I know nothing that would equal the Appassionata. I could hear it played every day. Marvellous, supernatural music. When I hear it, I always think, maybe with naive, childish pride: What wonders human beings are capable of accomplishing! Lenin.

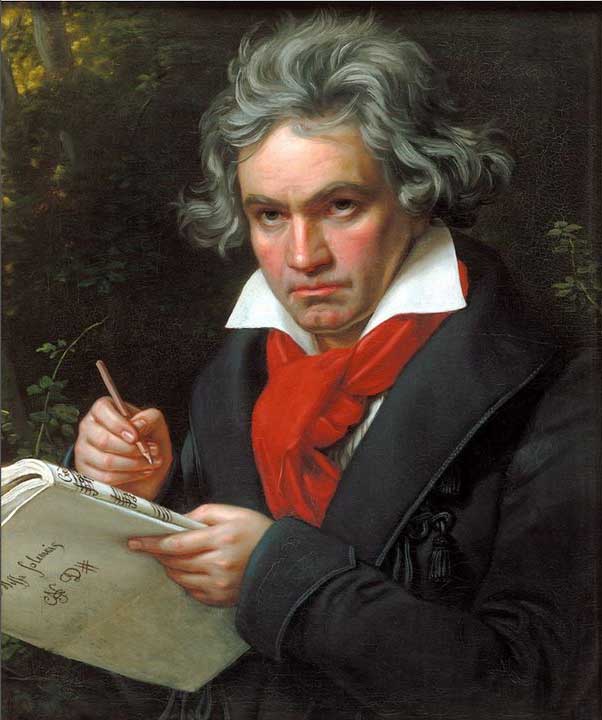

A quarter-millennium ago today, with the Americas already in the grip of revolutionary ferment and Europe on the eve of it, the man whose music would so amaze the architect of Russia’s later revolution was born in the German city of Bonn. Writing on the WSWS site, Verena Nees and Peter Schwarz tell us, in a fascinating if at times controversial 4,500-worder, why Ludwig van Beethoven still matters.

What explains the contemporary character of Beethoven’s music? Why does it fascinate people of all ages, far beyond the confines of the classical music community?

Answering this question requires that one consider the period in which Beethoven lived and struggled. Although one cannot be separated from each other, Beethoven the artist went far beyond Beethoven the person. He was the most profound musical voice during a period in which humanity progressed in quantum leaps, a period in which misanthropic cultural conceptions, according to which human beings were only capable of violence and barbarism, were refuted. His work is ineradicably connected with the striving for human liberation.

Beethoven was five years of age when the United States declared its independence, and 16 when it drafted a Constitution promoting “the general Welfare” and securing “the Blessings of Liberty.” He was 18 when the Parisian masses stormed the Bastille, setting into motion a chain of events that shook every European throne to its foundation. And he was 44 when the political restoration took hold with Napoleon Bonaparte’s defeat at Waterloo.

But Beethoven did not adapt. During the last 12 years of his life (1815–1827), he composed works that both in content and form were far ahead of their time, which broke with the conventions of the day and connected the deepest humanity with a radical desire for social change.

Georg Friedrich Wilhelm Hegel, who was born in the same year as Beethoven and heard many performances of his work, wrote of the French Revolution: “Never since the sun had stood in its firmament and the planets revolved around him had it been perceived that man’s existence centres in his head, i.e., in thought. … This was accordingly a glorious mental dawn. All thinking beings shared in the jubilation of this epoch. Emotions of a lofty character stirred men’s minds at that time; a spiritual enthusiasm thrilled through the world, as if the reconciliation between the divine and the secular was now first accomplished.”

One could characterise these lines as the motto of Beethoven’s work. He appealed to the idealism of humanity and its hope for a better world. He still inspires waging a struggle against all forms of oppression and for the realisation of freedom, to which he dedicated many of his works, such as the opera Fidelio with its “Florestan’s Aria” and “Prisoners’ Chorus” (1) and the monumental “Ode to Joy” that concludes his Ninth Symphony. (2) Today, when the capitalist system has only social inequality, dictatorship, war and destruction to offer, Beethoven’s music is enormously attractive and contemporary.

Read the full piece here …

*

Thanks for this. It brings to mind a comment by C. Wright Mills, which might equally apply to composers:

“In the absence of an adequate social science, critics and novelists, dramatists and poets have been the major, and often the only, formulators of private troubles and even of public issues”

I think Marx would have agreed.

That’s a good quote, Colin. Dickens – a master story teller and whistle-blower on the rottenness cheek to jowl with Victorian bourgeois complacency – had no coherent social theory at all.

I read once of Lenin, circa 1920, visiting an academy outside Petrograd. “And what do you read”, he asked the adoring literature students ringing him. “Do you read Proust?”

“Oh no”, they dutifully chorused. “We read [two or three suitably Bolshevik minded but now forgotten novelists]. Proust is a bourgeois!”

Lenin smiled. “Proust is better.”