David Leonhardt, New York Times, September 27, 2021

The messianic certainty I detect on all sides of the Covid conversation is dismaying. People with no obvious qualification to do so are not only sounding off in FB echo chambers as though they were leading experts, but in some cases declaring holy war on those less sure of ourselves. I’ve encountered it on all sides, but above all from the ‘sceptic’ camp. 1

Here though the crap thinking comes from elsewhere. I’ve lost two good friends to Covid. One was eighty-four, the other eighty. That doesn’t diminish the loss for those of us who loved them but, specific morbidity factors aside, age is the single most accurate predictor of Covid mortality – a statistical truth which derails the lamentable reasoning of David Leonhardt in the New York Times five days ago. Before I get to Jeremy Beckham’s careful rebuttal in Outside Voices – but not before noting that Charles Gaba is not a “health care analyst”, as Mr Leonhardt claims, but a blogger and website developer 2 – let me set out the ways in which two phenomena, A and B, may be correlated:

- A causes B

- B causes A

- A third phenomenon, C, causes both A and B

- The correlation of A with B is random coincidence

Did I miss one? I think not. Of course, reality is more complex. A and B may enhance/aggravate one another in a virtuous/vicious cycle. And to say that C causes A and B does not rule out A as an additional cause of B, or B of A.

To put it another way, I offer my list as exhaustive but not orthogonal.

But all too often we have an a priori and emotionally driven preference, often unconscious, for one explanation. Which brings me, given the anti-Trump/pro Democrat stance of the New York Times, to Jeremy Beckham’s lucid takedown of the David Leonhardt piece.

The NYT’s Partisan Tale about COVID and the Unvaccinated is Rife with Sloppy Data Analysis

The Times’ piece on “Red Covid” obscures the reality of the pandemic and manipulates data in favor of a self-congratulatory liberalism.

A widely shared article recently appeared in The New York Times’ “The Morning” newsletter titled “Red Covid,” authored by David Leonhardt. This article, presented as news reporting and not an opinion piece, argues that deaths from COVID-19 are “showing a partisan pattern,” with the worst impacts of the disease “increasingly concentrated in red America.” Given that this narrative perfectly flatters a liberal sense of superiority, it has predictably gained substantial traction on MSNBC and on Twitter.

One particular claim in the Times’ article caught my attention: that there is a clear and strong association on a county level between COVID deaths and support for Donald Trump in the 2020 election. Specifically, the article alleged that those counties which voted overwhelmingly for Donald Trump had more than a four-fold greater mortality rate than those counties which decisively voted against Trump. If true, that would indeed be a striking observation.

But, as is often the case with epidemiological observations, the question is more complicated than two variables. There are three analytic errors that can lead someone to make false conclusions from what appears to be a meaningful association between two variables: bias, confounding variables, and random statistical error. In this case, the Times’ analysis failed to discuss significant confounding variables.

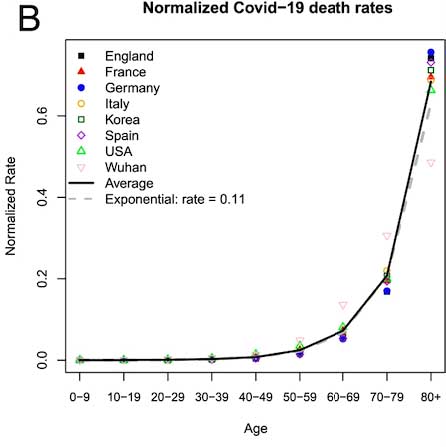

Age is a common confounder in public health research, and COVID-19 is no exception. The mortality burden of COVID-19 is not randomly distributed across age groups. Indeed, age appears to be the “strongest predictor of mortality” from COVID-19, with one’s risk of death increasing exponentially with age. According to CDC figures, the oldest populations experience a rate of death 570 times higher than that of the youngest populations. This is precisely why older populations were vaccinated first; we knew that prioritizing this population would have the most dramatic effect in curtailing hospitalizations and deaths. Yet the crude county-level analysis reported in The New York Times failed to adjust or account for age at all.

[ezcol_2third] [/ezcol_2third] [ezcol_1third_end]

[/ezcol_2third] [ezcol_1third_end]

COVID-19 Death Rates by age.

Graph from “Demographic perspectives on the mortality of COVID-19 and other epidemics,” published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, by Joshua R. Goldstein and Ronald D. Lee.[/ezcol_1third_end]

Why is it especially important that we adjust for age when comparing COVID-19 mortality rates in “red” counties with “blue” counties? Because age is not randomly distributed geographically, nor is it randomly distributed on a partisan basis. Republican voters tend to be older than Democratic voters. And rural counties, where Trump won by the largest margins, have older populations than suburban and urban counties. So this means that age is clearly a third, unaccounted for factor that is associated with both the independent variable (a county’s political affiliation) and the dependent variable (COVID-19 fatality rate) in question. This makes it a significant confounder that could easily exaggerate or distort the measured effect and lead one to spurious conclusions.

To be clear, age affects a wide range of health outcomes, and the presence of age as a confounder doesn’t necessarily preclude a subject from methodologically sound inquiry. But you do need to account for it typically by using a statistical process like age-adjusting. For instance, one study looked at seven different nations with widely different crude COVID-19 case fatality rates, ranging from 0.82% to 14.2%. However, once the study’s authors performed age-adjusting, they found that the difference in fatality rates between these countries almost evaporated. If this research technique is not feasible on the county level, perhaps because the available data is incomplete, then it’s important to explicitly state that a known confounder is a limiting factor in extrapolating the significance of your research, so that the reader knows to take the findings with a grain of salt.

Another way researchers try to tease apart a confounder from the variable being investigated is looking only at data where the distorting effect of the confounder is not present. We could do something similar for this research question. Take my home state of Utah, for example. Utah is a very red state. Trump won Utah by more than 20 points in 2020. But Utah also has the youngest population in the country, with a median age of approximately 31 years old. If partisan affiliation were a significant factor that explains deaths from COVID, we would expect Utah to have a greater COVID death rate than the national average, and the younger population helps us minimize the effect of this confounder. But instead, what we find is that Utah ranks 45th in the nation for COVID deaths, with 91 deaths per 100,000 population, far below the national average of 210 deaths per 100,000. This suggests (without proving) that age, not partisan affiliation or ideology, is paramount.

And all of this only accounts for one potential confounder (age). There are other potential confounders that should be addressed. For instance, the disparity in health outcomes between rural and urban populations likely means that people in counties that voted heavily for Trump have other comorbidities that place them at greater risk of death from COVID-19. And people who live in rural areas also experience significant disparities in health care access, with higher rates of uninsured, diminishing available health care facilities, and longer travel times to the nearest hospital. In the past decade, 138 rural inpatient hospitals have closed. This unjust inequity that persists in rural America has previously been a matter of persistent concern for writers at The New York Times, even in the context of reporting on COVID-19 when the pandemic was in its early stages.

To be clear: there is no question that COVID-19 vaccines are a safe, effective, important tool in protecting people from severe disease and death.3 The vaccination rate for rural counties is 41.4%, while the rate in urban areas is 53.3%. This difference also surely has an impact on the different rates of death from COVID-19. But this is only one part of the equation, and The New York Times’ recent viral article contained no such nuanced or informative discussion about this complex web of interrelated factors influencing disease burden and health outcomes. If you search the article for any mention of ‘age,’ or ‘rural’ you get no results, because these factors didn’t appear in their analysis at all. In any discussion about factors influencing COVID-19 mortality rates, failing to mention the role of these important demographic influences is journalistic malpractice that grossly distorts reality.

So if it failed to account for any of these factors, how did The New York Times ultimately account for the higher death rate in Trump/rural counties? It does so entirely by invoking the ideological makeup of their knuckle-dragging residents and their apparent self-destructive desire to “own the left.” Under the subheading “Why is this happening?”, The New York Times asserts the following:

What distinguishes the U.S. is a conservative party — the Republican Party — that has grown hostile to science and empirical evidence in recent decades. A conservative media complex, including Fox News, Sinclair Broadcast Group and various online outlets, echoes and amplifies this hostility. Trump took the conspiratorial thinking to a new level, but he did not create it. “With very little resistance from party leaders,” my colleague Lisa Lerer wrote this summer, many Republicans “have elevated falsehoods and doubts about vaccinations from the fringes of American life to the center of our political conversation.”

Part of the problem is that The New York Times relied on incredibly shaky source material. Much of the article is based on writings of an individual named Charles Gaba, who appears to be a web designer and “internet consultant.” Gaba runs a Patreon page where he disseminates his writings to subscribers, which are not submitted to reputable peer-reviewed publications. But this lack of rigorous scientific review was no barrier for The New York Times relying on his “findings,” even as the Paper of Record in the same breath scolds those who it says remain “hostile to science and empirical evidence.”

The irony is thick indeed, and the reason why should be obvious: even if the methodology is unsound, the findings fit a preferred narrative that the overwhelmingly liberal readers of The New York Times want to hear. If Gaba’s blog had made the opposite claim – if it had focused on counties like those in Utah, for instance – I think it’s safe to say it would have never seen publication in The New York Times. For this paper, it appears that feeding its readers’ desire to feel intellectually and morally superior to “Red America” is of utmost importance, even if it comes at the expense of accurately reporting on the complex reality of the COVID-19 pandemic.

We may not be better informed, but at least we know who to hate.

Jeremy Beckham, MPH, MPA, is a Utah resident who writes on matters related to science, politics, and animal rights.

*

- I don’t say all Covid sceptics are chat room professors. Indeed, I have drawn attention to marginalised voices I say have to be taken seriously – here for instance.

- In principle, being a blogger/web developer does not preclude being a health care analyst. In the real world, however, for the NYT to present the former as the latter is either duplicitous or lazy. Citing non experts – or with equal mendacity, experts in a different discipline – as experts on the central issue has grim form. Ask the mothers, already grief stricken, given life sentences after paediatrician and expert witness for the prosecution Roy Meadow assumed statistical authority by wrongly – his errors are summarised here – calling the odds of losing more than one child to cot death at seventy-three million to one.

- Jeremy Beckham’s claim that Covid vaccines are safe has stirred a predictable hornets’ nest below the line. Some say it is false, others that it is true, yet others that he need not have made such a disclaimer. FWIW – which, statistically speaking, is near zilch – I had two shots of AstraZeneca with no ill effects beyond continuing to piss people off on this as on other matters.