Does this place look familiar? Right down to the concrete fence post, cracked and crooked?

Then I guess you read my post, earlier this month, King’s Bromley to Sawley by slow boat, one of whose early images was this:

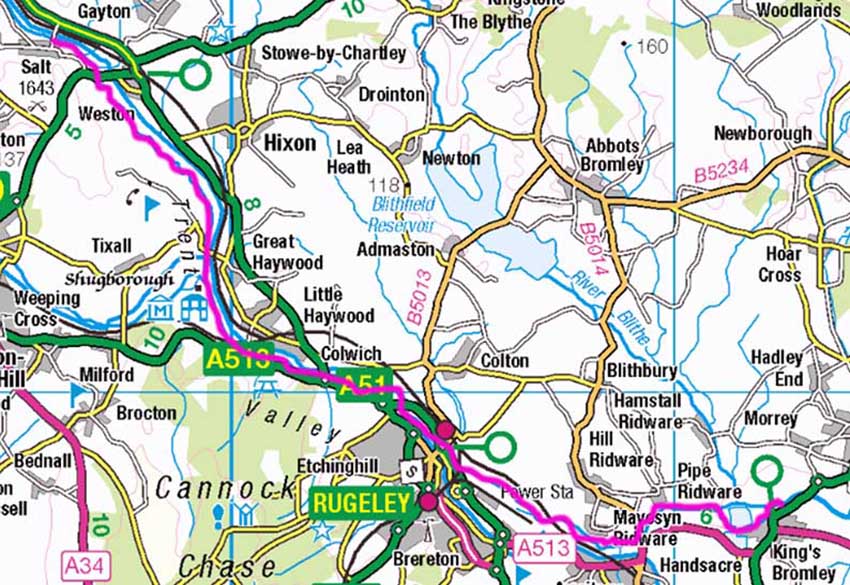

Both show the same stretch of the Trent, from a lay-by on the A515 at King’s Bromley. But image two was taken prior to inflating the boat for a two day trip on September 7-8 to Sawley Marina, thirty-five miles downstream near the Derbyshire/Notts border …

… while image one was taken yesterday, prior to deflating it after a less arduous two day trip taking in the seventeen miles from Salt down to King’s Bromley.

Before I go on, there’s something I need to get off my chest. In King’s Bromley to Sawley by slow boat, as I was describing my first few minutes afloat, I wrote as follows:

With next to no rain for weeks past, the river is low. In the first few hundred yards I have to get out twice …to tow the boat over pebbles and a scant three inches of water …

… I’d mooted a put-in at Weston, a good fifteen miles upstream of King’s B. But with only one and a half days to do this trip – I’d a walk planned with a mate on Thursday – I knew I’d never be home by Wednesday evening or even, at a push, early on Thursday morning.

Just as well. Eventually I want to canoe as much of the Trent as possible. Realistically, that means as high as the downstream outskirts of Stoke, doable after heavy rain. Next spring perhaps, but not now. Not if I had a fortnight to make the trip.

While we at steel city scribblings aim for the highest standards of truthfulness and accuracy, this was complete and utter bollocks.

For that earlier trip I’d put in, recall, from Yoxall Road (north of the church) where its direction changes from north to northeast-bound. But since writing the King’s Bromley to Sawley post, I’ve studied the OS map to see the Trent bifurcating just over a kilometre upstream.

It enters the map near the northwest corner, to divide just before the flooded quarry. The main stream heads north then turns east to skirt the quarry – accessible only to angling and sailing club members, and to wealthy residents of a gated community on the southeast shore close to Manor Farm.

(Accessible too to the intrepid canoeist, but I’m ahead of myself.)

A lesser stream heads southeast to feed the mere at that hour-glass neck between its northern and southern expanses. It exits east of the neck to flow east by northeast toward the Yoxall Road stretch of the A515, where I’d put-in on September 7 and where I will finish this trip.

How do I know this southern stream to be the lesser? By revisiting King’s Bromley last Sunday. A pleasant ramble, west of the flooded quarry – its tree lined waters hidden from public view – crossed a footbridge over the Trent a hundred metres upstream of the fork. Two hours later, as I pointed the Skoda at Lichfield for a spot of rubber neckery followed by pie and pint, I did so in the knowledge that in postponing a put-in …

… at Weston, a good fifteen miles upstream of King’s B [pending] heavy rain …

… I’d been unduly pessimistic. There was every likelihood of a goodly flow, even in current dry conditions, from Weston if not further upstream. What I’d thought of as the main river, reduced by drought to a thin trickle, was in reality its B-team effort.

*

The next day sees the woofers and me motoring up to Weston Bridge, where the Trent passes under the A518. Turning off that busy road at a track to a padlocked gate two hundred metres away, I park up and walk back. Either side of the road the bridge towers over river and both banks. No chance. I also rule out getting self and kit over padlocked gate to cross the meadow to the water. Schlepping over that expanse of cow munched grass – canoe trolley useless on rough ground – I’d be about as inconspicuous as Raymond Chandler’s tarantula on angel food.

I’d need twenty-five minutes, minimum, from traversing gate to getting afloat. The meadow is not only devoid of cover but overlooked by Weston Hall Hotel, a listed Elizabethan mansion. I don’t mind a spot of flash trespass but experience tells me the rural bourgeoisie trade funny handshakes at the same masonic lodges. A phone call from hotel to nearby farm would soon have Land Rover Man – all Barbour, flat cap and green wellies – showing up to ruin my day.

And me with no Plan B.

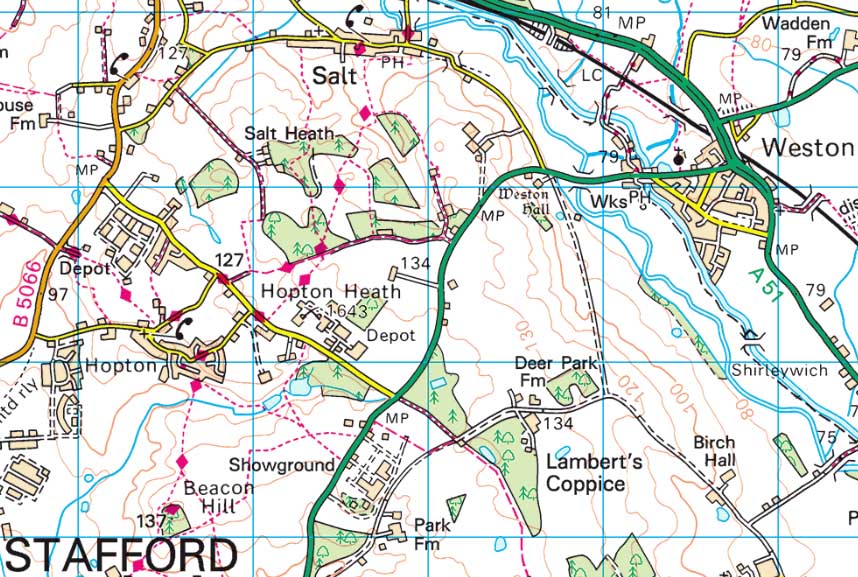

What’s this though? The OS 1:25000 on my phone shows a bridge a mile upstream, at the tiny village of Salt. Why don’t I turn off the A518 to take this country lane and give it the once over?

*

Two days later, and two days ago, sees me at the bridge in question, on the bank of a smaller but clearly canoeable stretch of upper Trent..

I already knew four hours and four buses would get me to within half a mile of Weston Bridge. I figured I could go the extra mile, even with kit, to Salt. Then Google Maps delivered gold. It told me that, after Weston, the 841 Uttoxeter to Stafford called in at Salt – two hundred metres from the spot I’d identified, after giving up on Weston Bridge, as an easy put in.

09:36 Beeston-Long Eaton … 09:53 Long Eaton-Derby … 11:00 Derby-Uttoxeter … 13:12 Uttoxeter-Stafford (calling at Old School Lane on the edge of Weston, then Salt)

At 13:45 I’m off the bus and a minute later crossing the Trent. Inflate by roadside, heave boat and kit over gate by bridge, and I’m at my entry point. Camera metadata shows the above was taken at 14:06 on Wednesday, September 22. Seconds later I’m afloat.

I’ve spent too many words getting to this point. I’ll use fewer now.

*

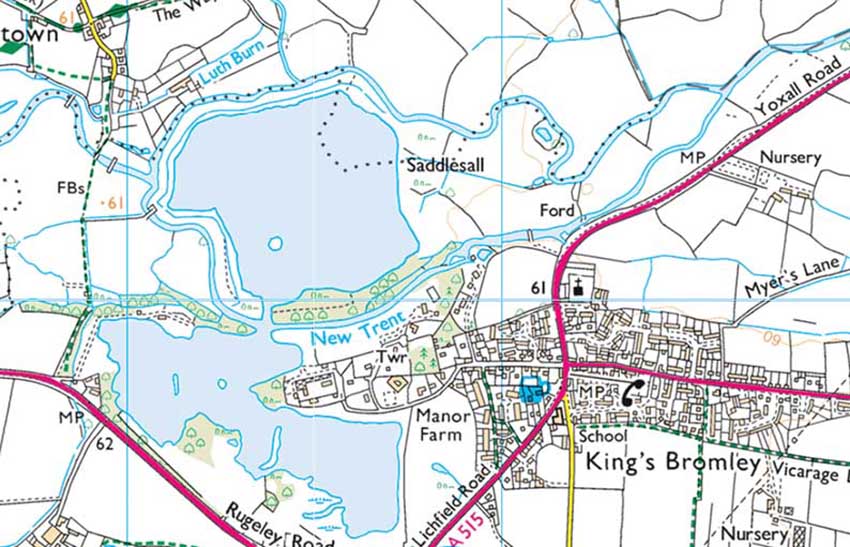

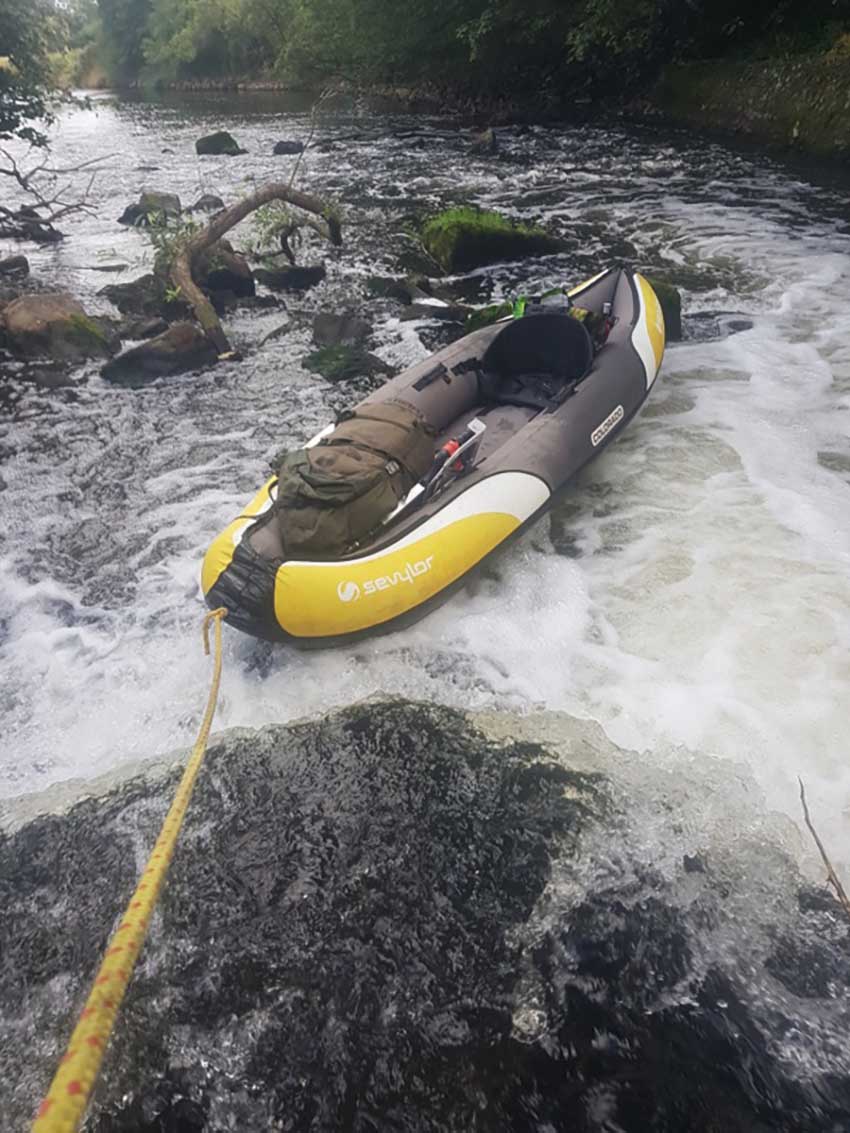

Weirs? You know my methods. Pace Clint, in his empire-serving Heartbreak Ridge, I improvise and overcome. Again I have two to negotiate: this one at Hoo Mill, late afternoon on day one, with canoe trapped at the lip by a tree trunk and me up to my arse in river …

… and this one on day two, a few hundred yards from journey’s end, where that lesser stream after the bifurcation has left the flooded quarry at King’s Bromley:

My technique may vary as I adapt to the particulars of each. But both are tackled, respectively, in the no nonsense manner you’ve come to expect.

Other challenges? At eight am on day two, at the King’s Bromley fork, I take the minor stream to pass through the flooded quarry to journey’s end. (Taking the major stream would oblige me to paddle back up the minor’s swift current, from their point of reunion, to lay-by and get-out.)

I find myself on a gloomy creek crowded out by willows that evoke my nightmare experiences of July 2019 on the River of Fear.

While the occasional fast run gives relief from the creepy stillness, it also ups my anxiety. As on the river of fear – some call it the Leicestershire Soar – no egress is possible via the banks. Both are steep and muddy, leading to a vastness of dense scrub and nettles. Should I hit an impasse, coming back upstream will be my sole option.

And it will be made all the more daunting by these otherwise welcome fast stretches.

But I encounter no impasse; just a few scares. After half an hour of threading through tiny gaps of opportunity between fallen willows and the debris they trap, I paddle joyously into the open water of that flooded and inexplicably nameless quarry. Within the first minute, as I head out for my island in the sun to make coffee, I spy great crested grebes – a sure sign I’m on deep water.

Sleeping arrangments? When I began wild camping by canoe – here’s an account of my first trip in 2018 – I took the same lightweight tent I’d used for several years on walking trips. It did me well on Windermere but a second jolly the same summer, on the Border Wye, showed the drawbacks on a fast river. In another post of the same trip, I wrote:

When wild camping, all the usual criteria apply. Bogs and dank woodlands are a no no, ditto the haunts of knaves, varlets and teddy boys. But now there’s the added requirement of seclusion, what you’re doing being not entirely kosher. To this we can add that the ideal site must present itself at the right time, a two hour window before dark descends. All too often I’ll find a perfect pitch, but too early in the day.

Wild camping by canoe makes additional demands. Is the pitch close enough to the water? Can you even land? The border Wye has long stretches of high vertical bank or dense brush, else mile on mile of Private-No-Landing signs – not that they’ll stop me, come nightfall – to further constrain choice. There may also be added challenge from currents fast enough to demand the spot be assessed in seconds, between first sighting and sweeping downstream of it …

Bear in mind that each inspection requires getting out – not always easy – and beaching with due care, to remove all possibility of watching helpless from the shore as kayak sails downstream with all your kit and no one at the helm.

By moving from small tent to bivvy bag, the overnighting opportunities rise exponentially. On dry nights I can sleep on meadow or shingle beach, cushioned from any hardness by the air chambered floor of the canoe which, seat and kit removed, is my bed. Rain forecast? I haul up under a bridge or, if I can’t reach the next one before nightfall (canoeing a fast river after dark being my definition of a death wish) tough it out in the waterproof bivvy bag.

That’s what it’s for. Though with rain in the offing, sleeping in the boat is not without risks. Best upturn the boat, kit stowed beneath, and let hard earth be my mattress. Either that or invest in a tarp to turn canoe into tent. More to carry though.

With the light fading on day one, I wash up on a shingle beach for the easiest of get-outs. Above the river a sheep grazed meadow is bordered on the far side by a railway line. It all looks good, especially when I see that halfway up from shingle to meadow proper a grassy shelf juts out. It’s long and wide enough to provide a platform bed, out of sight of passing trains.

Here’s the view as, teeth brushed and flossed, I’m about to rest my weary head.

The trains passing every few minutes, mainly goods, don’t bother me. As I gaze up from my cot at the stars, lighting up one by one in a cloud patched sky, their whooshing rush and bass rattle periodically mute then duet with the melodic hiss of fast water on pebbles.

The view from my bed in the morning. Usually I’m up at first light but, although the night was cold, I’m well wrapped and in no rush. I’m barely five miles from King’s Bromley and, with no livestock in the meadow, unlikely to be disturbed by Farmer Giles on dawn patrol.

But what is point, canoe camping? Glad you asked. For one thing, for me as for many others, there’s the buzz of overcoming the many problems. These may be relatively major, as with the weir at Burton described in King’s B to Sawley. Or, so far worst of all, on the river of fear.

Or they can be minor. After the weir at Hoo Mill, my shorts are soaked. Given the curtailed and cooler days of late September, by the time I haul up on that shingle beach my bum’s a block of ice. Off with sodden shorts and wickable undies, on with the fetching merino long johns I sleep in on cold nights. But these won’t do next day. Not even in their newly purchased prime, far less now the moths have devoured an inch diameter hole over left buttock.

But this much I know. One, the night is forecast as dry, cold and windy. Two, in the middle of the meadow stands a lone oak. Three, if I can reach low lying middling twigs – not too thin to bear the weight but not so thick as to lack elasticity – I can pull my shorts over them and know they’ll stay put.

In the morning I’m donning wind-dried shorts. If you don’t like this kind of problem, and the joy of finding solutions, then, no; camping, least of all on the wild side, is not for you.

(Though I make a mental note to never again take the canoe out, not even on a day trip, without a full set of spare clothes in a dry sack.)

Even the painstaking planning of bus after bus – taking half a day where the drive would take fifty minutes – is fun. That’s why I torture you with the details. Not only do I ride for free at my time of life (as would we all if not ruled by criminals for whom profits trump environment every time). Renewed is the soul whose owner negotiates the swirling currents with nothing – least of all a motor – to puncture the nomadic ambience with its whining, come-back-for-me!

Only the song of the paddle. And call of the wild. On day one I notched up a personal record of eight kingfishers!

No. This wasn’t taken on the Salt to King’s B jolly, none of whose eleven kingfisher sightings – 8 + 3 – showed a static bird. I took this in February 2016, with the kind of kit I don’t mind taking on the canoe – see my Norfolk Broads shots – but not on fast water or when bivvy camping. I’ve yet to spy a static kingfisher while afloat. Typically my near silent approach disturbs them at the last second, to send them speeding low across the water ahead in a thrill of electric blue.

Tell you what though. With the kit I now have – I moved this year from SLR to mirrorless, and have better lenses as well as more experience of bird photography – I’d get much better shots given the opportunities laid on a plate for me sixty-seven months ago when a nesting pair took up residence at a pond in a park three minutes walk from Steel City House …

Finally, some of the scenery as captured on my phonecam, encased in a plastic wallet, water-proof but transparent, on a cord round my neck. The Galaxy S7 supports instant, one-handed snappery even on a locked phone.

* * *