.

Stats nerds and propellor-heads aside, humans are crap at probability. 1 It’s not that we can’t do sums. Weaving the lanes of a crowded M1 at 70mph, cutting a zig-zag across a busy junction on foot or leaping for a cricket ball, we effortlessly make complex appraisals of speed, vector and angle. And we do so intuitively, seldom erring.

That’s likely because we’ve been making those calculations for 100,000 years or so, hurling flint spears at woolly mammoths and legging it from sabre toothed tigers. With all that evolutionary wind in our sails, we’re pretty good at this kind of thing.

But only in recent decades have we been called upon to make assessments of probability which draw on large and by that fact abstract data sets. Our ineptitude here is telling. As is the flaky reasoning we come out with if we aren’t expensively educated; else push down to netherworlds of the brain stem if we are.

Everybody knows a bloke down the pub who knows a bloke down some other pub whose Uncle Sid smoked eighty a day and died aged ninety-eight while shagging Auntie Ethel, or whose fifth cousin thrice removed’s hairdresser was the sole survivor of a motorway collision – not despite but because she hadn’t been wearing a seat belt.

I’d hate to be unduly reductive. When these and other such tales are being traded and trumped, there’s usually more than one engine doing the pushing and pulling:

- we’re gonna smoke anyway, or make that two minute drive to the offie without the faff of fastening in, but feel obliged to put up a show of intellectual justification;

- we love counterintuitives; a gleeful fuck you to the tyranny of accepted wisdom;

- AND we’re crap at probability.

Park that thought. I’ll be back, though I may be a while.

*

I don’t say the nurse in green – all rubber gloves, cap and gown – is smirking. How would I know? She’s masked up for covid. But to my wary eye she’s a far cry from not smirking. That glinting of the eye, as she points to the couch, telegraphs gallows humour long before her words are out:

“Go on. You know you want to!”

I’ve been in the cystoscopy room fifteen minutes without so much as loosening my belt, far less unsnapping my 501s. Meeting her gaze, I respond in kind.

“No thanks. You’re all going to pounce on me and stick things up my willy.”

All? A cystoscopy requires three hands on dick deck: one to secure the object at the epicentre of things – limp, forlorn and shrinking in vain to absent itself – as two others thread a narrow tube (how narrow?) along nerve-rich pipework whose owner’s sole protection from pain (though not indignity) is a numbing gel, syringed like cake icing into the orifice of inordinate sensitivity.

In, in and thrice in!

In further!!

In all the way, passing the prostate (worst part, I’ve gathered, in the face of strong competition from other anatomical hot spots) till the miniature spy-cam at the business end has defeated gravity, decorum and other spheres of resistance too hair-raising to dwell upon, and snaked its insanely invasive way into the bladder to snap away like David Bailey.

Nobody has three hands. Even without the high likelihood of a fourth being needed to soothe or slap the patient into line, it takes three people – two cystoscopers and one cystoscopee – to do this particular tango.

So why do I – no maths wizard but in the top half of the class on mental arithmetic – count four of us in the room?

*

Seventeen days earlier. A Saturday morning in late November sees me in a line stretching out of my GP’s surgery and curving around the staff car park. We’re waiting for our third covid jab and, in my case, the standard flu shot I should have arranged months ago. The procedure honed with military precision, I’m through the surgery door within five minutes and baring each arm in turn within ten.

I’m told to stay a further ten in the waiting room before buggering off, in case I have an adverse reaction. I give it five. For the next few hours I feel like somebody punched me in each bicep but am otherwise fine. Then I start peeing blood.

To be clear: I don’t say either of the jabs, and what clinicians call gross haematuria, are causally linked. But I’d have to be one of them there coincidence theorists to rule it out, wouldn’t I? 2

On Sunday the flow is dark crimson but now I see – and feel – flocculent clots passing through, like fine tufts of cotton wool. That’s a tad scary. Ten years ago I spent four catheterised days on a hospital ward, an experience I’ll be returning to before I’m done, because they weren’t going to send me home until my pee ran pale golden clear, with no danger of post biopsy blood clots blocking the urethra.

Scary or no, on Monday morning I drive up to Sheffield for a date with an electrician. But as it turns out, destiny has other ideas. After coffee in Sainsbury’s just after nine, I heed the call to point percy at the porcelaine. Only to find I can’t emit a drop.

Things just took an alarming turn for the worse.

I’ll pass over much of the day’s horror. I get myself to a nearby walk-in. (It’s crowded of course, and grossly understaffed so we’ll welcome with open arms the shining knight of privatisation.) My experience of NHS walk-in clinics is that when you finally do see a medic, you usually get good care from someone who may be visibly exhausted but is not too far gone to hear you out.

Boy, do you have to wait though!

By the time I see a nurse it’s four pm. I haven’t peed since getting into my car at seven-thirty for the drive up the M1 – though I’ve sat on a succession of pub loos, for upwards of half an hour at a time, my reward a few bloody droplets. Ordinarily the very idea of the catheter inspires shock and awe, fear and loathing. 3

Now I’d kill for it.

She can’t oblige – ‘we don’t have the kit here’ – but is kindly and decisive. As I pace her domain, slowly leaking into my jeans – beyond embarrassment but gaining scant relief from the single drop seepage, every other minute, through blood clots I assume to be impeding the flow – she calls Urology at the Royal Hallamshire to secure, with no small firmness on her part, a promise that I’ll be seen on arrival. Leading me back to reception she has the lady call a taxi. Have I the money for the fare? Provided they’ll take plastic, I tell her.

She turns again to phone lady. ‘Put it on my account.’

*

It’s rush hour. The taxi is late. Nor am I seen right away, though Nurse Walk-in got ten out of ten for effort and persuasive skills. As I pace the waiting area like a defective robot, I hear a bellow from an adjoining room. Startled out of my own vanishingly small perspective, I read it as work-place joshing of the kind familiar to me from salad days on shop floor and building site. Then I hear it again. Hypothesis refuted. There’s no-one larking around here. Depend on it: yon side of that door some CIA goon, muttering darkly, is subjecting a man to enhanced interrogation.

Or to the dreaded catheter. Yes, that’ll be it. Hence that third voice, soothingly female.

I bet the ladies slide it in with greater care. But does the recipient ever get a hard-on?

Highly unlikely, I decide. All things considered.

The cries continue for a minute or so, then I hear a very different but equally involuntary sound; barely distinguishable from that moan of beatific surrender in the aftermath of an exceptionally powerful orgasm. It’s followed by the voice, now recognisable to me, of the male nurse who’d greeted my arrival:

There you go. Wasn’t that worth all we’ve had to put you through?

Soon be my turn, I tell myself. And you know what? For all I’m a total jelly-baby when it comes to pain, right now I can’t wait. Bring it on!

*

Half an hour later, I’m still pacing. The nurse of rough but kindly manner appears. He opens an examination room door, addresses me by name and bids me enter.

In you go, Philip

At last! But no, he leaves me alone in that room. I’m there the best part of an hour, sitting on its couch, jeans at thigh level not because I’ve been so instructed but to lessen, if only by seconds, whatever further delays I must endure.

My boxers stay for now in situ; sodden, but I have a card up my sleeve. Anticipating this sorry state of affairs while walkin’ to the walk-in, I’d nipped into Primark for boxers and cheap jeans. Nestled in a paper carrier bag at my feet, they too await their moment.

It occurs to me that my man had clocked the way I’d paced that waiting area, legs knotted as I stared balefully down at my crotch. Even at thirty drips to the hour, I’d hit the limits of denim’s capacity to absorb body or any other kind of fluid. In other circs I’d have been watching the lino at my feet for the first pooling signs of final humiliation. Now such trivialities count for nothing.

They can catheter me starkers on a floodlit stage. Just let it be now!

All the same, I reckon I’ve been put here not because anyone remotely competent is remotely ready to see me, but to spare my dented dignity. Or others’ sensitivities. Or the waiting room floor. Or all three.

At long last my man returns to hear my story. I’m not too far gone to register his swift dismissal, in our polarised times, of any link between current plight and those Saturday morning jabs. But I don’t press the point. I crave deliverance, not debate.

He rules out the catheter. The clots, it seems, place that on the wrong side of iffy. The risk is of compacting rather than piercing the blockage. I’m close to tears. So what now?

I’ll see what the doctor says, but what we really need from you is a urine sample. 4

Jeez – if I could give you that I wouldn’t be here, would I? But I keep such unhelpful commentary to myself. Call it Stockholm Syndrome but I’ve warmed to this guy. And my instincts tell me, as they had with Nurse Walk-In – she of the taxi budget – I’m in good hands.

*

Fifteen minutes after Nurse No Catheter’s exit for doctor’s orders, the miracle happens. Without warning I sense the dam breaking and leap to my feet. The loo is out of the question but in one corner, a single step from the couch, is a washbasin. I’m there in a nanosecond, front of boxers shoved down in readiness.

I’ll use the washbasin if I have to but, mindful of what nurse said, I eyeball the room. Zilch. But what’s this? On a window ledge above the basin, within arm’s reach, sits a single instantiation of those grey cardboard containers designed for this very purpose. It’s chocka with clinical bric-a-brac but a flick of the wrist upturns it. Even as its erstwhile occupants – sealed syringes I think – are spinning across the sill and onto the floor, I’m holding it above the washbasin with my left hand while my right aims a dark red torrent to fill it to the brim. I can’t be sure I wasn’t actually weeping with joy: tears of gratitude to who knows what?

Sweet goddess of bounteous urination, hallowed be thy name!

The bliss of bladder release, I discover, can sweep aside modesty and decorum as effectively as the agonies and apprehensions of blockage. With container and contents nestling in the wash-basin, I pull up boxers and jeans, fling open the door and go dancing out.

I must cut a wretched figure. Damp denim bunched in fist to forestall downward slide, I scan the waiting area. A few blokes escorted by a wife or two barely register. Through an open doorway at twenty paces I spy my man shooting the breeze with colleagues.

Hey! I got you a sample!

Pause.

And it’s got blood clots in it!

Too much information for so public a space? Am I bovvered? The nurse, to his undying credit, comes running. Back in the room of relative privacy he draws a syringeful, then turns to me.

You’ll be thrilled to know this is old blood. Look at it! It’s more rust coloured than red. The source of all this, wherever it is, has stopped bleeding.

Sod’s law, innit? Now that I can wait in serenity – wet denim, where is thy sting? – I don’t have to. As Nurse No Catheter leaves with sample, a young woman enters. Peering over her covid mask she introduces herself as a student nurse and asks if I mind answering a few questions.

*

I take her through the chain of events set out above, adding that ten years ago I had a prostate scare. Reporting to my GP, back in 2011, that I needed to pee more often and the flow was not what it had been, I’d been referred to this very hospital. This very department in fact.

Over several visits I’d lost count of the times I’d had a DRE – not the rapper – and on three of them had biopsical darts fired up my bum to snatch samples of prostate tissue.

(I never saw the gun. They didn’t offer, I didn’t ask, and my eyes weren’t the part of me turned towards it. But in my mind’s eye I saw it as one of those kids’ toys that fire corks with strings attached for ease of retrieval.)

The gun wielding consultant I remember well. I’d been advised to leave socks on, the hospital floor being chilly. Ever noticed how you feel twice as naked when socks are all you have on?

I lie. On each occasion I’d have changed into a cotton gown. But the nurse sitting in without my say so (to forestall, I now realise, accusations of sexual assault) had bid me raise it north of the waist, so the more-is-less rule still applied. The socks and nothing but the socks only serves to heighten, the exception proving the rule, that sense of being naked and eyeballed by a bunch of strangers who aren’t.

And no, I never did get the logic of that oft-parrotted, ‘”they’ve seen it all before”. Yes. And? It isn’t their sensitivities I’m bothered about.

The consultant, of the hail-fellow-well-met school, had a high opinion of his God-given ability to put the patient at ease. Did he think his line of patter an ice-breaker, a sure-fire normaliser of the humiliatingly abnormal? Was he road testing what he’d taken away from that mandatory half-day course on interpersonal skills last summer?

Whatever. The first time he came at my bared and puckered he’d seen fit to precede the dart play with an assessment of my hosiery: black, with mauve heels and toes.

Hmm. Love the socks. Marks & Spencers unless I’m much mistaken.

I’d faked an appreciative tee-hee. Given our respective roles in this comedy of arrows, it seemed the smart thing to do. And FWIW, he wasn’t wrong. The socks were indeed M & S.

Be that as it may – and I’ve had clinicians behave far worse, 5 while the tissue grabs were more disconcerting than painful – it came to pass that, after three such ordeals at twelve firings per session, I found myself once more in that same room. Fully dressed for once, and smiling at the nurse – middle aged and plump, Afro-Caribbean and totally fanciable – I heard him deliver the lab verdict on thirty-six darts up the derriere.

Looking good. But there’s one part of your prostate we can’t get at this way. To be on the safe side we need to fire a few up your john thomas …

Who the fuck in this day and age speaks of a ‘john thomas’?

Not that this was uppermost in my mind. Either because he registered my horror, or because he’d anticipated and savoured it for a few seconds before putting me at ease, he went on to assure me I’d be asleep.

On that basis I signed up for a fourth and frontal biopsy. I didn’t then know about the liberties consultants and their students frequently take – in a teaching hospital – with the anaesthetised patient. To this day the ethics are grey, and notions of what does and what does not constitute informed consent a matter of muted debate. Consider this old hand, urging medical students san frontieres to set their misbegotten scruples firmly to one side:

It’s surprising how worked up people get over this. She will be naked on a brightly lit table for all to see. A medical student will put a tube into her bladder. We’re about to flay her belly open and remove her uterus and ovaries. But to do a pelvic exam! What a violation!

If you get into this habit of being deathly afraid of the patient’s feelings about an internal exam you will never learn how. I’m not saying that you should be a jerk about it, but you owe it to your future patients to get some idea of what stuff feels like.

He’s referring to a procedure with no relevance to a hysterectomy being conducted – carpe diem – by students waiting in line for a spot of pelvic hands on. The above is from a Forbes piece but it’s no different for Brits 6 – and no different for men:

On his last night of a one-week urology rotation, Dominic felt sick to the stomach. “I feel I just sexually assaulted a patient.” He was a third-year at medical school, and had been given a list of tasks to complete. Halfway through a meeting with his clerkship director, it became clear that some students had not yet performed a prostate exam.

She told them, “Come in at 11:15. Then you can check this off.”

When Dominic and a classmate arrived, an elderly man-was under anesthesia, likely for a prostate removal but no one explained or told him the man’s name. Dominic scrubbed his hands, then he and the other student performed prostate exams in turn. He thinks five or six others did the same, on the same man. “I felt really sneaky. I’d violated a patient to check off a requirement for a pass/fail.” 7

I don’t say there’s no defending such practices, even when of no direct benefit to the patient. I do baulk, however, at the cavalier assumption that consent – properly informed consent, not a weaselly catch-all tucked into the small print of a waiver form never meant to be read 8 – need not be secured in advance. Indeed, some sources report all such talk being flatly dismissed on the ground, explicit and unapologetic, that to seek meaningful consent could not but lower the availability of learning opportunities.

Don’t ask; don’t get refused.

Hmm. How about learning how to ask, and crediting the askee with a modicum of maturity, and generosity of spirit? Oh yes, and if there’s still a shortfall, how about students practising on one another – and for that matter on their teachers? Granted, they do need access to pathological conditions – an enlarged prostate, say – but (a) these are a subset and (b) that’s where the arts of non patronising/non coercive communication come in. 9

As we’re about to see, I’ve always been minded to accede to such requests, properly made. On the other hand I’ve always minded, though the degree of my discontent has varied with context, not being asked. 10

*

Needless to say, ninety-five percent of the above was left out of what I told that student nurse. When she exited, what she had on her clipboard was shorthand for (a) the events so far of this November Monday in 2021; (b) the fact of those jabs, two days earlier; (c) the bare essentials of Prostate Scare 2011, and my subsequent clearance; (d) my answers to her scripted questions on such as pee frequency, faecal blood and sexual activity.

She was back in minutes, doctor in tow: a thirty-something of calm disposition and not a hint of that hideous faux joviality in his manner. I’d already had two bladder scans. (I wonder now if the purpose was not only to measure its fullness but to effect an abdominal massage conducive to breaking the waters.) He now did a third, then gave me to understand he wanted to do a DRE.

I’ve made clear I don’t mind a student of either sex being present at intimate examinations. I do attach conditions though. At start of one of my 2011 dates with the dart gun I’d been asked if I’d allow an observer in. Happy to do my bit for clinical education, I’d given my assent.

Minutes later, Doctor Sock had invited his mentee to slide in a tyro finger for a feel of that pesky prostate. This went way beyond the confines of the search warrant I’d granted, but the student had had the decency, the courage even – since it could be read as an implicit questioning of The Man’s authority – to ask if I minded. Feel free, I’d replied, my show of world-weary nonchalance a mask for my dismay at having surrendered all control the moment I assented to a fourth party in the room. Given my position, whether viewed physically or quasi-legally, I’d left it a tad late in the day to be putting up No Entry signs.

Only when about to make my exit and get dressed had I asked her level of study.

I’m in my first year.

I’d done the sums. A few months earlier this slip of a girl had been sitting her A-levels. My elder daughter could give her ten years. Which thought had pissed me off, but what pissed me off a whole lot more was a chance encounter in the corridor ten minutes later. Now fully dressed, I’d given a smile of recognition and acknowledgment.

She’d blushed and, in her mortification, cut me dead. I made a sacred vow there and then. From that day forth I’d allow no trainee observer to intimate procedures unless I deemed their level of study sufficiently advanced. Gaining an early taster of clinical realities wouldn’t cut it.

And if they passed that test? Then I had a follow up. I’d engage them at the outset, making eye contact and asking a question or two. What I asked wouldn’t matter: home town and football team would do. Failure to look me in the eye, return my smile and field my small talk would be an instant fail. I’d politely ask them to leave.

So why – we’re back in November ’21 now – did I not apply these tests when the doctor, having done the bladder scan and now donning the latexed and lubricated, asked me to lower jeans and boxers, roll onto my side and face the wall? Though he’d sought permission for the deed itself – furnishing the perfect window for a “yes but” conditional assent – he hadn’t asked if I objected to the student’s clinically unnecessary presence.

Which was not only a liberty but so at odds with his otherwise impeccable manner as to tell its own story. That mendacious and archaic term, chaperone, masks the true reason male doctors want a witness – almost always a woman 11 – to intimate procedures on patients of either sex.

She’s not there to support and protect the patient, but to fireproof clinic and clinician alike from allegations of malpractice. Which, again, wouldn’t piss me off half as much if they (a) asked, (b) explained and (c) didn’t insult my intelligence with BS about a chaperone.

(As a matter of fact, the doctor did put himself between student and me in a way that blocked her line of sight. While this preserved my modesty it also – being hardly the act of a teacher in practical demonstration mode – served to confirm the realpolitik of her presence.)

I digress. Though I was mildly irked at not being asked, this student had passed other tests. In our earlier Q & A she’d met my eye while asking intimate questions, had been courteous and, though I hadn’t established her level of study (because I hadn’t known at that point what was about to happen) had emanated a maturity a far cry from that shown by Dr Sock’s mentee. 12

Oh, and there’s also the small fact that I’d by this point successfully emitted a second copious pee. My joy, and attendant magnanimity of spirit, knew no bounds.

*

The DRE done I sit upright on the edge of the couch as the doctor, with the student still present, delivers his conclusions. His non committal observations on the feel of my prostate are of little interest to me. I have annual PSA tests and just this summer had an MRI scan which showed the exact size of said item; its enlargement a good sign, according to my Nottingham consultant.

(I’ve lived a decade in the knowledge that, like most men my age, my prostate is enlarged, but this consultant was the first to tell me that: (a) prostate size is neutral with regard to cancer; (b) blood levels of ‘prostate-specific antigen’ are proportionate to prostate size. The MRI having given the precise dimensions of my prostate, my slowly rising PSA levels made sense. I could, said Dr Nottingham, go down the path travelled in 2011. But he didn’t think it warranted and I wasn’t going to argue. Continuing the yearly PSA monitoring was his advice – since a marked rise would need looking into – and I’m cool with that. 13 )

Aspects of Dr Sheffield’s briefing which do get my undivided attention are that:

- He’ll prescribe antibiotics, and the blood in my urine will cease in a day or two. (Spoiler alert: he isn’t wrong.)

- Had I still been a steel city dweller they’d be keeping me in, catheterised, for a multi-day stay. Since I’m not, he’ll be writing to my lace city GP. I’ll be leaving the hospital soon – he wants one last scan, after a pee, to be sure my bladder is emptying – with my own copy of that letter, which will put me on a two week wait. Within a fortnight I should have a urology appointment. He stresses that I should chase up if need be.

- My date with the urologist will feature a cystoscopy. What most concerns him is the source of the bleeding. A cystoscopy, he says, gives a more complete picture of the bladder than any MRI can. Naturally, he sets out what’s entailed in such a way as to minimise the horrors without straying too far into flat out fiction.

Twenty minutes later, mid to late evening by now, I hit the streets for the first of two buses to my car, last seen at nine that morning on a side street off Abbeydale Road. I’d been to the loo to wash as best I could, and to slide into my Primark boxer shorts and jeans. In that order.

*

All credit to my GP and Nottingham City Hospital, I had my cystoscopy date – December 8, 2021 – within a few days.

By which time I’d done a little homework. On the one hand I’d had the first hand accounts of cystoscopy survivors. (Top tactics for top tacticians: when a medic tells you a procedure is not too painful, look ’em in the eye and ask if they’ve had it themselves.) Two were face to face with male pals, of whom one found the procedure “more humiliating than painful”, the other that it was agony from start to end.

Many more were gleaned from this site. Here’s one:

Never again. I needed a cystoscopy because I had some blood in urine. Note: I have a history of panic attacks but was relaxed. The pain was absolutely intense. I cursed and bit on my hand so hard I bruised it. When he said he was removing it I expected relief but that was intense too. About a minute after it was out I got intense nausea, sweat, and passed out. They hit me with smelling salts. five hours later I still feel exhausted and can still taste the smelling salts.

And here’s another:

I was not told of any potential complications. I had flexible cystoscopy, with local anesthesia. I have been on pain medicines now for 28 days, and had 2 emergency room (ER) visits. Doctors don’t know what’s wrong. I have extreme levels of pain. We just know it’s not a hernia, appendicitis, or ruptured bladder. I can’t move 2 steps without pain. I am angry and no idea when the pain will end. Missed lots of work. I did not need the cystoscopy. Never would have had it if I knew the risks. The doctor talked me into it, made it seem like it would be no big deal and just to be sure.

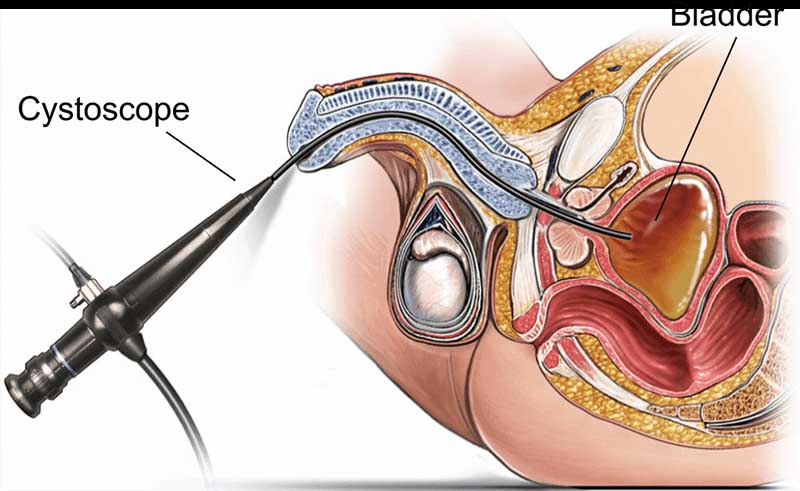

Why does this second respondent precede ‘cystoscopy’ with ‘flexible’? Here again is the image at start of this post:

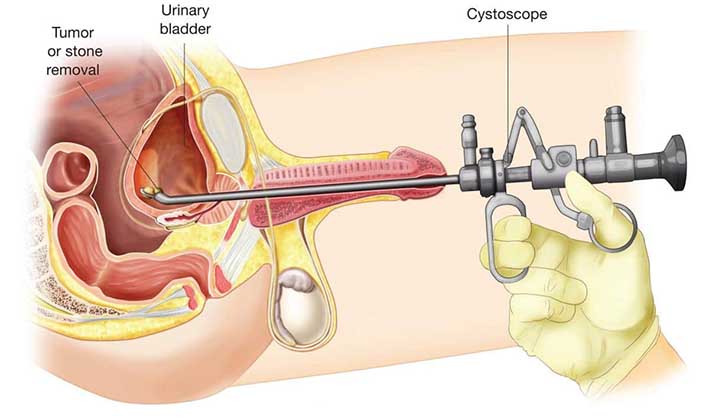

And below is the non flexible variant. (Used, I gather, for intervention rather than investigation, with the patient under general anaesthetic.) I’m showing men. A woman’s urethra is shorter, and there’s no prostate to produce semen. But upstream, things work much the same.

What’s not to like?

Literally on the back of an envelope I drew a 2-D matrix to map all of the survey responses from which the above two are taken. One axis I marked Neutral/Unpleasant. (I saw scant need, in the data or for that matter in common sense, for a Pleasant pole. But do see footnote 3). The other I marked Male/Female, since the sex of a respondent was usually stated.

My rough and ready categorisations – crosses placed in the quadrant I deemed most accurate – showed that men reporting their experience as more or less tolerable were outnumbered three to one by men reporting significant pain. In women this dropped to two to one.

The “man flu” factor? That difference in urethra length?

Nor did the frequency, in both male and female responses, of “never again”, or words to that effect, go unnoted.

(Yes, there’s a bias of self selection to be factored in. The angrily discontented are more likely to speak out than are satisfied customers, gratitude being a famously short-lived emotion. Missing from the list at start of this post, of why we’re poor at stats, and advance suboptimal reasoning, is that in real life the variables soon stack up to make the equations exponentially harder. In the face of uncertainty we tend to reach out to superstition, and aphorisms which don’t always hold up under evidence-based or even logical scrutiny.)

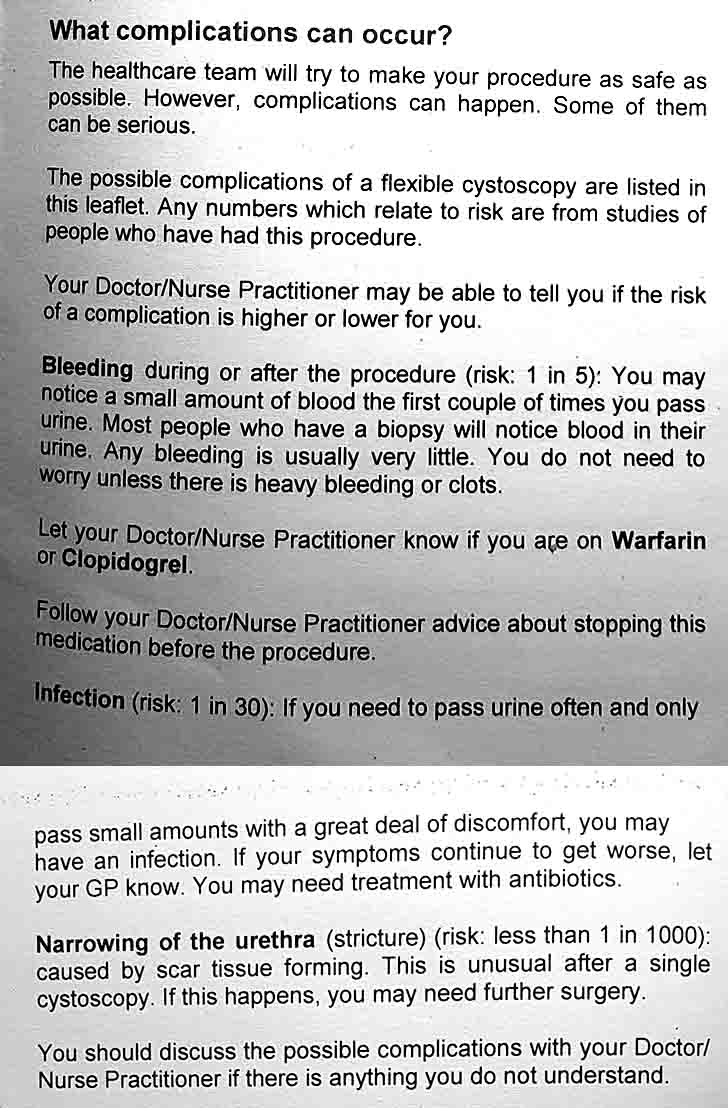

Nor were the reported after-effects any walk in the park. Many spoke to painful urination and worse, in some cases for weeks and even months. Last and far from least, even the literature I’d been given – doubtless pored over by NHS legals – conceded the possibility, with assurances of their rarity, of more serious consequences. Do we really need it spelling out that, if we will go shoving glorified hosepipes up the body’s internal plumbing against the natural flow of things, all bets are off?

*

OK, I get it: for normal people a cystoscopy is no barrel of laughs. But what’s that, when weighed against the benefits of an early detection of bladder cancer?

Glad you asked. Recall that I began all this with a claim that we’re crap at probability. Recall too that no one seeing me had given the coincidence, of haematuria within hours of that double jab, time of day. As I’ve said, and you already knew, it’s a political hot potato.

My online searches didn’t include the c-word. I simply entered “haematuria after vaccination”. Try it. Several papers, all from respected clinicians and publications, are returned. My mind now made up, I saw no need to check, but I’ve little doubt of their peer-reviewed status.

Here’s what I now knew:

- A cystoscopy is likely to be unpleasant and possibly agonising. Once I’d indicated to my GP which way I was leaning, a nurse called Karen rang. Her manner was flawless; the right mix of warmth and seriousness, with ne’er a hint of hard sell. She heard my reasoning as set out here and below, and said general anaesthesia was an option. I won’t repeat all I now know of what may befall the anaesthetised, but the weightier factor for me was that a painless procedure is no guarantor of painless after-effects. Nor that consequences more durable and disabling won’t follow. We aren’t talking painful and undignified but safe, versus pain free but risky. We’re talking balance of risk and, since this is probability assessment, all I said at start of this post applies. Not only is probability not my forte. It isn’t that of your average clinician either.

- What was being proposed was a fishing expedition, just as my experiences ten years earlier had been. This one, however, added real pain to the guaranteed indignities I’d yet again be at the wrong end of. And for what? Nurse Karen told me that nine times out of ten the cystoscope finds nothing. (On the day I attended, another nurse would lengthen those odds to nineteen to one.)

- My gross haematuria began on November 20, hours after my double vaccination. Yet to date no clinician has seen that as worthy of investigation. This despite my having no history of blood in my urine. (I discount temporary haematuria following that fourth and frontal biopsy in 2011. This, I was assured at the time, was an inevitable consequence of those scrapings of my prostate as I lay sleeping.) Given so striking a coincidence, and known links – rare but real – between vaccination and haematuria, I believe the likelihood of such a link applying in my case (a) should be explored and (b) is higher than that of my only sign, in sixty-nine years of existence, of bladder cancer choosing this of all days to manifest itself. In an overstretched and underfunded NHS, (a) lies outside my control but (b) does not.

Nurse Karen, like many others in this saga, did me the courtesy and then some of hearing me out. She then made an eminently sensible suggestion. I had the December 8 slot, she reminded me, so why not attend it? Using the very word I’d later deploy in my banter with Nurse Gloved & Gowned, Nurse K assured me that:

We don’t pounce on anyone. You remain in control of what happens.

On the plus side, she said, I’d get to talk to one of the team about how the procedure works. But her biggest selling point was that in the event (highly unlikely, I thought) of a recurrence before then of Black Monday, I’d still have my place in the queue for that heart-throb, Sister Scopy.

You now know almost as much as I do. I’ll close with a highly condensed version of what befell on December 8:

In a small anteroom I awaited my appointment. As requested, I’d arrived not more than five minutes early but they were running late. An elderly man and his wife sat across from me. After ten minutes they were ushered in and I fell to meditating, once a daily habit and still a far better way of spending idle time than whipping out the phone to check Facebook.

More minutes passed, then the silence was pierced by loud pop music. It began mid song, and ceased two or three minutes later as abruptly as it had started. Recalling what I’d overheard at Sheffield’s Royal Hallamshire, I inferred that music so loud and incongruous could only be to mask cries of pain. Nuff said. When man and wife emerged a few minutes later – cystoscopies don’t take long – I noted his expression. You couldn’t call it serene.

When my turn came, Andy, the nurse who bade me take a seat and tell my story, was courtesy incarnate. He was also the first – and to date the only – clinician featuring in my tale of woe to concede the possibility of the link I’d made, while stressing that the risks lay more in infection from the process than in the contents of either of my vaxes. He added little to what I now knew, other than that – apropos my 2011 exposure to intimate acts when “it wasn’t always clear why everyone in the room had to be there” – two pairs of hands were needed for a cystoscopy.

Cue for Nurse Gowned & Gloved to throw her wickedly playful smile.

Early on I used the word ‘smirking’ in reference to this nurse, but it was lighthearted. I enjoyed our interaction. The team only dropped a point in my estimation of its professionalism (the real kind, not the platitudes of corporate spin) by failing to explain, far less ask if I minded, a fourth person in the room. Since we were discussing matters not everyone wants aired in the presence of strangers, I have little doubt that, had I agreed to the cystoscopy, I wouldn’t have been asked if I minded her staying for Part Two. 14

But nor would I have waited to be asked. Had I heard anything to change my mind that day, and agreed to so invasive a procedure, I’d have taken the initiative and asked her to leave. With her presence unexplained, we wouldn’t have got as far as my tests on level of study and personal attitude. I’d have wanted her gone the moment I’d decided, after all, to unsnap my jeans in an act of highly conditional surrender.

Such a stance may come with a price tag. The survey just cited has one man reporting that after insisting in advance on an all male team, he believed the man in charge (in his case a doctor) was rough, to punish such temerity. We can’t know, of course, but the mere possibility shows how the odds are stacked against patients exercising control.

Then again, consider the battles of the past five decades, led by women even more vulnerable to vindictiveness from a male dominated gynaecology, its writ unaccustomed to challenge. Of course we pick our battles but, if we never fight at all, how will the arrogance and complacency still in play – witness the ghastly presumptuousness of those intrusions under anaesthesia – ever change for the better?

*

As Nurse Andy escorted me to the corridor he advised that, in the event of any recurrence of blood in my urine, I reconsider the cystoscopy option. 15

In that event, I assured him, “I’ll be hammering at your door”.

We may not be born actuaries, but we can all of us revise our risk assessments when the odds take a turn for the worse.

* * *

Notes

- I once foxed a colleague with this teaser: ‘Assuming unloaded dice, which number are you most likely to throw in a Monopoly game?’ His reply was delivered in the sniffy tone of one with a maths Ph.D (why else would I have picked on him?) at so insulting a test. ‘If the dice aren’t loaded, all six sides have equal likelihood of landing face up.’ Ha! What he’d overlooked is that two dice, not one, are rolled in Monopoly. The right answer is seven. Double ha! With brass knobs on.

- You could say the way to falsify a putative link between jabs and haematuria would be to ask whether anyone else, with particular emphasis on those having third covid and flu shots, has reported such a reaction. But a mix of litigatory fear and a super-charged covid debate leaves me doubting I’d get a reliable answer.

- Actually there’s a subgenre of kinky that gets off on catheter play. Nowt so queer as folk, eh?

- Now I can reflect on Black Monday, it dawns on me that what bothered the urology crew at Royal Hallamshire, and what bothered me, were not at all the same. I think they, in their greater wisdom and experience, knew I’d be peeing sooner or later, and were looking further ahead at what unholy conditions the blood might be indicating. By contrast, such abstractions lay beyond my sharply reduced attention span.

- Credit where it’s due. Though I never did warm to his gung-ho style, and won’t easily forgive his trespasses via that first year student, I not only sensed that Dr Sock knew his game. He was also capable, once he dropped the irksome manner, of engaging me in non patronising discussion of what the lab reports might mean. (Biopsies are akin to opinion polls: samples, with all the caveats to generalisation that implies.)

- Actually, it’s worse for Brits. Some US states have in recent years passed laws banning unconsented intimate examinations of no direct benefit to the patient. Britain has not, though some health authorities have had their HR, PR and legal people firm up their policy statements.

- My trawl of sites on the ethics of intimate examinations of sleeping patients returned student reluctance as a major recurring theme, but rarely if ever does demurral lead to defiance. For light on this, see the work of Milgram and Janis – and the many cases in the history books of conscience playing second fiddle to conformity.

- Take my own ‘front-port’ prostate biopsy. Dr Sock had spoken of a simple op, with me going home that night. But at 07:00 on the day, another consultant told me I’d be in for half a week or more. He then reeled off at horse race commentary speed a list of side effects – ‘unlikely but possible’ – taking in such joys as impotence and lifelong incontinence. At that time, sneaky training routines as clinically tangential as they were intimate hadn’t been on my radar. And if they had been? They’d have barely registered, given the competing calls on my capacity for anxiety. In a daze, coffee having been forbidden, I signed on the dotted line. Informed consent? I think not – and of course, I don’t know and never will what took place that day. I know only that three smiling ladies in green counted me down to oblivion, and that when I awoke, with no sense of the passage of time, I was on a ward with catheter running from bladder, by way of John Thomas, to a transparent bag hung from portable gallows for the world – visiting families for instance – to see. Whatever happened between-times is anyone’s guess but I will say this. In 2011 nurses were getting a stack of bad press, led by tabloid tales of poor hygiene and worse manners. For the four days and nights I lay as described, at the mercy of their hands-on intimacies, I was blown away by the professionalism – the real kind, not the inane vacuities of HR-speak – they not once failed to show. One day I’ll post on this. Any professionalism worthy of the name, in the medical or my own teaching context, is about wanting to do the right thing; not fear of being caught doing the wrong thing.

- Yet another option, practised in parts of the USA, is to employ surrogates to let their bodies be used for training purposes. Yes, the objection will be that a cash-starved NHS can barely pay its drugs bills. To which my reply – implicit in the contents of this entire site – need not be spelt out here.

- After each rectal biopsy at Sheffield’s Royal Hallamshire I was asked before leaving to give a urine sample, and sit with it in a crowded waiting room till a nurse eyed it up for blood before letting me go. Sound practice, as I would appreciate ten years later on Black Monday. Less sound was the huge transparent beaker supplied. (The small vial given on my Nottingham visits this year could – once sealed, washed and dried with a paper towel in the loo – be slid into a pocket.) Such indignity was compounded by a waiting area wherein men clutching beakers of wee shared space with accompanying women and kids. When we – and everyone else – heard our name called we were to trot meekly to the nurse’s station with our samples for inspection. Crass, and here too the contrast with Nottingham is unflattering to Sheffield. Urology outpatients at the former have a private waiting area: no friend or relative admitted without good cause. (The elderly man awaiting cystoscopy on December 8 was in a wheelchair, hence the wife’s presence.) After my first biopsy I did as I was told. After the second and third I judged myself capable of spotting blood without a second opinion, and voted with my feet. (I do allow, however, that what is really being compared here may not be Sheffield’s Royal Hallamshire and Nottingham City Hospital, but 2011 and a more enlightened 2021. If anyone has up to date information on this do let me know.)

- In the USA it’s common, I’ve learned, for a doc about to do a DRE or pelvic to call the front desk and summon a receptionist to stand in as ‘chaperone’. What we lay folk need to wise up to is that our awe of a medical priesthood is being hugely leveraged by the arrogance of many – I don’t say all – whose intentions may well be benign, but whose complacency stinks.

- Not her fault at all. Being eighteen is no crime, and ten years on she may now be a glowing credit to her chosen profession. What’s more, her presence that day helped clarify my thinking. You could say I owe her.

- I know two men a few years my senior who, aware they have prostate cancer, have no intention of doing anything about it since, unless it becomes aggressive – quite rare – they’ll die of something else. Thermonuclear war for instance.

- I use the female pronoun because the one person who made no contribution to the cystoscopy room dynamics was a woman in the far corner behind a desk. But with Nurse GownGlove and me the only parties I could identify as indispensable, I can’t rule out the passenger – once the time for words had passed – being Nurse Andy.

- Hours after uploading this post my copy of a letter from Nurse Andy to my GP arrived. It housed this sentence: ‘I discussed … with Mr Roddis and on careful consideration he was not wanting to go ahead with a flexible cystoscopy despite the risk of missing underlying bladder cancer’. As a matter of fact, as agreed with Nurse Andy on the day, I had an ultra-sound bladder scan a few days later. Subject to the lower diagnostic power of this procedure, it gave me the all clear.

Hello Philip,

That sounds like a horrible time; I hope you are feeling better now and aren’t seeing a recurrence of the bleeding/stoppages.

You probably know this, but on the off chance you don’t: the yellowcard scheme (https://yellowcard.mhra.gov.uk/) exists for the reporting of any (suspected) side effects by anyone, including members of the public. They even have specific sections for Corona vaccines. The lack of knowledge of this in the public is pretty shameful, as it seems to be one of the few avenues available to learn about complications/side effects of medication.

Hi Michael and thanks for your concern. Yes, I’m fine. While it doesn’t do to be complacent, I’m happy with my assessment of things, and the decision I took.

No, I didn’t know of the yellow card scheme. I’ll be checking the link you supplied, with a view to reporting my experiences last month. Brownie point deducted from Sheffield medics – and two each from GP surgery and Nottingham cystoscopy team, neither having the excuse of providing emergency care – for not alerting me to this site.

Michael I just made my report on the yellowcard site. Thanks again. I’ll update if there’s any response.

Great piece Phil – a number of big issues and a personal odyssey against the odds to boot. I suspect medical training includes an M&S section in the communication component. I have experienced ‘banter’ about my underpants in a similar situation.

Again, credit where due to Dr Sock. Maybe he hit lucky but, since he was right about their M & S provenance, I assume he, also a customer of theirs, was ad-libbing.

This post could go on expanding. For instance, when Nurse Walk-in was calling Urology at the Hallamshire, I heard her say, “we can’t do that here”. Even in my state of distress I decoded that as a response to an overstretched urology nurse at the other end asking “why can’t you catheterise him?”

Given Nurse No Catheter’s stance, two hours later, that to catheterise a patient passing blood clots is risky, there are likely good reasons for leaving that a call for the urologist to make. Though I’d wanted to be catheterised there and then, I see now that this may have made a deeply unpleasant situation far worse.

If I can find email addresses, I’ll send a link to this post to all who played a role in the drama: GP surgery; walk-in clinic; Royal Hallamshire Urology; Nottingham City Hospital cystoscopy team. No one comes out of this terribly. Far from it. Even Dr Sock would merit a drink on me, in the event we met in the pub one night. And while I’m not so naive as to think my observations and opinions could ever weigh much against the inertia – material, cultural and psychological – of established practice, there’s no harm in throwing them in.

What’s the worst that can befall? Getting a rougher ride than I might otherwise have had, should I at some point opt after all for a tryst with Sister Scopy?

Finally, as a critic myself of the ‘woke’ world of political correctness at large, I should stress that what most matters is that medics are skilled at their job. Forced to choose, any sane person would take the clinically competent but arrogant or inconsiderate over the shining example of respectfulness and interpersonal skills who, truth be told, isn’t fit to practise. But why should we be forced to choose?

Yikes! What an unfortunate experience. I doubt whether I’ll be able to pee again without thinking about you.

I’ve enjoyed good health all my life, Chet, but having turned 69 last year can expect a few body parts to be giving me a spot of trouble. We take our bodies, and a few other things too, so much for granted until something goes wrong …

Having 5 years on you, Phil, is one of the reasons why I can easily sympathize with your situation. About the only advantage – if it is an advantage – to growing older is my noticing that I require less food to satisfy myself.

Well my view may change when I hit 74 but so far I’ve found every age has its compensations. Actually I’d put it stronger. I admittedly had a crap start to my life, so improvement wasn’t that hard. Nevertheless I’m far happier now – despite the needless ugliness all around me given that we’re ruled by the criminally insane, and despite my body not working as well as it once did – than I was as a boy or a young man.

Biggest plus to being 69 rather than 19? Far greater acceptance of oneself.

I thought the nature of the post and the comments were more on the line of physiology, but in terms of life itself, yes, I agree, that aging has compensations in experience, wisdom, maturity, and so forth. Of course, I can still make ridiculous mistakes but not as frequently as when I was younger.

As for world governance, for the most part what I said about aging does not apply to the majority of them. The US (and UK) might as well be governed by a flock of teenagers. Perhaps that would be better.