Years ago I featured as a masthead quote Anatole France’s dry observation that:

The law, in its majestic equality, forbids rich and poor alike to sleep under bridges, to beg in the streets, and to steal their bread.

It’s a truth I’ll return to.

Before the BBC 3 drama series, Killing Eve, descended into farcical self caricature – and to an extent even after that – I and a few million other viewers were mesmerised by Jodie Comer as the psychopathic assassin, Villanelle. It made me want to see her live, in pure farce, when what had impressed me was her amazing facility to switch facial expression – in the blink of an eye, and served perfectly by television’s intimacy of gaze – from the convincingly endearing to the icily insane.

Or even to hold both, and more, in the same instant. I’m no thespian but isn’t that a sine qua non of bedroom farce?

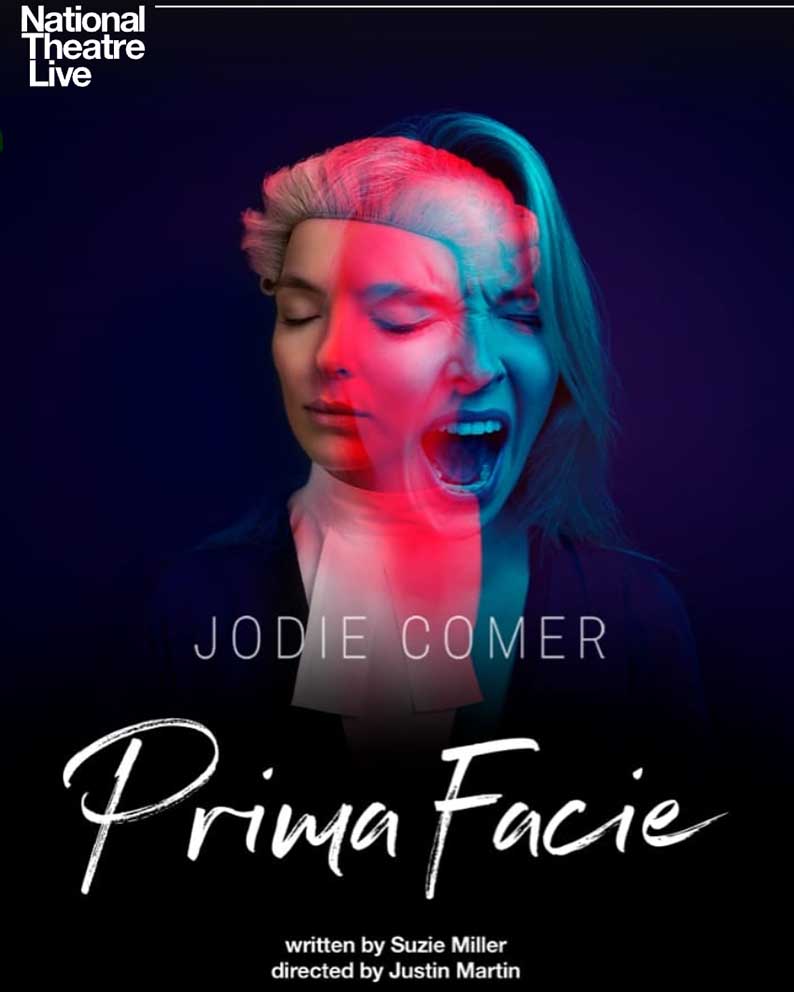

Prima Facie is hardly bedroom farce but does serve up dark inversions of that genre. And while it isn’t exactly live theatre, I did pay twice the going rate for our cinema tickets. That’s because, while we weren’t watching in real time, we were seeing a stage play – penetratingly written by Suzie Miller, directed by Justin Martin and featuring a cast of one in the person of Jodie Comer as barrister and rape victim Tessa – filmed as it was performed at London’s National Theatre.

Ms Comer is incredible.

The plot elements are simple. Of working class scouse origin she is raised by hard work and her own searing intelligence to the status of bedazzling defence barrister. Though in theory working to a ‘taxi-rank’ system – an irony revealed in due course – whereby, like cabbies, barristers may not pick and choose clients, she is by her own account assigned a suspiciously high number of rape cases. Because she’s female and attractive? The question is left hanging.

In many if not most rape cases forensics play the lesser role. At issue is not whether sex took place. At issue is whether the lady said yes. As I put it eight years ago, apropos Mike Tyson’s rape conviction, the prosecution told one story, the defence another, then the jury got to say which story it liked best.

And Jodie Comer’s Tessa is a maestro in the art of sowing, through seemingly sympathetic cross examination of the allegedly raped, sufficient reasonable doubt to get jurors in a long string of courtroom victories liking her stories more than they do the prosecution’s.

But now Tessa is the rape victim; in court, in the witness box – or is it the dock? – and facing an equally formidable QC, public school chum of her barrister rapist, using against her the tactics she knows so well. And not only did sex indisputably take place; some of it was indisputably consensual. With both parties having by their own admission been drunk, Tessa has the uphill task of showing that consensual sex gave way on an alcohol fuelled night more than two years earlier – such is the leisurely pace of the law – to rape.

Whether she succeeds is not the issue. This is no courtroom cliff-hanger.

Two questions are raised: one explicit, the other implicit, but both going unanswered by virtue of being unanswerable. The explicit question, heartrendingly pleaded by Tessa, is whether a man’s truth – or if you like, a man’s story, in a legal system shaped for millennia by men – is the same as a woman’s.

The implicit question is hinted at by the Anatole France quote I began with. It was also explored in my already referenced (and somewhat clumsy) post of eight years ago. Before invoking the Mike Tyson case I wrote:

Low conviction rates, on top of all [that women] endure in court, keep rape hideously under-reported. But … there’s only so far we can go down that path without eroding the right to a fair trial.

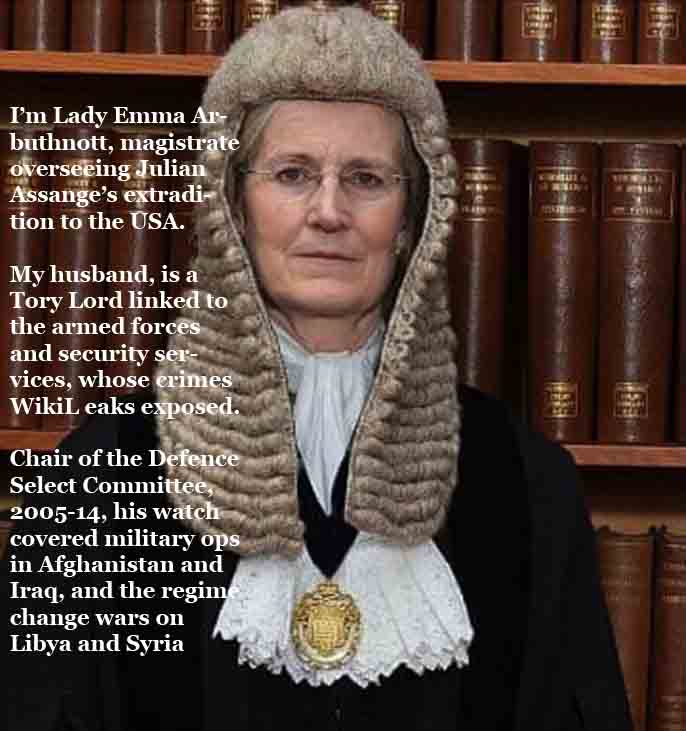

Why? Because as M. France intimates, the law is at best a fine tuned instrument for delivering the individual justice informing our Roman based legal systems. Being shaped and ultimately owned by a ruling class, however, it is incapable – ask Julian Assange, the rape smears dropped once they’d served their purpose – of delivering social justice. That is a truth of general import.

More specifically here, mechanisms for delivering justice for women without jailing innocent men have proved elusive if not impossible. This is one circle that refuses to be squared.

Meantime we have Jodie Comer’s spellbinding Tessa.

* * *