Is Facebook’s Frances Haugen a whistleblower? Clearly not in the sense that Julian Assange and Chelsea Manning, Daniel Halesworth and Katharine Gun are. But is there any sense in which she can be said to be one?

A month ago in a piece headed, Haugen isn’t really a ‘Facebook whistleblower’ – and it’s dangerous to imagine she is, Jonathan Cook wrote that:

[Frances] Haugen has indeed used her position as a former employee in a hyper-powerful corporation … to bring to light things that were supposed to be hidden from us.

That meets most people’s basic definition of a whistleblower.

But whistleblowers are taking on institutions far more powerful than they are. Those institutions will fight back in the dirtiest ways when their core interests are under threat. Whistleblowers typically face a cost for what they do …

That is evident in the treatment of the bravest whistleblowers. Some are prosecuted, jailed and near-bankrupted (Chelsea Manning, John Kiriakou, 1 Craig Murray), others driven into exile (Edward Snowden), while the unluckiest are vilified and disappeared into the modern equivalent of a deep, dark dungeon (Julian Assange).

In just two decades social media platforms have made a few men ludicrously rich. This on top of two preceding decades of bullish neoliberalism whose soaring inequality no one seemed able to stop. While ‘trickledown’ apologists defending such inequality were proved wrong long ago by big data and the means to crunch it, no agency had the capacity – such is the power accruing to extraordinary wealth, and such the nature of capital’s stubbornly amoral logic – to call time.

As well as being economically dysfunctional 2 and a moral affront, such inequality is profoundly antithetical to any meaningful democracy. Before we even get to the special case of media, old or new, the concentration in ever fewer hands of private and by that fact unaccountable wealth – i.e. power – is as evident in a Gates, Bezos or Soros as in a Zuckerberg or Murdoch.

Social media have also changed beyond measure the ways we live. “Platforms” is too trifling a word. These cyber-realms wherein we spend so much of our lives have for many of us rivalled or even usurped earlier means of meeting our human need, affective as much as instrumental, for communion.

For community.

And they are changing the way we consume news and ‘expert’ views of the world. This might compromise – for now I put it no stronger – the ability of established power to define what is, and what is not, acceptable political opinion. That many-to-many model is by definition unruly. In social media the seeds of challenge – to understandings, dominant but mostly unspoken, of which discourses are ‘moderate’ and which ‘extreme’ – may take root. 3

Though this threat to power remains just that – a potential – we can gain at one stage removed a sense of its seriousness from Chomsky’s remarks on older media:

The smart way to keep people passive and obedient is to strictly limit the spectrum of acceptable opinion, but allow very lively debate within that spectrum — even encourage the more critical and dissident views. That gives people the sense there’s free thinking going on, while all the time the presuppositions of the system are being reinforced by the limits put on the range of debate.

But the media Chomsky had in mind, having played a key role for two centuries in defining that spectrum of acceptable opinion – also known as the Overton Window 4 – are now fighting rear-guard actions on three fronts,

- Their two hundred year old business model is under threat because a monopoly grip afforded by high capital entry barriers (presses and broadcasting technologies, and reliable distribution networks) has been eroded by the plummeting costs of internet publishing and of the means of capturing/creating and uploading high quality audio-visual information. At the same time, another high capital requirement, employing in situ foreign correspondents, is giving way to news syndicates, citizen journalism and budget cuts. This is not to say those traditional media are out for the count. They still reach audiences greater than those of any blogger or vlogger. (Which is why Julian and Wikileaks took the risk of approaching the Guardian with that vast cache of evidence of war crimes on the assumption, horribly misguided, that this bastion of liberal values would act in good faith and with courage.) Nevertheless, their grip is not – see bullet three – what it was.

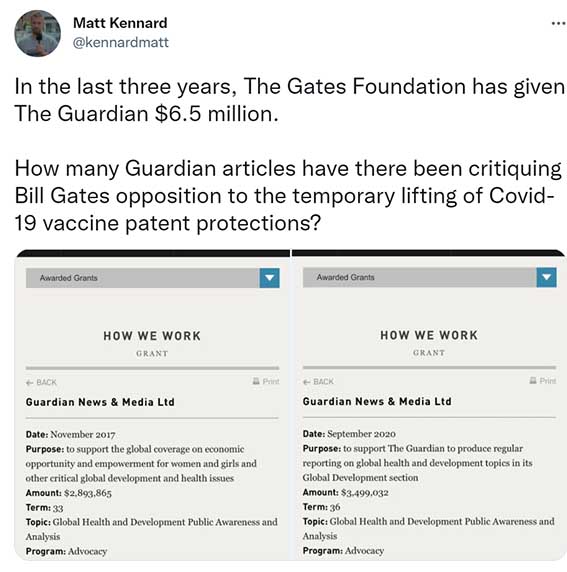

- Worse still for media monopolies, the model’s revenue streams – one part purchase price, two parts advertising – are both drying up. Who buys a paper these days? As for the other and larger income stream, a Guardian now reliant on donors like Mr Gates …

… attests to the reality of ‘media buyers’ (a Madison Avenue term speaking truer than it knows) not coming online with the sums once hoped for; rather, sensing more bangs per buck in sponsorship and celebrity endorsement. 5

(Media dependence on advertising barely registered with consumers. Our eyes were on the tangibles of purchase price, subscription fees and licence costs. Social media on the other hand, once the subscription model of Friends Reunited had been left in the dust, begged the question: why are those nice folk at FB and Twitter so generous? But few gave it more than a moment’s idle thought. It’s not in human nature – at least, not under the consumer capitalism we grew up with – to look gift horses in the mouth. It fell to piss-vinegars like Yours T. to intone with crushing futility the old saw of there being no such thing as a free lunch, and the more recent one that if the product is free, the product is you. )

- Finally, trust in corporate media is in measurable decline. To be sure, we must factor in that what people say – and what they think and do – aren’t always the same. So in assessing this claim in the Forbes piece just linked to …

… for the first time, Edelman’s annual trust barometer … revealed that fewer than half of Americans acknowledge any kind of trust in the mainstream media …

… we should remember that many of us think propaganda, with advertising merely its most blatant form, “works on others but not on me”.

(Even as we profess, in all sincerity, our distrust of corporate media, they continue to shape – if we have not time or inclination to triangulate a wide range of alternatives – our understandings of the world in ways which favour power. I’ve seen this play out in my own thinking and in interactions – back in the day it was the 6 Counties and USSR; now it’s Syria, Russia, China – with friends whose grasp of corporate media’s systemic unreliability may be sophisticated, but is insufficiently resilient to propaganda blitzes on issues critical to ruling class interests.)

Nevertheless, since Edelman is reporting a relative not an absolute, the year on year trend recorded in its findings cannot be ignored. That social media, and internet in general, have unquestionably contributed to the decline points us to the truth that all these factors interact in mutually reinforcing ways.

*

Bear with me a moment. It’s time for a little chat about ideology.

This, in the sense social scientists use the term, is as pervasive as the air around us – and about as visible. 6 It’s a mesh of fiendish complexity, woven from materials too fine for casual gaze to discern. It shapes, funnels and filters. It sets limits on what we can even imagine. As such it may be likened to a chemical in our water supply (with the question of who benefits easier than that of who put it there) or an invisible, odourless gas pumped into the air we needs must inhale.

But I like the mesh metaphor, reflected in counter-cultural appropriation of another term, a nod to Lana Wachowski’s sci fi dystopia of the same name. The matrix.

Ideology is negotiated, affirmed, reaffirmed and continually micro-adjusted through myriads of interactions – the trifling and the monumental, the casual and the ritual – in daily life. So deft are its shifts, so intuitively flexible the sway of its adaptive hegemony, that the descriptor more widely used than any other is common sense.

Yet my use of the term, hegemony, is not fanciful. This thought-matrix does not come into being by chance, as a net weltanschauung arrived at by social actors engaging more or less randomly as sole and equally empowered agents.

And in so doing, negotiating and renegotiating as peers the nature of reality and truth.

Rather, as in the movie but with vastly more depth and intricacy, ideology in a capitalist world is lived, breathed and given constant renewal within relations of socio-economic power largely hidden. Hidden by what? By surface forms of Western Democracy, and of markets in which free people choose to interact as labour-sellers and consumers, and where no aspect of the human experience remains unmonetised for want of trying. 7

I’m tellin’ myself I found true happiness

That I’ve still got a dream that hasn’t been repossessed

Bob Dylan

(You’ll doubtless recall assenting to that Monetising of Everything on one or more of your twice a decade pilgrimages to the polling station.)

The ruling ideas of any age, Marx told us, are those of its ruling class. Which under capitalism is to say that seemingly immutable facts of life – private and increasingly monopolistic ownership of wealth creation … someone having to foot the bill for social expenditure … a law of supply and demand well able to explain the movement of commodity prices; but not price itself – just happen to serve the most powerful interests on the planet. Understanding this is a huge part of any convincing answer to the question, otherwise unfathomable: why do turkeys vote for Xmas?

And why do morally upstanding individuals, in the face of evil, take refuge in an impartiality at best delusional? We can’t have it both ways. Is we or isn’t we empowered by democracy?

It is impossible to capture in a few paragraphs the depth and subtlety of a concept pioneered from his prison cell by the Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci, and on which theorists of diverse political stripe have subsequently built entire careers. I aim only to hint at the profound but elusive nature of ideology, and to insist that assumptions of mass media “telling us what to think” are too simplistic.

But that’s just me paying my dues. Such ‘simplistic’ assumptions don’t begin to rival, on sheer naivety, a more widespread failure to see the grip of media – privately owned and answerable to private interests – on the sense we make of the world. Like pompous bores who brag of their ‘immunity’ to advertising, and thereby parade a stupefying lack of awareness, those who deny media’s systemic negation of informed consent, hence of democracy itself, 8 walk the talk of the blissfully obtuse.

Not for nothing were our media dubbed the fourth estate. They are an indispensable element in any explanation of how the truth, so easily affirmed both logically and empirically, of rule by and for the few is kept from view by an Overton Windowframe whose function is to maintain the fiction of rule by and for the many.

(Though I don’t doubt that most journalists sincerely – if self-servingly – believe otherwise. The trappings of an open society and freedom of speech, the nature of ideology as discussed here, and the many examples of inconvenient revelations on secondary but still important matters, all sufficiently cloud the waters to allow those journalists to believe their first loyalty is to truth and not to power. And as I’ve said before, journalists who know what’s good for them please editors. Editors who know what’s good for them please proprietors. And proprietors not only crave honours and a place at the high table. More fundamentally, they need advertisers and/or wealthy donors.)

A corollary being that if the media business model fails, a capitalist ruling class must find some other to take up the mantle. And what could that ‘some other’ possibly be, if not social media?

Hold that thought. We are almost ready to return to Jonathan Cook and the question of whether Facebook’s Frances Haugen is a whistleblower. First though, I should summarise the similarities and dissimilarities between traditional and new media. It needn’t take long.

What they have in common:

- Both are channels of information, opinion and entertainment.

- Both are privately owned. In the case of social media even more than in older media, a few immensely rich individuals and corporations profit from monopoly ownership.

- Both make those profits by selling audience/user data to other for-profit concerns.

- Both act as gatekeepers of knowledge and upholders of the Overton Window. This is more obvious and direct with traditional media. And more subtle and diffuse with social media whose controls are those of preferential algorithms and ‘responsible’ policing – too light touch for many – rather than the absolutism of editorial control over content.

That last points to the major difference. Traditional media have a one-to-many communication model, social media a many-to-many model. The latter led some to welcome their potentially democratising role. That potential still exists, but is painfully restricted by prevailing ideology. Not to put too fine a point on it, the turkeys who vote for Xmas have a greater online presence than the half-ways awake.

Well that was inevitable: hence my foray into ideology. But now we see calls for bringing social media under tighter control. As always when civil liberties are about to be reined in, the inroads are made in the name not of curbing freedoms but of combating wickedness.

As always the calls appear to come not from on high but from ordinary folk; most pressingly in this case from parents rightly concerned at the many and real evils online.

And as always the calls are orchestrated and used by those with a different agenda. What might that be? Restoring control, given that slow but unmistakeable decline of traditional media, over:

an Overton Window whose function is to maintain the fiction of rule by and for the many

Now we’re ready for a return to Ms Haugen and that Jonathan Cook piece. With all the heavy lifting done, I can promise brevity. In fact I shan’t say another word.

We might go so far as to argue that, as a rule of thumb, the more severe the penalty faced by a whistleblower, the greater the threat they pose in bringing to light what is supposed to remain forever in the dark.

One problem with thinking of Haugen as a whistleblower is that it is far from clear that she has paid – or will pay – any kind of price for her disclosures.

And maybe more to the point, it seems that when she turned to 60 Minutes to help her “blow the whistle” on Facebook she knew she would have powerful allies – right up to those occupying the White House – offering her protection from any meaningful fallout from Facebook.

If reports are to be believed, she has already been signed up with the public relations firm that has represented Jen Psaki, the White House spokeswoman …

A proper whistleblower is trying to reveal the secrets of the most powerful … [to] expose crimes and misdemeanours by the state, by corporations and by major organisations so that we can hold them to account, so that we, the people, can be empowered, and so that our increasingly hollow democracies gain a little more democratic substance.

But Haugen has done something different. Or at least she has been coopted, willingly or not, by those averse to accountability, to the empowerment of ordinary people …

The establishment, in fact any major organisation, is likely to have at least two major competing groups within it, unless it is entirely authoritarian. (Even then, leaders of dictatorial regimes have to worry about plots and coups.)

There are rival visions of what the organisation – or state – should do, how best to manage its interests and maximise its success or profits, and how best to shield it from scrutiny or reform. Those inside the organisation are united in their motivation to maintain their power, but they are often divided over how that can best be achieved.

In western societies, these opposing visions typically revolve around ideas associated with liberal and conservative values. In the case of states, that simple binary is often reinforced by electoral systems that encourage two parties, two political choices, two sets of values: Democrats versus Republicans; Labour versus Conservatives; and so on.

It is part of the establishment’s success – the way it preserves its power – that it can present these two choices as meaningful. [my emphasis]

But in reality, both support the status quo. Whichever party you vote for, you are voting for the same ideological system – currently a neoliberal version of capitalism. However you vote, the same elites stay in power, with the same kinds of corporation funding them, the same revolving door between the political, media and business establishments.

So how does this relate to Haugen?

Our “Facebook whistleblower” is not helping to blow the whistle on the character of the power structure itself, or its concealed crimes, or its democratic deficit, as Manning and Snowden did.

She has not turned her back on the establishment and revealed its darkest secrets. She has simply shifted allegiances within the establishment, making new alliances in the constantly shifting battles between elites for dominance.

Which is precisely why she has been treated with such reverence by the 60 Minutes programme and other “liberal” corporate media and feted by Democratic party politicians. She has aided their elite faction over a rival elite faction.

Manning and Snowden challenged the very basis on which our societies are organised. They hurled a big rock into the placid lake that is the ideological background to our lives.

* * *

- Mr Kiriakou is the least known of those listed by Jonathan Cook. CIA analyst and case officer, senior investigator for the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and counter-terrorism consultant to ABC News, he was the first US government official to reveal that waterboarding, which he called torture, was used on al-Qaeda suspects. For this he was in 2013 handed a thirty month jail sentence. The outcomes for Ms Haugen have been less exacting. This gushing potted hagiography lets us know she is “a talented and beautiful data scientist”. Which is a weight off my mind, though more reassuring still is that a net ‘worth’ put by said hagiography at $2-3 million will not only remain intact, but in all likelihood increase as a result of her brand of whistleblowing.

- Inequality as economically dysfunctional? Before we get to men like Gates and Soros bypassing critical oversight in the arena of social policy, as explored in this piece, the levels of inequality now existing are indefensible on purely practical grounds. Trillions were pumped into corporate coffers by Barack Obama’s quantitative easing program. The mega rich do not put that money back into the real economy. Where low income groups have no choice but to spend, extreme wealth will buy another Picasso or two and, more importantly, further fuel financialised ‘casino capitalism’ through increased rentier holdings. Did QE work? Yes it did, and that alone gives the lie to the intuitively comforting but economically illiterate analogies, with household budgeting, spun by monetarism. (States with fiat currencies do not tax and borrow to spend. They issue money as needed – with ‘need’ defined by politicians answerable not to you and me but to Capital – and use taxation to keep inflation in check.) But did it work efficiently? Absolutely not. To give just one example, the difficulty for first time house buyers of getting a mortgage – those toxic sub-prime bundles having triggered the 2008 crash – has sent rents soaring and made a seemingly endless bull market of the wholly non productive buy-to-let sector. Debt forgiveness for the people would have achieved so much more. But that – witness Mr Obama’s reminder to the bankers that he stood “between you and the pitchforks” – is hardly the point.

- Capitalism ‘s response to falling profit rates will be further cuts, casualisation, curbs on already enfeebled unions to reduce the share of net wealth going to labour, war (for resources, markets and to thwart China rising) and deprioritising of environmental measures. In these circumstances discontent is inevitable. We can speak of greed but this is the irreducible nature of capitalism. Were we less enthralled by the folderol of a largely illusory democracy, it would go without saying that greater repression and/or deception will be needed: the reining in of social media absolutely included.

- The meaning of the Overton Window has widened. Once a narrow technical concept by which policy wonks and party election managers might gauge how far they could push, at any given time, socio-economic change, it now encapsulates the wider sense of Chomsky’s spectrum of acceptable opinion.

- State media like the BBC are subject to all of these pressures and dependencies, just less directly. The Beeb relies on licence fees set by politicians who themselves fear the editorial fulminations of the Mail, and/or are in bed with Murdoch et al.

- There’s another sense in which the term ‘ideology’ is used: to accuse a person of bias arising from a specific set of opinions almost always counter to dominant narratives: “oh well, he’s just spouting communist ideology …” Needless to say, I’m not using the i-word in this crude and limited sense, for which smaller words like ‘bias’ suffice.

- Do you recall making the ‘choice’ to acquire the means of subsistence by selling your labour under contracts of employment which bely the coercions – their history, trust me, is soaked in blood – which brought you to the fiction of a pact between equally empowered parties? In Russia’s chaotic Yeltsin era I remember reading with delight of a borrower who, prior to returning his signed loan agreement to the bank, substituted the latter’s interest rate with one of 0%. That the bank sought nullification in court, once it realised, gave the lie to the myth of a covenant entered into by peers. (Since the bank lost, I’d have been overjoyed had he inserted a negative rate.) I’ve now and again idly speculated, in the course of my ongoing battle with Sheffield Hallam Uni – its ninth birthday next month – whether HR would have spotted my pulling a similar stroke with the zero hour contract I signed and returned in 2006.

- ” … systemic negation of informed consent, hence of democracy itself …” – in Britain decides, written after that country’s May local elections upped the control of serial liar Boris Johnson’s corrupt and inept party, I wrote: “I can think of no more cogent argument for insisting that Western democracy is 95% bogus than that (a) democracy implies consent, (b) consent is meaningless if uninformed, (c) informed consent implies truly independent media. That last we do not have when our media are large corporations selling privileged audiences to other large corporations’.