Don’t say ‘earwash’. I’ve penned this ode to not making a fool of yourself around these parts.

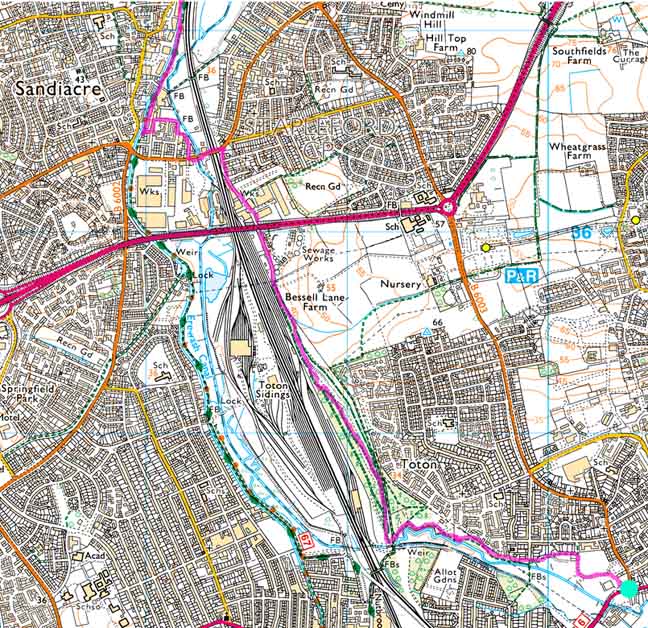

Yesterday I drove to Toton Fields, bottom right on the map and a mile east of Long Eaton, to let the dogs out. It was nine-twenty, the sun strong but with a stiff northeastly. Soon we’d be glad of the latter but now it had me shivering in shorts, t-shirt and sleeveless top.

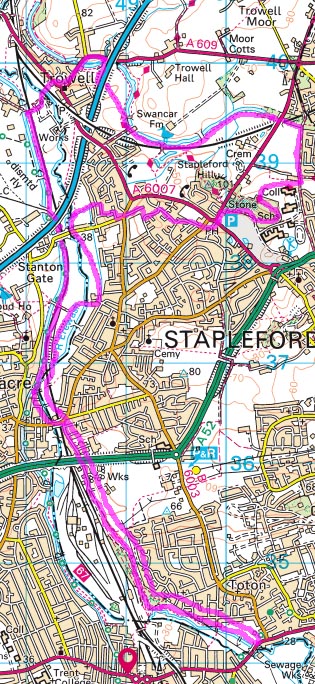

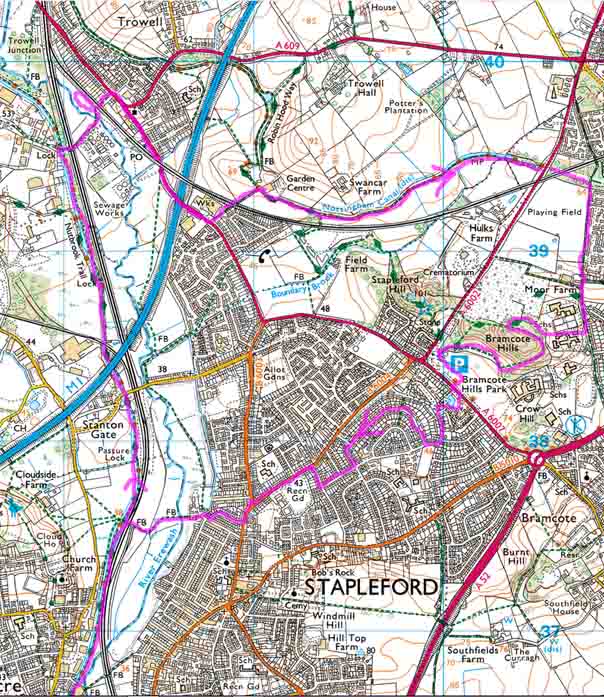

[ezcol_1half] [/ezcol_1half] [ezcol_1half_end]I’d no plan to walk as far as we did, though I had food and water for us all. In the event it would be just before five when we got back to the car. With a sedate pace and a few stops – twenty minutes for lunch, fifteen for mid afternoon feet up, many snap stops and many more to study the OS 1:25,000 on my phone – I don’t suppose we averaged above two miles an hour. Even so, that would make our walk a fourteen miler, though feeling longer given time spent adrift on the crescents and cul-de-sacs of deepest Stapleford. With grid lines a kilometer apart, that more or less tallies with the (clockwise) route taken.

[/ezcol_1half] [ezcol_1half_end]I’d no plan to walk as far as we did, though I had food and water for us all. In the event it would be just before five when we got back to the car. With a sedate pace and a few stops – twenty minutes for lunch, fifteen for mid afternoon feet up, many snap stops and many more to study the OS 1:25,000 on my phone – I don’t suppose we averaged above two miles an hour. Even so, that would make our walk a fourteen miler, though feeling longer given time spent adrift on the crescents and cul-de-sacs of deepest Stapleford. With grid lines a kilometer apart, that more or less tallies with the (clockwise) route taken.

The approximate meaning of Erewash is not in doubt, but there is room for debate about the precise derivation and its connotations. Brewer gives the commonly accepted explanation that it comes from the Old English words irre (‘wandering’) and wisce (‘wet meadow’). This is accepted by Cameron, a leading placename expert and Derbyshire specialist, who interprets the name as “wandering, marshy river”.

wiki[/ezcol_1half_end]

Like the Soar – see Soar on Sunday and River of Fear – the Erewash fascinates me, and for the same reasons. In some respects they mirror one another. Both join the Trent, their confluences not far apart, though on opposite banks. The Soar flows north through Leicestershire to come in at Ratcliffe Power Station, across from and barely downstream of Trentlock. The Erewash, much of its course the Nottinghamshire border, flows south through Derbyshire. Prior to the onset of quarrying in the nineteenth century, it met the Trent two miles downstream of the Soar’s entry.

The Erewash looking down to the old lace mill, now apartments, on Gas Street at Sandiacre

Both rivers offer rural idyll and industrial heritage; both teem once again with chub and barbel. Both too are on my kayaker bucket list. River of Fear experiences notwithstanding, I’ve a mind to canoe from Trentlock, where Erewash Canal meets the Trent across from the Soar’s entry …

(If you can improve on the above let me know, but no smut please. This is a family site.)

… the idea is to take the canal due north. It runs roughly parallel to the River Erewash, mostly to the west but crossing it at Eastwood, of DH Lawrence fame. There I’ll take the river down past Ilkeston and Trowell, Sandiacre and Long Eaton, into Attenborough’s flooded gravel pits.

Until the nineteenth century that final stretch would have been a marshy delta. Today the Trent has flood plains where rugger is played by folk who change and shower in dressing rooms on stilts. For its part the Erewash ends up losing identity and upstream purpose to the man-made meres of Attenborough, their sluiced outflows assuming control of all exits to the Trent.

If all goes well that’ll be a four day trip, I guess. That’s a big if though, and one that brings me to another similarity with the Soar. On foot we only get occasional glimpses of the Erewash, most often from bridges. Flowing through railway land and horse pasture, past factories abandoned or working, access points are few and far between. My sense from these glimpses, and those stretches where you can walk the banks on open meadow, is of there being less of the felled willow and choked current that brought me such sorrow on the Soar. But a sense is all. On gems of impressionism do the dreams of pioneers blossom and flourish, then wither and perish.

The sole chokepoint I spied for the Erewash kayaker. On the Soar their name was Legion.

But sufficient unto the day the ramblings thereof. Today I was an ordinary man, flesh and blood like you, out walking the woofers on an April Day that felt more like May. We followed the river through Toton Fields, then left it to pass ponds where tadpoles swam, the ground rising to the birch uplands of industries gone. From hills of impoverished soil we gazed down over concrete and barbed wire, on the ghosts of Railways Past.

I did anyway. The dogs had other interests.

My eyes took in the cracked hulks of locomotives and rolling stock long ago shunted into this graveyard for the rusting by cloth capped men in oil streaked blue. Their spirits surely haunt these sidings of spent destiny but who remembers? Who – other than the sad anorak with his sexless passions, his pencil and notebooks stuffed with numbers – cares?

I remember. I care. And I’ll be back. Soon, with a real camera.

Emerging from an industrial estate on the southeast edge of Sandiacre, we headed west on the town’s deserted high street, crossing railtrack and a culverted Erewash. It felt like an episode of Dr Who. A hundred yards on, we tilted right and north on streets of terrace quietly red, watched over by a towering chimney which long ago quit smoking. I was after a footbridge over the river, now to our right – that OS phone map having assured me one existed. But it too had gone in for the barbed wire and sternly padlocked, sure signs that one’s presence is not required.

I did, however, squeeze hand and phone through the diamond mesh to snap another bridge just upstream.

Describing a square bracket on those eerie streets, I threaded round to Bridge II, only to find it crossable but leading, after a ribbon of meadow on the far bank, into a housing estate whose sole point of egress the map showed up as counterproductive and profoundly suboptimal.

I know when I’m licked. A sign said I was on Gas Street, blocked at the far end from Bridge II by Springfields Mill, now all post industrial chic for the Derby commuter. I could weave around it, I figured, to pick up the canal behind. The clock said we’d been walking eighty-five minutes.

Erewash Canal at Sandiacre

The route so far:

Two hours on the towpath, lunch at a lock included, got us to handsome Trowell, a village a far cry from the M1 Service Station it gave name to. A few pictures along the way …

Another glimpse of the Erewash, east of Stoney Clouds (an oxymoron surely) where it comes close to the canal

A shouted conversation between trucker and biker.

I’d watched in amusement as truck tried thrice to cross, only to be forced into reverse by traffic the other way. Finally, driver flags down biker. I gather from context and snatched dialogue that (a) roadworks have necessitated a single lane contraflow, (b) lights alternating said contraflow are malfunctioning and (c) lorryman hasn’t “got all fucking day”.

At this lock, its name a reminder of my ongoing struggle against academic casualisation …

… we leave the canal and cross the Erewash. It’ll be three hours or more before we’re back on the towpath and heading south. We’re almost as far north as we’ll be going, save a short stroll up the right bank of the Erewash before retracing our steps to cross meadow and railtrack on a northeast vector into Trowell.

Unlike another chap we’ll hear of by and by, this dude keeps his two metre distance as we swap pleasantries on the far side. He’s bound for the disused Nottingham Canal. As – though I don’t yet know it – are we.

Time was, I’d be good for another twenty miles before sundown. Now I’m a shadow of the man I used to be.

On a grass verge in Trowell, studded with daisies, we rest. A cup of tea would be great but no chance of that in a lockdown. Water will have to do.

Tebay’s recall is getting better but I need him on the lead this close to a busy road.

Soon we’re in woodland on ground rising. To our right, the valley east of the Erewash.

We skirt fields ploughed, the good seed scattered on the land.

The Nottingham Canal is now mainly a dry ditch with occasional accumulations of water. We’re a long way east of the river, adding miles to our walk, but these are rambling conditions to die for. Though it’s only April, this sun would be oppressive but for that northeasterly.

The wooded hills of Bramcote.

We drop into Stapleford for forty minutes of negotiating school playing fields, copses, a pond and acres of housing estate. All require frequent consultations of the OS 1:25000 – how I made do without it in the olden days is a mystery – which, along with all the snapping, is drinking up phone juice. For a few hours out, I hadn’t thought to bring power pack or solar charger.

On a Stapleford zigzag dictated by road layout, and wrong turns where I’d thought I knew better than the map, I pass through a street where the kids have gone one better than that rainbow in the window. On house after house, they’ve coloured in the lower brickwork.

Battery death imminent, I pick my way across a recreation ground to enter a meadow. The dogs lap at a brook – they prefer it to my chlorinated tap water – before we cross the railway line yet again, this time on one of the Bridges of Madison County.

My penultimate picture. I know the canal is less than a quarter mile away, in as straight a line as terrain allows – and in any case due west, the afternoon sun as faithful a guide as ever led hiker homeward – so the imminent death of my phone doesn’t bother me on the cartographic front. I can figure a route once I’m on the towpath and heading south.

What does bother me, halfway along, is the appearance at the far end of a young man on a bike. I call to him that I’ll get a move on but he’s not going to wait. Of necessity, as our paths cross, he’s less than a metre away.

“I don’t believe in that distancing crap.”

I too have my doubts, though I’m less scathing than him of flattening the curve. But he’s young and fit. I’m in my sixties. More important than either, it seems the height of uncouth to inflict on others the fruits of our grasp of epidemiology, encyclopaedic though it may be.

“It’s not just about you though, is it?”

I can’t swear I didn’t call his act arrogant. I know he told me to fuck off, and not just the once. But one of many advantages of age is it gets easier to let go of dark thoughts. With a little effort, aided by skills picked up in meditation, I watch the ripples fall away. This is no day for dwelling on the trashily inconsequential.

We pick up the canal half a mile north of Sandiacre, then pass the mill where we’d first joined it, hours earlier. On the northern outskirts of Long Eaton we swing east and left, down genels and back alleys, over the railway line for the last time, into the open meadows and birch woodlands of the Erewash flood plain.

Final snap before the phone dies. We’re a mile and a half from the car.

At just before five pm, Jasper, who dislikes being in the car, leaps onto the back seat as I unzip the Skoda. By the time I have Tebay strapped in, he’s asleep. Would’ve made a nice picture.

* * *

It seems a life time ago now, and I suppose it almost is. But I was minded that I used to travel the Erewash line, in my younger days on the footplate. Usually firing a Black 5 with a good boil on.

Mostly the train would consist of 30 or so coal wagons. The old drivers would refer to the Erewash line as “the clog and knocker.” As we went up the gradients, the engine would get some clog and we would snatch each coupling one at a time. As we descended the gradients, we would rub the brakes and collect up all the weight of the loose coupled wagons. By knocking together the buffers between the wagons. Ready to snatch them again on the next incline. Some drivers claimed that they could count each wagon this way. The guard sat in the brake van at the back, could and usually would get a rough ride.

Many years later I followed the Erewash line again, but this time on my narrow boat. At a much more leisurely pace and comfort. And a lot less of the rough ride as experienced over the clog and knocker.

Regards

Mick

Fascinating, Mick. You are a man of many pasts, I know, but this aspect is new to me. Should you and boat be passing Long Eaton or Trentlock way in the near future, give us a shout, mate.

I left the employ of British Railways, after a couple of years. Mainly because after working a train down from Tinsley marshalling yard in Sheffield to Derby. We returned with a fully fitted Diesel train. With the guard travelling in the other end of the engine. We were knocking it on a bit approaching Ambergate junction when the engine whistle started popping. It was the guard tooting from the back cab. I looked back from my window, to see wagons cartwheeling through the air. I told my mate Ray that we had come derailed. There was sparks, smoke, and fire mixed with the screech of tearing metal, We came to a shuddering halt, with just three wagons still attached to the engine. The rest were scattered all over Ambergate junction. I ran to a signal post and phoned the Derby signal box that controlled all that area. To report all lines blocked. Then set off in the running direction to get some detonators down on the running lines. Bit of a brown trousers moment that was. We all had to go to a board of trade enquiry.

A few months later, we had ‘one under’ when a ganger in a high visibility vest, walked out from the side of a bridge, straight in front of the engine. Slapped everything on, but we could not stop in time. We were stood on a railway embankment. The driver went back to check and I phoned the controller. Half-an-hour later a grizzled old BTP sergeant turned up with a new recruit. They went back for a look, the new recruit fainted and fell down the embankment. The sergeant was totally unimpressed when the new recruit climbed back up and was throwing up. Gave him a good bollocking for being a wuss and asked us if we had any tea. That was enough for me, time to get myself some safer employment, I joined the Marconi wireless school in Hull. Spent a bit of time afterwards sailing on lumpy water.

Regards

Mick

Definitely you should write your memoirs, Mick! Meanwhile, I’ve just posted an item which, in light of your adventures, may be of some interest: A Toton Sidings Sunday