Prisoners the world over tend to mordant wit. Thailand’s most notorious jail is known by its western residents, there to reflect on the wrongheadedness of narcotics trafficking, as the Bangkok Hilton. Closer to home a past Barlinnie Governor, with a Ph.D to his name and given to turning down all and every inmate request, earned himself the soubriquet, Dr No. In the same spirit did ‘classmates’ forbidden from calling themselves prisoners of Chiang Kai Shek’s Reform and Re-education Centre on what was then, due to its volcanic origins, known as Burnt Island whisper their status as guests at Ludao Lodge.

Ludao being the official name of tiny – so tiny that its area is given separate low and high tide quantification – Green Island, twenty miles off Taiwan’s southeast coast and the ideal venue for incarcerating maximum security enemies of the state. Or those designated as such by its ruling caste.

More mordant yet, organised into three ‘batallions’ of four ‘companies’ each, the Ludao Lodge classmates dubbed their dead – by execution, suicide, disease or loss of the will to carry on – Company 13.

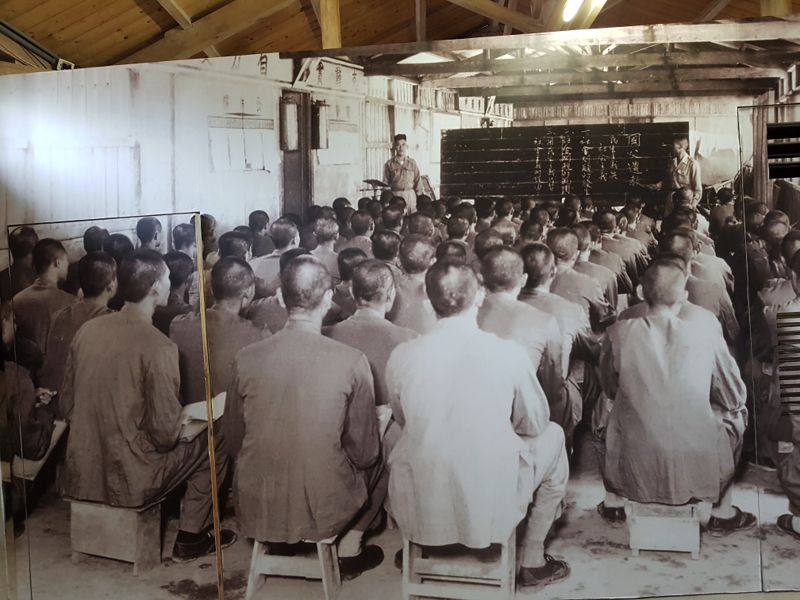

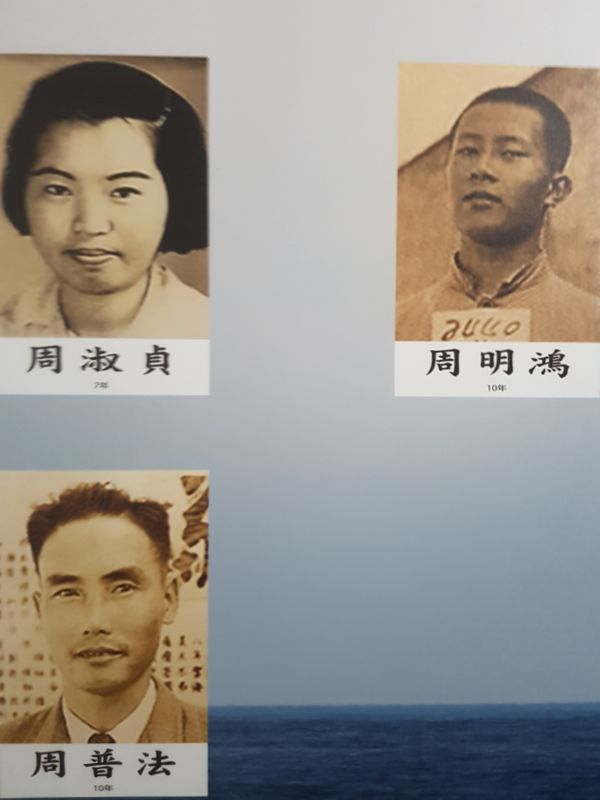

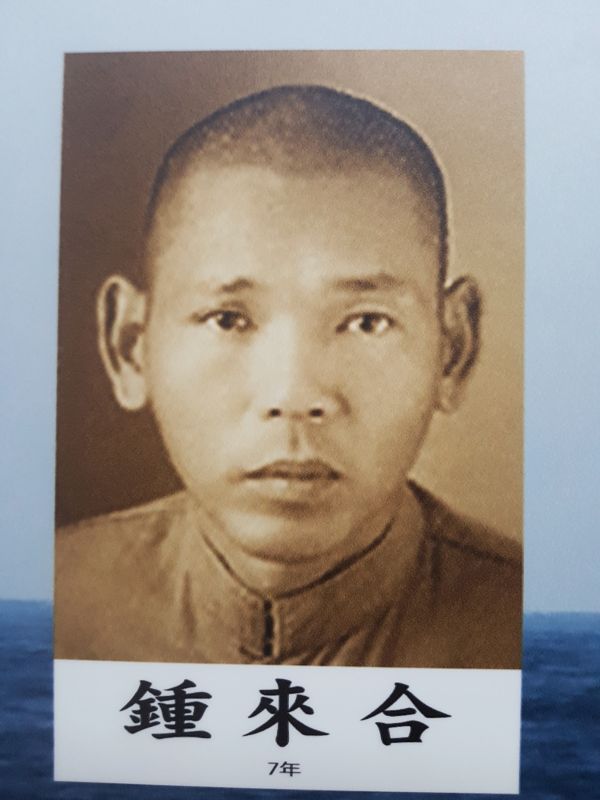

I know such things as general knowledge, and from a visit to Green Island museum, two of its eerily lifelike waxworks featuring in the above images from the Ludao Lodge whose site it now occupies. But let me set the scene. It’ll take a while but the tale is not tedious. That I promise.

*

There’s evidence of Taiwan inhabited as early as 1,000 BC.* These were not Chinese and may be termed aboriginals, as we do those Asians who 25,000 years ago crossed the Bering Sea to populate America. At the same time, Han Chinese were settling on the mainland to the west, in the Yellow River Basin. There was trade between the two but also acts of islander piracy and coastal raids, met with Han punitive expeditions. The Han made no real attempt, however, to conquer peoples – of an island run by warlords – they saw as barbarians.

This state of affairs held till the sixteenth century rise of Europe’s maritime powers. First on the scene were Portuguese pirates, missionaries and merchants – a mix soon to be depressingly standard – who dubbed it Formosa, ‘the beautiful island’, and traded weapons and other tools for jade and marble. A deeper mark was made by Holland, Japan, Spain and, less obtrusively give or take the odd opium war, perfidious Albion. The ups, downs and various machinations of these jockeying powers lie outside my scope but by 1700, China’s Quings took charge, only to cede the island – as their enfeebled dynasty oversaw China’s ‘century of humiliation’ – to Japan in 1895 as part reparation for slights including failure to rein in those buccaneers.

After the crushing of the Boxer Rebellion, an able leader arrived in the form of Sun Yat-sen, at once both China’s Ataturk and its Ghandi. As would the Mahatma’s namesake, Indira Ghandi, Sun admired but rejected Marxism as unsuitable for import. When the Quing Dynasty fell in the early 20th century, he became the first leader of the new republic and is still that rarity, a figure admired on both sides of the Taiwan Strait. But his 1925 death plunged China back into uncertainties set to crystallise around the question, later echoed in the postcolonial struggles of Korea and Indochina, would the new order be capitalist or communist?

I must skip the finer details of that civil war between China’s communists – soon to learn the hard way that Stalin’s approach to revolutionary movements abroad always reflected his narrow political needs at home – and a conservatively nationalist Kuomintang (KMT) led by China’s very own Franco: the generalissimo, Chiang Kai Shek. Instead, I offer this grossly potted version.

Part One, in the thirties the KMT, delighted at Stalin having told the Chinese Communists to merge with it, massacres their brightest and bravest.

Part Two, throughout the decade superior KMT leadership (not the mediocre Chiang but the generals he was adept at playing off) inflicts defeat after defeat on a peasant Red Army led by now forgotten generals working with Moscow advisors. Immediate consequences are Red Army decimation – this is numeric fact not figure of speech – by casualty, desertion and schism. (The fabled Long March to escape KMT encirclement was more than a Dunkirk writ large. It marks a break by the still relatively junior Mao Zedong and Zhou en-Lai with not yet discredited senior cadres, though this too is to oversimplify.)

Part Three takes us into WW2, with Chiang Kai Shek prioritising defeat of the reds over taking on the Japanese invader. Said reds earn kudos by disciplined relations with local populations – though contested accounts say the extent of that discipline, and length of the Long March, are overstated by a cult around Mao – and by firm opposition to the Japanese. Moreover, their forces now battle hardened and more ably led, the communists are at last more than a match for the Kuomintang.

Part Four sees Chiang Kai Shek driven from the mainland onto Formosa/Taiwan. He speaks of this, and maybe believes it since in 1949 the idea would not seem so far fetched, as a tactical retreat, with Taiwan his springboard for conquering China at large.

*

To understand Part Five, which will lead us back to Green Island and Ludao Lodge, we need to factor in the 1945 emergence of the two global superpowers. As hinted in an earlier Taiwan post, the double genocide at Hiroshima and Nagasaki should be seen – there’s ample evidence from the mouths of America’s senior politicians and soldiers – as a demonstration to Moscow of US might.

US opposition to European colonialism – always conditional on realpolitik – soon took a back seat to incipient McCarthyism at home; Domino Theory abroad. Thus it was that Ho Chi Minh, tepidly supported against the Japanese in WW2, was ditched by Washington when Indochina’s prewar colonial administration, discredited by Vichy collaboration with the Japanese, thought to waltz back in and pick up where it had left off. (Not that we should single out France. Britain and Holland had much the same idea regarding Malaya and East Indies – with robust verbal support, in Britain’s case at least, from Truman.)

And so it was that when Chiang Kai Shek foisted his KMT on a Taiwan keen on independence after fifty years under Japan, Washington said nothing. One of the most strikingly consistent features of its foreign policy is an unwavering belief that “my enemy’s enemy is my friend”.

(I’m half way into Andrew Kerr’s Formosa Betrayed. As with other American liberals – Russia expert Stephen Cohen is a case in point – dismayed at ‘wrong turns’ by their leaders, what makes Kerr so credible is his mix of well informed and sincere comment with touching faith in an essentially benign Washington. His title refers to the subordination of Taiwan – “a people who deserved better” – to America’s cold war on the USSR. But the Moscow-Beijing split, and Nixon’s 1972 visit to China, would confer new meaning for the liberal outlook on the idea of Formosa betrayed.**)

Almost there. Justly fearful of China – no longer underrated after Korea, and a 1962 Himalayan border war that left India’s sneering generals humiliated – Chiang imposed decades of martial law now known as the White Terror. Thousands of citizens, Taiwanese and mainlander alike, were executed as suspected communist spies: “better a hundred innocents suffer than a single enemy go free”. Thousands more, death penalties suspended, came to Ludao Lodge on idyllic Green Island.

Tellingly, Chiang’s White Terror mirrored Mao’s cultural revolution, and its narrower but darker echo under the Khmer Rouge, in its disproportionate targeting of intellectuals.

(Should you ever find yourself in Phnom Penh, do visit the former high school known as Tuol Sleng, or S21. Here the Khmer Rouge incarcerated, over the four years of hell ushered in by Kissinger’s illegal bombing and terminated by an exasperated Hanoi, countless thousands of ‘Kampucheans’ betrayed by families and friends fearful of the consequences of not doing so, or by the wearing of spectacles. Each new arrival was processed and documented meticulously, photographed, tortured for information and, usually within days, attached to one of the nightly groups destined for the killing fields at nearby Choeung Ek. When the executioners were told to save on rounds, they used rifle butts and stones. Two things are particularly chilling about S21. One is its banality; eery classrooms with still functional blackboards amid the drab setting of fifties institutional buildings everywhere. The other is the display of thousands of photos: men, women and children, many with expressions of cheerful ignorance of what is about to befall.)

I’ll finish with more images from my visit three days ago to Ludao Lodge.

Final word. Glaringly absent from this account are the views of modern Taiwanese. In my ignorance I’d expected an island universally hostile to Beijing and united in seeing Chiang as father of the nation, albeit a harsh one. For reasons apparent even from this rushed account, the situation is more nuanced, and demographically fragmented. My one in-depth conversation on the matter, with the lovely Sonya of Hualien’s Mini Voyage Hostel, showed this to be the case. (In common with Chinese either on side of the Strait who deal with westerners, she uses an anglicised first name.) Sonya, twenty-two, wants more than the de facto independence her country already enjoys. She wants that status formalised and internationally recognised.

At the very least I’d want to hear from Taiwanese men and women my age or older – a group Sonya acknowledges to be more pro Beijing and pro reunification – but those of that set who also speak English are few and far between. Kerr’s account remains useful but dated. A new assessment is required.

Meanwhile I’ve problems of greater import. Expect my next post to be on hitchhiking in Taiwan.

Hey – explains the book that has just arrived ‘Green Island: a novel’ by Shawna Yang. Recommended to me as a good introduction to the White Terror, told through the journeys of three generations of one Taiwanese family.

I saw that book while searching on Chiang’s White Terror at Amazon Kindle Store. Decided I’d get up to speed faster, given i knew some of the bigger geo-historical context, from Kerr’s dated but detailed account. Look forward to reading the novel though. Fiction has its own unique way of getting at truthd.

interesting things are happening in the rel world.

any nice coconut photos?

See next post.