WW2 wedding at St Polycarps, Wisewood: Uncle Reuben to bride Kathleen. Grandma centre right, next to bridesmaid Aunty Ellen.

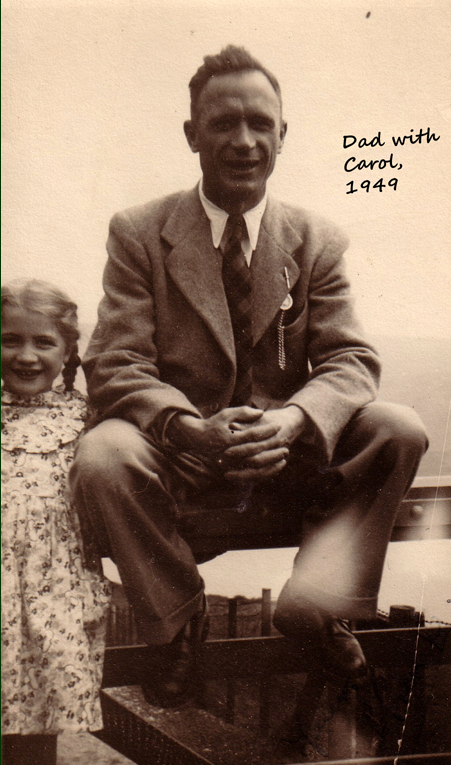

If my father (second left above) could speak out from the grave he’d take stern exception to my writings. Born in 1910 to Sheffield steelworkers two generations down from blacksmiths who’d migrated north from rural Bedfordshire, as the industrial revolution gathered steam, he was ten when the first motor car entered his Hillsborough street, fourteen on first seeing the ocean (at Cleethorpes on a Sunday School chara trip) and fifteen when, about to start a normal shift at an Attercliffe rolling mill in May 1926, he was stopped by the shop steward.

Tha can put thi tools down and get thi jacket back on, kid. It’s everybody out!

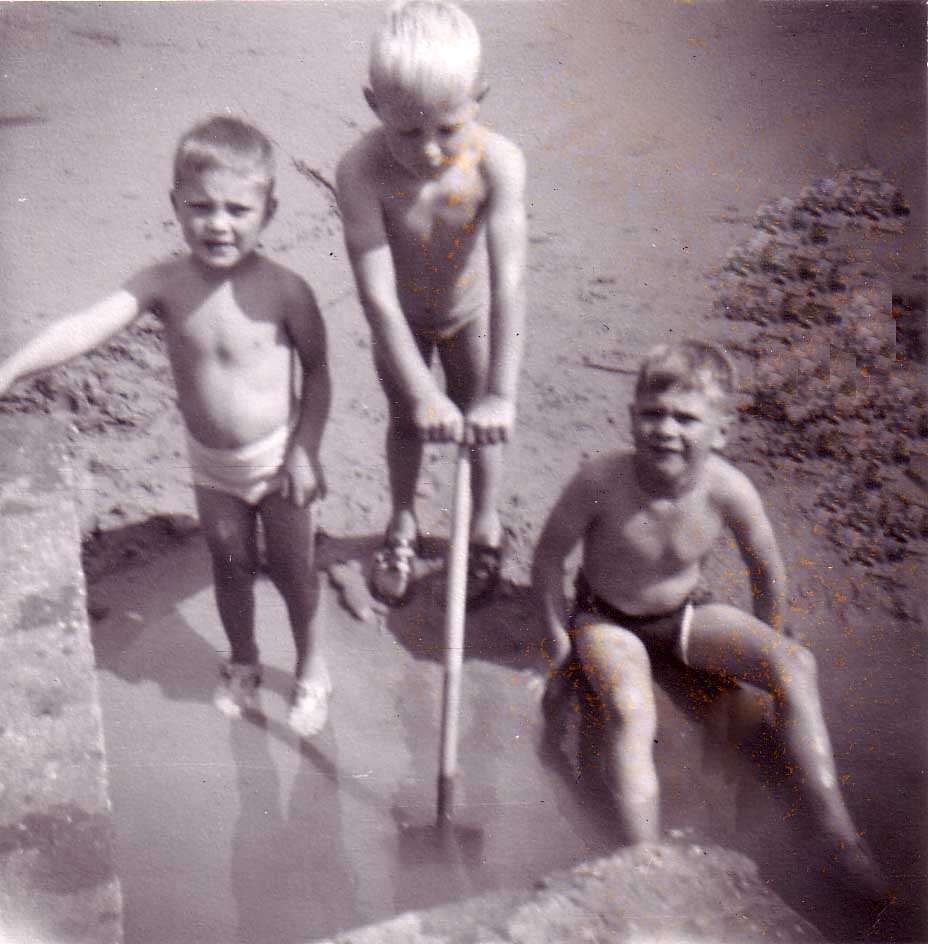

Dad’s life was no bed of roses. By the time I came into this world in 1952, eldest of three by his second wife, he’d lost her predecessor (big hat) to TB; a five year old firstborn (big hat’s little boy) to meningitus. When I was ten he’d lose that second wife to suicide, and their three boys would be packed off to a children’s home near Margate. But that’s a tale for another day.

For all dad’s trials and tribs though, life for a working man was looking up. These were the days of full employment, ‘Butskellism’ and Harold Macmillan wooing the working class vote with the strapline, “you’ve never had it so good”.

For us kids it was a world of polio jabs, school canings and welfare orange juice. Britain, tired and blitz ravaged, was gripped by austerity. We wore handmedowns and if we were lucky rode second or third hand bikes that weighed a ton. If they broke we fixed them, or pestered dad till he did. But we were and to this day still are in rude good health. We never went to bed hungry and, when illnesses came knocking, they did so as nuisance callers. Not as angels of death.

With mum at Sheffield lane Top, spring 1953

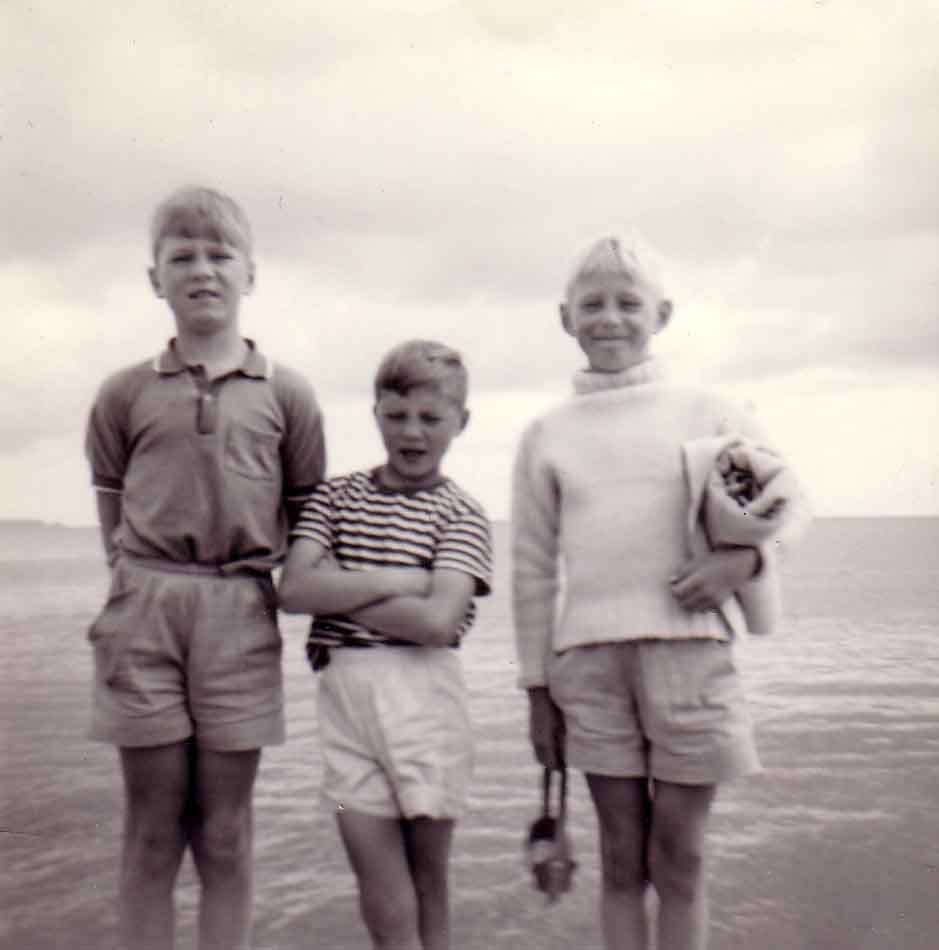

Most likely Bridlington on a day trip, 1959

Mum (with Uncle Deryck) in the summer of ’62. She died in April ’63

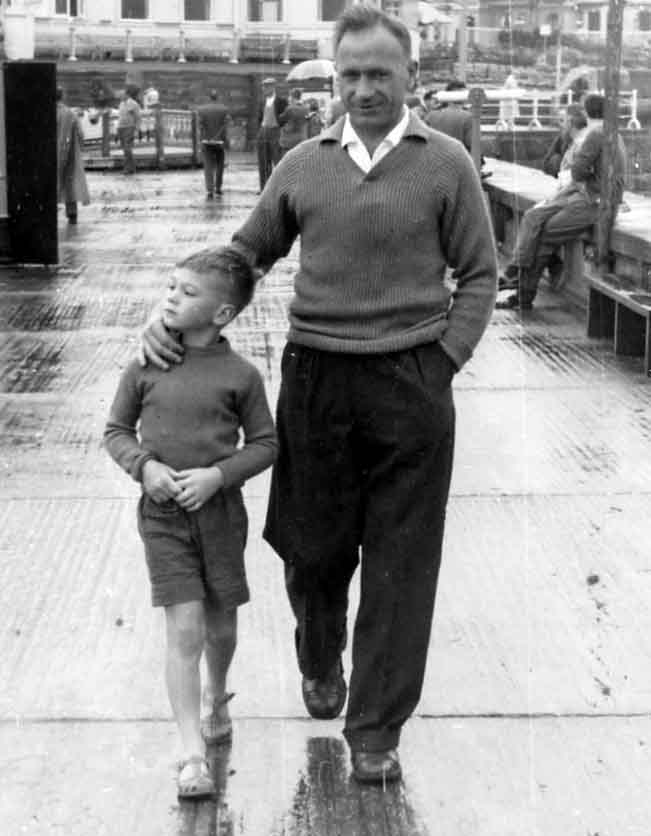

Dun Laoghaire, 1964. We’d been in children’s home nine months but dad had us for the school holidays

Ours was the Beveridge generation. We passed our eleven plus and Got On. Me, I ducked and weaved. I put that down in part to that tale for another day, in part to a throw of genetic dice that made me a waywardly introvert child who found his feet, as childhood gave way to youth then early adulthood, as a rebel with cerebral tendencies. I don’t say I was brighter than other kids. But I read more – show me the child who reads voraciously and I’ll show you a child on the run from disturbing realities – and by mid teens was asking questions my peers weren’t.

Bridlington, 1959

Indifference to whether t’owls won or lost of a Saturday didn’t boost my popularity any. Before I turned six, dad, who had nicknames for us all, had dubbed me “the prof”. It was a while before it dawned on me that this wasn’t the unalloyed compliment I’d taken it to be. On a Sunday walk around 1960 my half sister Carol, nine years senior, asked a question I couldn’t answer. With the theatrical air she specialised in, she halted the walk to make an important announcement.

Hey listen everybody. Our Philip doesn’t know something!

In 1964 I was a first year when my Broadstairs school sixth form held a mock election parallel to the one Harold Wilson won, without an overall majority. I voted Tory because I liked blue more than red but by ’71 was toking dope, doing acid, living in a commune and embracing anarchism.

I had three A levels though. After a year in India, four in diverse lowly occupations and two as a founder member of a wholefoods co-operative still trading, albeit no longer as a co-op, I slid into Sheffield City Polytechnic the year Mrs Thatcher defeated Mr Callaghan. On graduation at thirty, the woman I’d buddied up with on my course was carrying my elder daughter and I was a marxist, though not yet done – do any of us ever truly stop? – with the ducking and weaving.

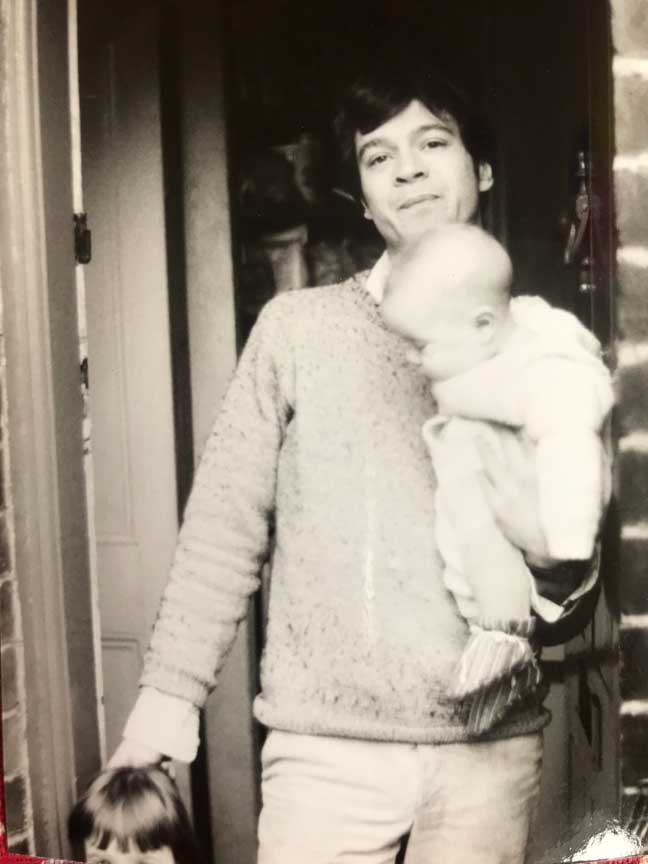

Father to be at 30, 1982

A graduate now, father of 6 month Annie, but not yet climbing the social ladder. House painting in 1983

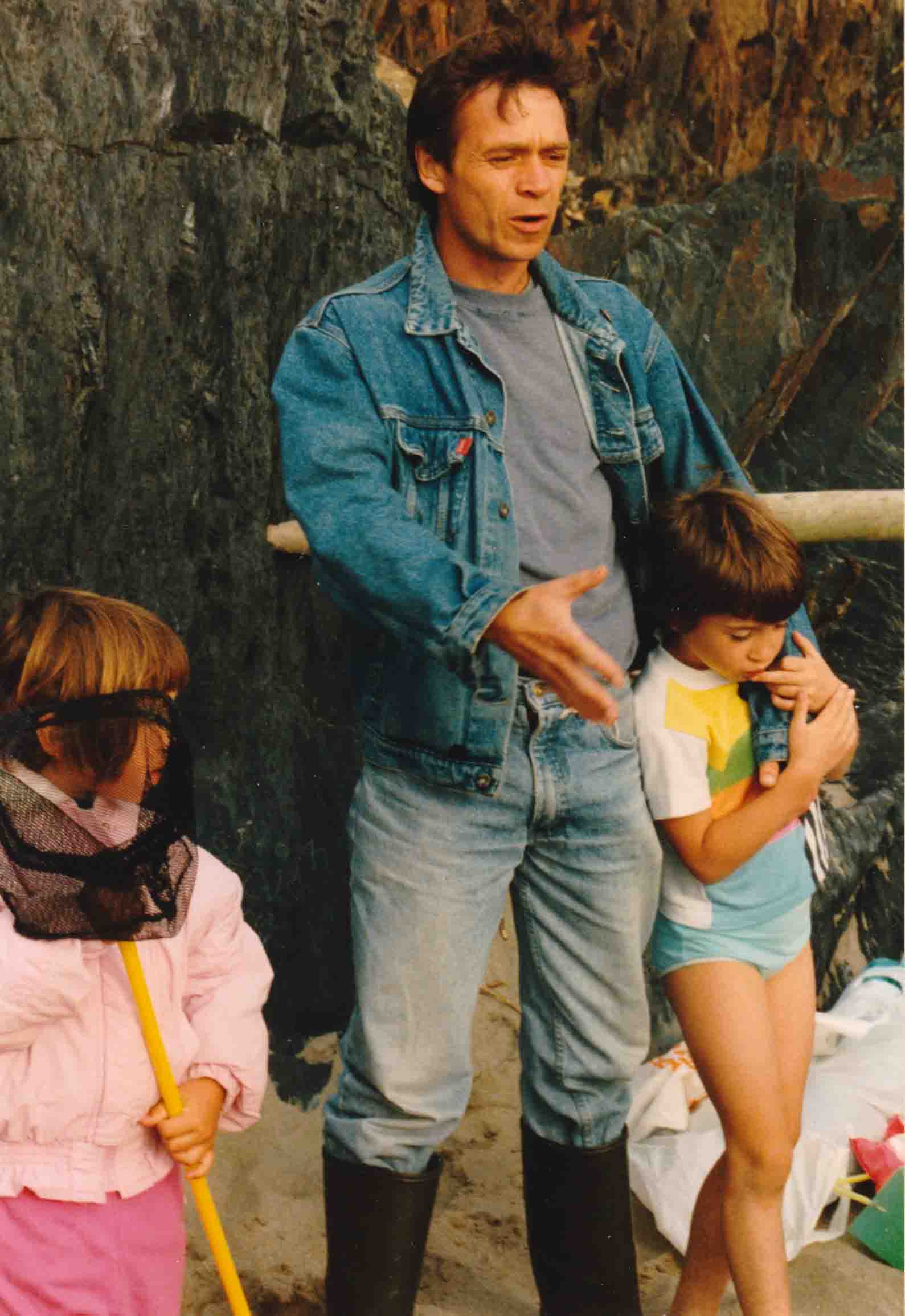

With Fran, baby two, in or around St Davids, 1985

With Fran and top of Annie’s head, Down to Earth Wholefoods, circa 1985

Sheffield, 1986

Holding (forth to) Annie as Fran looks on in or around St David’s, 1990

York 1995. Man, I loved that shirt!

Still, here I am at sixty-seven: middle class, own home, two grown up daughters, family car. I’ve accrued embarrassingly expensive camera kit, thrown in an inflatable canoe and done my bit for climate change by wandering four continents for no better reason than “to see the world”.

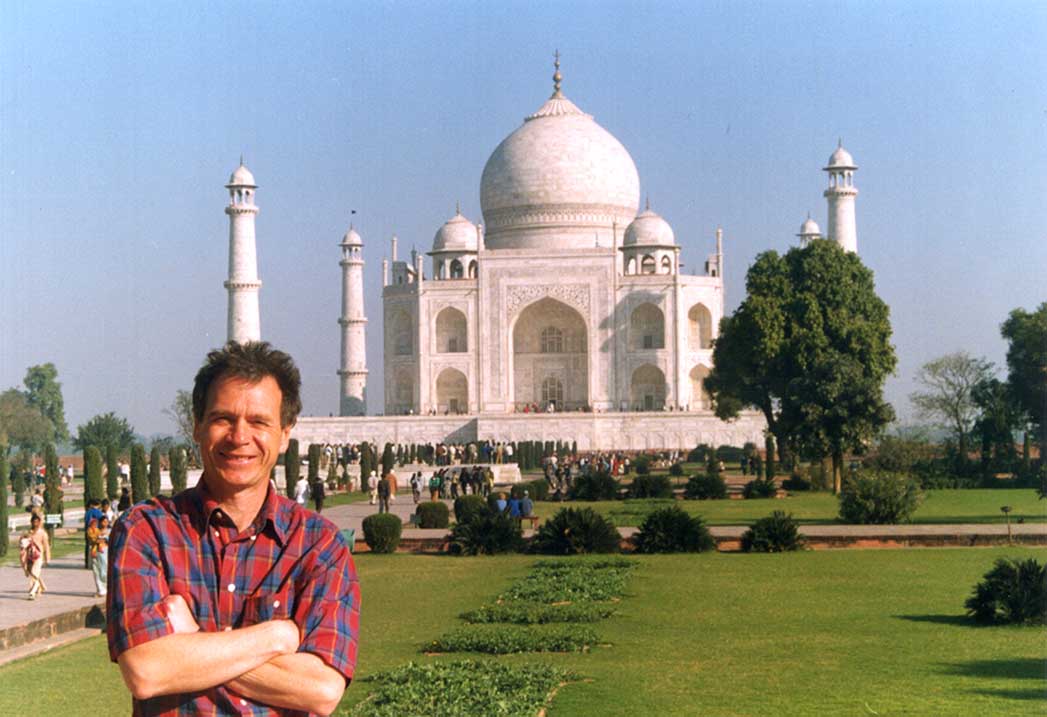

My first return to India in a quarter century, February 2000

NYC, 2001

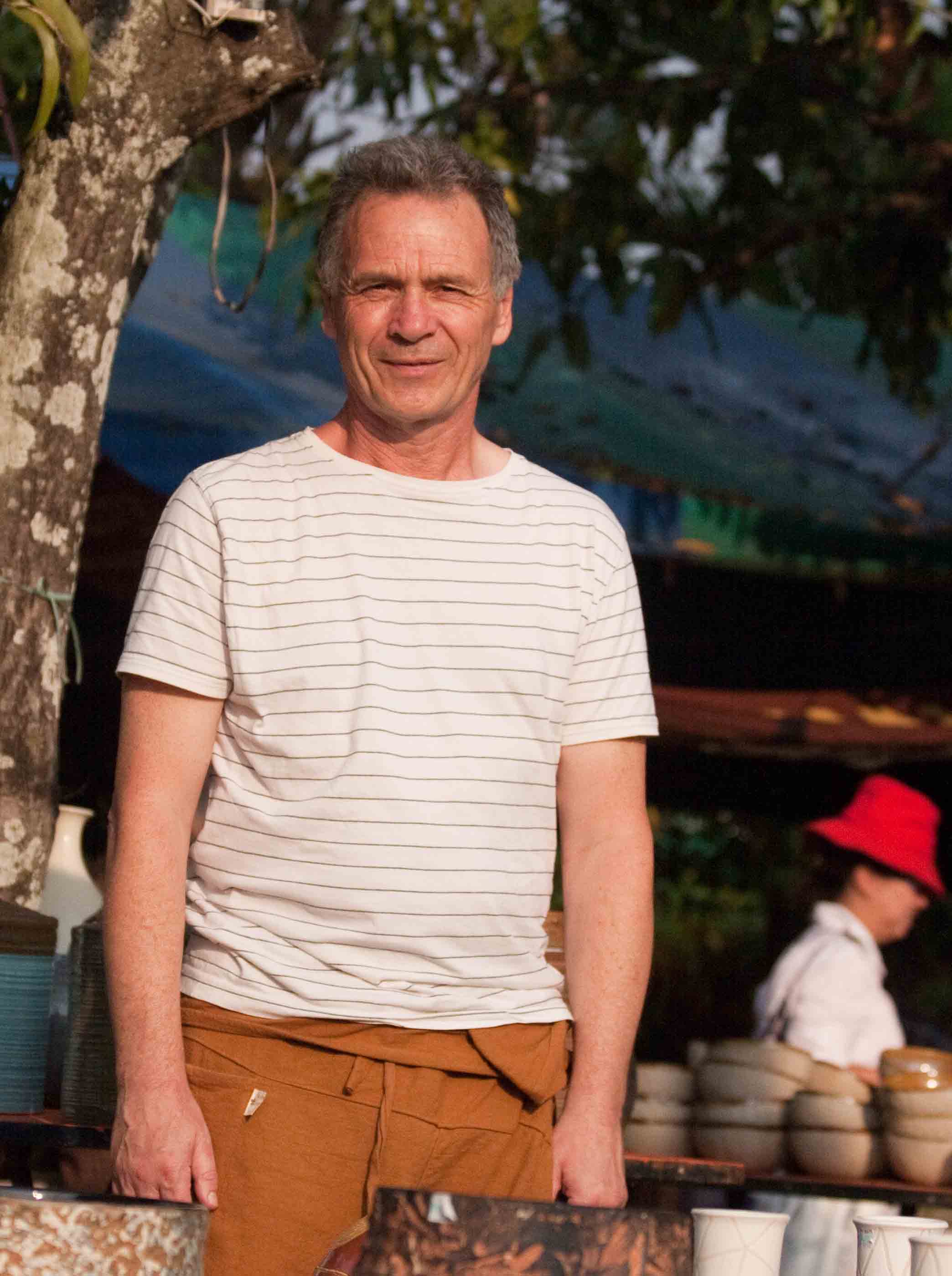

Village near Chiang Mai, Thailand, 2010

… and I’m still a marxist. Or more accurately, have returned to that persuasion.

“What the devil”, the old man would ask, were he in any position to do so, “gives you cause for all this griping and grousing?”

Dad had the class instincts and visceral grasp of realpolitik most manual workers have but, also like most manual workers, lacked what I call class understanding. He saw socialists as deluded: blind to the reality that any society must incentivise contribution to the whole, hence itching “to share out everybody else’s money”.

Such misconceptions are common, understandably so. Staggering inequality, the most glaring feature of class rule, is to marxists more symptom than cause of capitalism’s deeper madness. But the spectrum of ‘sensible’ politics is narrow; kept that way by a deep pocketed class with nothing to gain by accurately representing its ablest critics. Blogger Caitlin Johnstone nails it:

Powerful people think in terms of narrative control. Ordinary people don’t. Change that and you change the world.

“Good question dad”, I’d reply. “How long have you got?”

*

My opener was a fib. Dad has no grave. His twilight years spent in dementia, moved from care home to care home due to fits of paranoid violence common with Alzheimers, he was taken – an octogenarian but only just – by pneumonia at Middlewood Hospital in January 1991. That once muscular body a distant puff of smoke over Hutcliffe Wood Crematorium, its ashes sat for over a year in a garage – whose I don’t recall – while we got on with our busy lives.

On a gorgeous day in the summer of 1993 the two surviving children from Marriage One, three from Marriage Two, six grandchildren and a spouse or two gave those ashes to the four winds at Strines in his beloved Peak District. We watched them disperse on peat and purple heather, then went down to Low Bradfield where dad in youth had roamed and done his courting. There we laughed and remembered and played catch on the cricket pitch of that picturebook village, at the head of a Loxley Valley still dotted with drop forges, rolling mills and the dams that had kept them working.

Even in ’93 those mills and forges stood as ghostly ruins. Now they’ve given way to newbuilds whose north and west facing windows gaze upwards at fields, woodland and scenic reservoirs which still quench the city’s thirst. And beyond them? The moors my father had for six decades of Sundays tramped in rain and shine, with family and without.

Agden Reservoir, looking down towards Sheffield over Bradfield and Loxley Valley

*

Hi Phil – “Love in a time of Corona”? – does the current situation move us to such reflections? Some parallel thoughts about my Dad who’s dad was a postman in Grays, Essex and who became a printer until he partially severed nerves in his back whilst lifting heavy equipment at work; no support from employer or union, no compensation, but patched up by a skilled NHS and his own iron will to walk and play tennis again (having been told he’d be in a wheelchair for the duration). I too scattered ashes at spots beloved by him – Striding Edge and the Old Man of Coniston – he had been an avid walker, but on both occasions I misjudged the wind and added a slightly puzzling crunch (not being on a beach) to the butties of the ramblers ensconced for their lunches. He twice set up enterprises to do the printing he loved and twice was sold out by partners who used his skills and then sold the business from under him. He used to do letterheads and business cards for Rank Xerox and Decca, but I imagine they never guessed that they were produced in a cupboard under the stairs in a flat in south London. We had to move there after the Tories 1960 (?) Rent Act tripled the rent on the previous place overnight and in spite of my mum’s taking on the landlord and being dubbed a Communist for her efforts. Enough. Parents strictly Liberal and would probably have agreed with your dad, even though my grandma reputedly broke her umbrella over a fascist’s back in an East End street disturbance. I have some photos I was going to bring before ‘t restrictions, so I’ll email for your collection – you and daughters and evidence of a less cerebral occupation. Take care.

You might be right Paul. The unusual calm is certainly inducing more meditative moments, of which this post may well be a product.

I recall a cartoon in the Daily Express featuring an irate granny who did brolly violence!

I’d like to see your photos. I’ll see what I have of my little’uns.

A lovely post Phil. And I agree with the previous comment, “does the current situation move us to such reflections?” Ironically, in a time of plenty with “nothing much happening”, people can feel free to sink in to their own little private worlds. But those extraordinary recent events have kicked away the complacency and folk who normally wouldn’t speak to each other now are. I have made more phone calls to old friends in the last few days than in the month previously. And this upheaval has also snapped me out of that insular focus on my generation to consider the “broader picture”. I was incredibly lucky. I see now more forcefully than ever that most are not. As Springsteen said, to punctuate a performance of “Part Man Part Monkey”: “We’ve come a long way. And we’re going back”.

Thanks George. I sense the contemplative mood is fed by more than one factor but the unaccustomed quiet – no planes, no lorries and far fewer cars – is surely one. Another I think you point to; a pull to communion. I too am making more calls and using social media for one-on-one chats.

I’m a huge admirer of The Boss. That quote says so much. Bob Dylan once told his son that “Bruce Springsteen can sketch out an entire novel in just two lines of a song”.

I’m intrigued by this bit about your dad:

“He saw socialists as deluded: blind to the reality that any society must incentivise contribution to the whole, hence itching “to share out everybody else’s money”.”

I assume that this means your dad thought socialists were “idealists” who could not understand that everyone must be incentive-driven. Which, for capitalism, must of course mean that everyone must be appealed to in terms of monetary greed. And the complaint about socialists always wanting to “share out everyone else’s money” is such a familiar one. David McCallum (fine actor, crappy political views) liked to quote Thatcher’s “The trouble with socialism is that it soon runs out of other people’s money” This is a view that sees the generation of money as a purely private matter where the entrepreneurs are the “true workers” who, since they have somehow produced this money substance out of nothing, have every right to keep it.

Misconceptions about socialism are endless, as you know. Most pernicious – Marx took J S Mill to task over this (as I mention in my review of Tim Anderson’s recent book) – is the idea that capitalism’s inequities stem from unfair wealth distribution, rather than insane relations of production we’ve all come to see as normal.

In fact I’d conceived this post as a dialogue. Dad’s imaginary question was to be the means of setting out why, despite my enjoying a lifestyle beyond his wildest dreams, I say capitalism is an anathema. As it happens just one strand of my ‘answer’ would have taken in what your Springsteen quote alludes to: the fact postwar boom, welfare state, mixed economy etc – and hence the ladder I and many others used to climb out of the working class – was due to the peculiar conditions between 1945 and 1979, when cold war necessitated, and imperialism enabled, ‘caring capitalism’ in the West. Now we’re racing back to a new and frightening version of pure capitalism.

But try as I might, the project started to look clunkily didactic. I decided to leave the post as a series of laconic snapshots of two intertwined lives. The other stuff can wait.

But can there ever be such a thing as “pure capitalism”? Marx and Engels noted that capitalism was the most dynamic system that has ever existed – having no respect for any of those idols of the conservative (culture, religion, “the family”, tradition etc.) and also constantly pushing technology forward under the compulsion of profit maximization. It is an inherently unstable system. Ellen Meiksins Wood refers to it as “ the system that dies a thousand deaths”.

I suppose that most would link the notion of “pure capitalism” to the Dickensian days. But time is irreversible. Certainly, the rights and protections of workers gained after a long struggle can be – and indeed ARE being – reversed. But the brutal new world will not be on the old industrial factory model. The drive has generally been towards increasing atomisation.

And this seems to have received its most potent form with this virus – not that I’m saying that this was an “intention”. It just seems odd to me that the present situation with us all stuck in our little houses clicking away on Facebook and “going” to “watch parties” (virtual concerts) must be the ultimate in social impotence. Of course, once again I am speaking of my own rural situation.

Will this unprecedented situation be taken as a great opportunity for capitalism to reorganise society to its benefit?

Another thought: when capitalism is in crisis, it can be bailed out by state intervention. During the great depression, Roosevelt with his New Deal attempted to save capitalism – and was hated for it by the capitalists. They still abhor his “interference”. But the true end of the depression was the second world war. And it is a wartime economy that allows capitalism to provide state support – on capital’s own terms. Is something like that on the cards here?

I am seeing this virus situation in terms of how it can be exploited by the capitalists. But Marx stressed the dialectical angle i.e. that every situation has contradictions.

In the Dickensian days, there was a contradiction in the way that capitalism needed to create centralised collections of workers but that that very centralisation meant that workers could form their own armies against the system. One notable aspect of the current situation – and despite what I preciously said about the atomisation tendencies of social media – is that people, who would normally ignore each other, are starting to talk to each other. The media which is trying to scare everyone into isolation is actually forcing people to come together!

Phil, I’ve been thinking about your comment,

“Because I oppose capitalism, its defects exposed as never before in my lifetime, more than I oppose authoritarianism I’ve been inclined to bend the stick of doubt in favour of accepting covid-19 as “a real and terrible” danger.”

And I was musing on the matter of those subscribing to the skeptical view of COVID 19 being swayed by a libertarian view i.e. that they seem to be more fixated on the removal of liberties than in the basic matter of provision for all. This libertarian view has been expressed endlessly. We have heard over and over about the horror of a conformist state where everyone loses “individuality”. I was thinking of three figures who are certainly disparate: Peter Hitchens, Ayn Rand and David Icke. Frankly I would only describe one as a thinker: Hitchens. Rand had an outlook that was aptly described by a philosophical man, Brian Leiter, as “appealing to narcissistic imbeciles” and Icke is basically an opportunistic crank. But all of them express this dread of “the new world state”.

Isaiah Berlin had a biography of Marx that noted Marx had a deep loathing for exhibitionist bohemianism and felt it to be an inverted form of philistinism. The perfect example of such in Marx’s own time came from Mikhail Bakunin. And Bakunin has been held up by the Western propagandists as someone who “refuted” Marx by predicting the totalitarianism of the Soviet state and thereby showing that communism was alien to “human nature”.

And it is this libertarian/ anarchism/ bohemianism that has been idolised by the Western system. You can see it all the way through popular culture i.e. the wild rebel figure.

But, as I think you have implied, the emphasis on “liberties” re: the virus is not the overriding concern but the impact it has on everyone’s economic life and material circumstances. And, considering that these have been worsening relentlessly over the past 40 years, the virus may reveal capitalism’s weakness rather than being supposedly used as a weapon by it.

Hi George. Good points but I’d rather not continue this discussion here, though I’m as exerised by it as you. I’ve just posted on the difference of emphasis you point to in your closing words. Here it is.

A good, down-to-earth read combined with interesting family photographs. A fascinating glimpse into a rich and varied life. Thank you.

You’re welcome, CeeJay. Kind of you to say so.