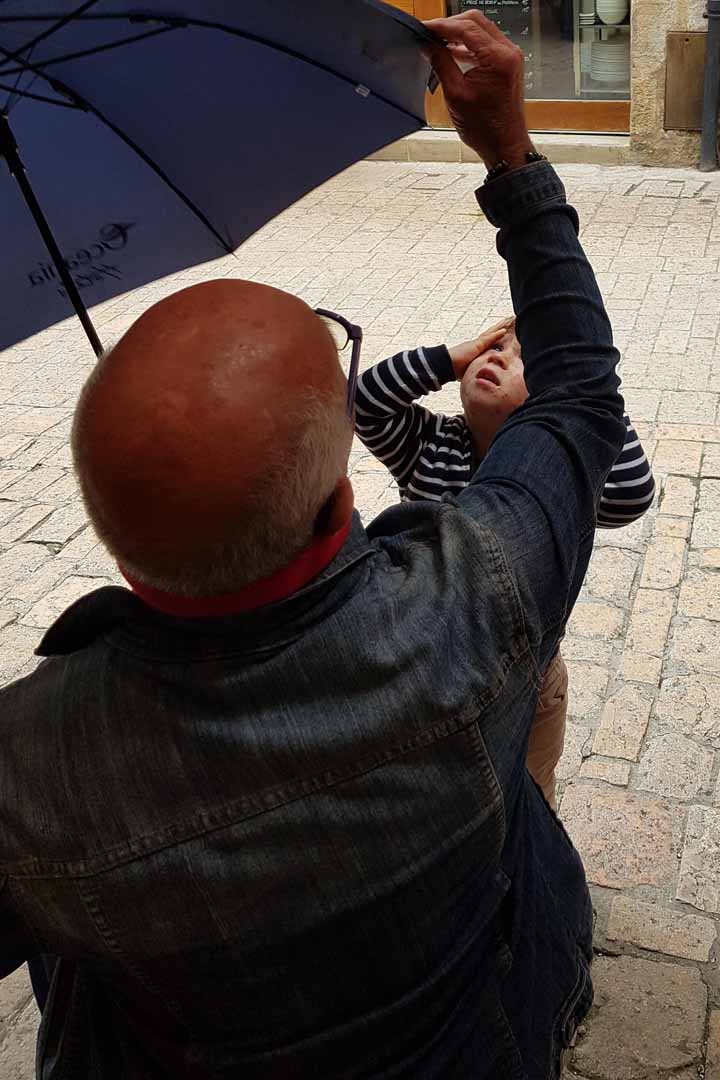

… nothing, that is, but the occasional cloudburst. When heavens open, the street snapper worth his salt is alert to the opportunities.

And while Le Badaud (The Watcher) sees all …

… le flaneur is serendipitously selective. Who set this table, and for whom? Who is the mystery woman, cigarette in hand, stood in the shadows of Malraux’s memory? Why, when les jolies femmes can’t wait to shed their kit and gaze longingly up at him, does early criminologist Gabriel Tarde look so thoroughly pissed off? Which war had reached such deadlock as to need a street name in its honour?

I first heard of foie gras, a regional speciality, in the Dennis Wheatley novels I devoured in mid teens. One of the secrets of Wheatley’s success – up there with his knowing how to stuff a page turner with just enough sex to titillate the reader without falling foul of obscenity laws yet to be challenged by the Lady Chatterly and Oz trials – lay in his frequent bouts of food porn for a UK in postwar scarcity. To the dismay of socialism’s more puritanical advocates, the working class of austerity Britain – in fact folk on the margins everywhere – lapped it up. You can go a long way to explaining the popularity of both 007 and Famous Five by reference to Bond’s deluxe taste in cigarettes and whisky and wild posh women – and to the mandatory scenes on Planet Blyton where mouthwatering pies and fruit cake are washed down with lashings of lemonade.

That said, don’t even think about eating foie gras if you’ve a scintilla of concern for animals.

I already said what I needed to say, mostly in pictures, about the Dordogne River. But here’s a pic or two from Limeuil, where the Dordogne is joined from the north east (left) by the Vezere.

The port at Limeiul once sent merlot (derived from a dark grape and named after merle, French for blackbird) downstream in shallow-draught boats to Bordeaux, and received that region’s far superior wines in the same boats, towed by human hand till the practise was outlawed in the early nineteenth century on humanitarian grounds.

We, Jackie having flown into Bergerac a few days earlier, walked up yet another ancient, steep cobbled street from the port. This lady caught my eye.

Soon we’d head northwards, by way of Lac de Vassiviere, Normandy and Pas de Calais, but that’s another story.

* * *

Nice photographs, plenty of subjects for you to focus on but where are the alps?