Miko will be fifteen tomorrow though he doesn’t look it. “Ask my mother!” he cries indignantly when I voice my doubt. I might at that, but first I need to get off the street and put some food inside me. I haven’t eaten a proper meal since getting mild sunstroke in the hills above Udaipur a week ago. It laid me low one day only – which is getting off lightly, not that I deserve it: I’m old enough to know better – but my appetite is only just recovering. That’s where Miko comes in. Wandering near the bazaar on Sunday night, just as everyone’s shutting up shop and the lights going out, I’m resigned to grabbing puris and dahl from a roadside handcart when this lad of twelve, as it seems to me, materialises from a doorway to establish that I am indeed looking for nourishment, then lead me up three narrow flights of stairs to what he claims to be the best food in Bundi. Thus did I encounter Energy Cafe.

And yes, the food – I chose mattar paneer with roti – is good, and ridiculously cheap even by Indian standards. Though I don’t want one now I notice the place is one of the few round these parts to serve beer. The hippie decor and huge mural of Bob Marley explain that; ditto the fact the place not only advertises espresso – scores of joints do the same without being able to deliver – but, when I press the matter and ask to see it, proves to have a proper Italian coffee machine. So as I pay up – not failing to run an age check on Miko past his mother – I assure her I’ll be her first customer in the morning.

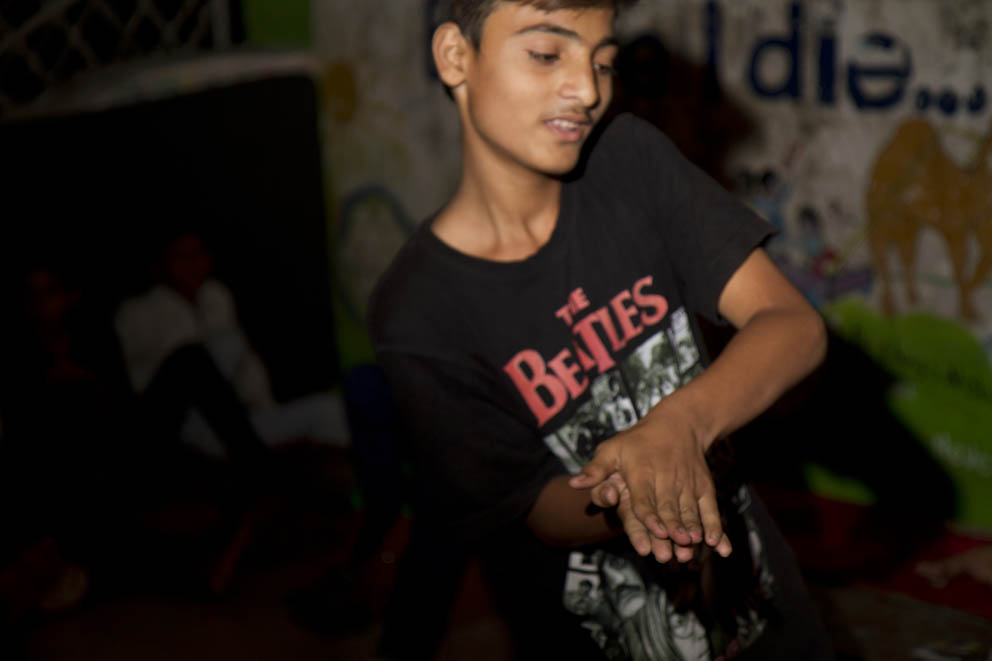

As indeed I am. It’s seven thirty on Monday, with Miko and younger sister Gun-Gun about to set off for school, when I arrive for my coffee. I tell Miko he now looks fifteen, and am rewarded by an invite to his birthday party that evening in the Energy Cafe. “There’ll be dancing”, he assures me, then leaves with his sister.

Over coffee I watch parrots fly to perch on the rope artwork overlooking the street. Like most cafes this is an open air balcony, shaded from above by Indian cottons held by bamboo frames. I take my pictures then sit back with my coffee. By now I know Mooni, Miko’s mum, and Pappu his father. I also know Pappu’s business partner Raja; both of whom hail from Pushkar, further north. They are running two budget hotels as well as this cafe, having tried to make a go of selling Indian clothing to tourists but finding, as the latter have grown more skilled at barter, margins cut to the bone. Having seen my camera kit, Raja wants me to take pictures of one of the hotels, a traditional town haveli a stone’s throw away. Waiting only for a refreshing mint with lemon cooler – which is not only gratifyingly thirst quenching but takes a mere hour to prepare since the market, from which ingredients must be freshly procured, is close by – I go off with Raja to take his pictures.

It’s love at first sight with the haveli hotel. The place oozes character. I want to stay here. The shots in the bag, Raju takes me back downstairs and introduces me to Kamla, a matriarch who could give me ten years. She’s being visited by the milkman, a pleasant old codger in Rajput get out who stops for chai. As do I. Over which Kamla produces a laminated cutting of a full page feature in Britain’s freebie paper, the Metro, featuring her and two adult daughters. The gist is that in this land of patriarchy, Kamla and daughters found themselves respectively widowed and yet to be married, with no obvious way of making a living. Savings were invested in the haveli, a thriving business built up, but the daughters have since married and moved on, leaving Kamla in need of a manager. As far as I can tell that’s where Pappu and Raja come in, though the arrangement looks closer to mutual entrepreneurship than employer/employee. My guess is they pay Kamla an agreed rate, then pocket any excess.

Today I moved in to the “Maharajah Room”. Last night I went to Miko’s party.