Well of course it is! Same as there’s a rude word in Scunthorpe and a big cat in billionaire. Just look at the spelling of trouble, will ya?

But as you no doubt guessed, I refer to headlines like this from The Guardian, August 15.

Hard truth and just desserts? Or more wishful thinking ‘analysis’ from the empire’s staunchest liberal cheerleaders?

.

Two aspects of America’s proxy war on Russia (and on Europe) in Ukraine are now clear. One is that we have been massively lied to, and still are, about whose fault it is. (See my introduction to Dan Kovalik in An American in the cradle of the civil war.) The other is that while we have also been lied to on Russia’s assured military defeat, reality is fast catching up with our media, political and military castes.

Less clear is whether and to what degree Russia’s economy is hurting. Here are two contrasting views. The first is from Michael Roberts, a Marxist economist quoted before on this site. Though I find him wrong in his criticisms of modern monetary theory – for the same reason I had been wrong: a confusion of fiscal and monetary matters with the real economy – I appreciate his use of factual evidence. Writing yesterday, August 17, Michael was downbeat on the prospects for Russia’s war economy.

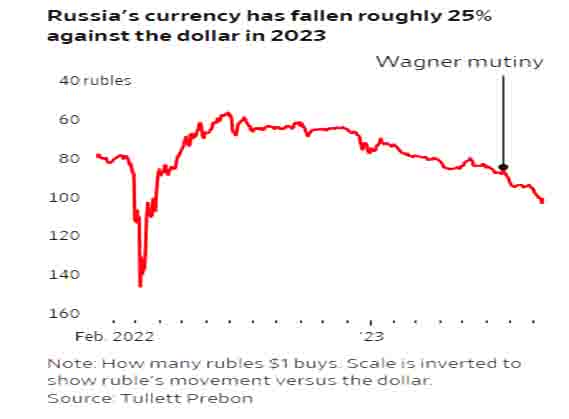

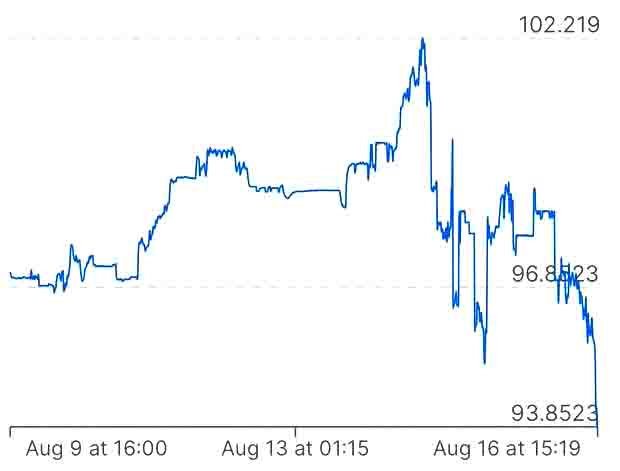

This week Russia’s central bank held an extraordinary meeting to discuss the level of its key interest rate after the Russian ruble fell to its weakest point in almost 17 months. The meeting decided to hike the bank’s interest rate for borrowing to 12% (up from 8.5%) in order to support the ruble.

The currency has been steadily losing value since the beginning of the year and has now slid past RUB100/$. That’s down 26%. The main cause of this decline is the fall in oil export revenues and the rising cost of military spending to prosecute the war against Ukraine.

When the Russian invasion began in February 2022, the ruble dropped to a record low of RUB150/$. Rich Russians took their money out to the tune of $170bn, most of which ended up in Europe’s property and banks.

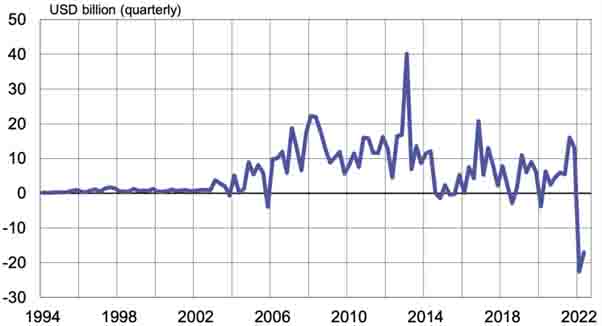

Russia: net foreign capital flows $bn quarterly

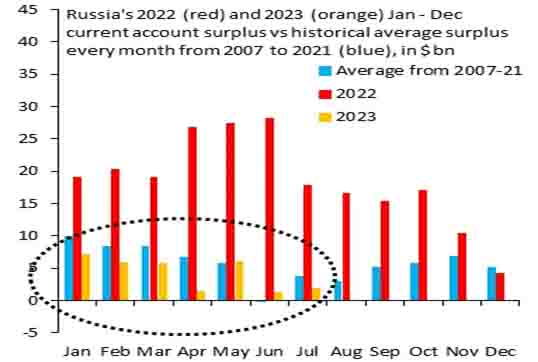

Weeks after Russia invaded Ukraine, a US official predicted that sanctions would cut Russia’s GDP in half. But that proved nonsense. It fell just 2.5%. That’s because the central bank introduced capital controls that stopped the flow of money from rich Russians out of the country. And as the price of energy rocketed over the next year, the ruble gained strength and reached a seven year high. Export revenues rose, while the sanctions and falling domestic demand led to a drop in imports, so Russia’s trade balance and current account rose sharply, bolstering the ruble. Two-thirds of the trade surplus was due to rising export revenues and one-third due to falling imports.

It seemed that sanctions on Russian banks and companies and a ban on using Russian energy had failed to bring the Russian economy to its knees. Russia was able to reroute its energy exports into Asia (if at a lower price) and find ’shadow’ shipping to deliver it.

But energy prices have slipped back in the last six months and the price cap on Russian oil imposed and enforced by the NATO allies has had some effect in reducing export revenues, while the costs of the war have increased. The 2023 defence budget is planned at $100bn, or one-third of all public spending.

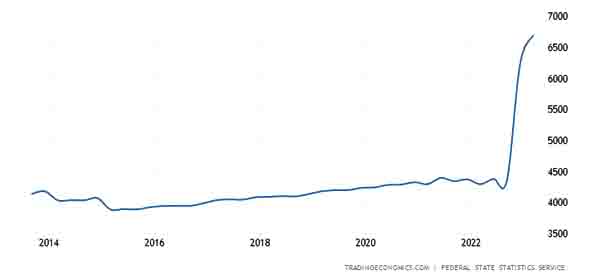

Government spending on the war, RUB bn

Russia’s national output rose 4.9% in Q2 2023 compared to the same period in 2022. That sounds good, but much of the rise in output has been in the production of military equipment and services. The output of “finished metal goods” ie weapons and ammunition, rose by 30% in the first half of the year compared with last. Production of computers, electronic and optical products also rose by 30%, while the output of special clothing has jumped by 76%. By contrast, auto output is down over 10% year-over-year. Russia is now a war economy. Russia has been able to import many of the goods that the West has banned—from iPhones to cars to computer chips—but it does so via third countries, a roundabout way that increases prices.

Immediately after the start of the invasion real wages for the average Russian fell sharply as the domestic economy dived. But energy revenues came through and low domestic demand kept price inflation low. As Russia workers were more and more employed in arms production or in the army, wages rose. In May 2023, real wages were up 13.3% year-on-year. Such an improvement no doubt helps keep support for the Putin regime.

But in recent months the energy revenue bonanza has fallen back. Russia’s energy export revenues are expected to decline from $340 billion in 2022 to $200 billion this year and next. Russia’s current-account surplus shrank to $25.2 billion in the first seven months of the year, an 85% fall compared with the same period last year.

At the start of the war, Russia had a large stock of financial assets ‘for a rainy day’. But it is now raining, if only as a drizzle. Russia’s National Wealth Fund (NWF) had savings and assets worth 10.2% of GDP at the beginning of the invasion. But that is now down to 7.2% as rubles lose value and war spending rises.

And the domestic civil economy and production is suffering. Sanctions are blocking technology imports and other key manufacturing parts. Some 65% of industrial enterprises in Russia are dependent on imported equipment.

But the impact of sanctions is slow burn. It may weaken Russian productivity and domestic production over the long term, but it is not going to stop the Russian war machine now and energy revenues to finance it. That could only happen if fast-growing Asia led by China and India refused to buy Russian oil and gas, but the opposite is the case – they are buying more at cheap prices.

Russia’s war machine will continue but as emigration of skilled workers and capital owned by richer Russians accelerates, it is weakening the currency and reducing available skilled labour in production.

Inflation had fallen in the last year due to the collapse in domestic demand and imported goods. But if the currency continues to dive, then it will start to rise, increasing the pressure on the central bank to raise interest rates to support the currency and try to curb inflation. A stronger ruble and higher interest rates would mean lower foreign currency revenues and a weaker domestic economy. That will hit Russian households hard.

As it is, potential average growth is probably no more than 1.5% per year as Russian growth is restricted by an ageing and shrinking population, with low investment and productivity rates. The profitability of Russian productive capital even before the war was very low.

The economics suggest that Putin can continue the war against Ukraine for several years to come, even taking into account the collapse in the currency and rising inflation and interest rates. Of course, that does not take into account political developments (like the Wagner revolt or gains by Ukraine’s NATO backed army). They could threaten Putin’s rule. And there are presidential elections in Russia next March – as supposedly there are in Ukraine. Both Putin and Zelensky must face the voters – at least theoretically.

But the underlying message is that the weakness of investment, productivity and profitability of Russian capital, even excluding sanctions, means that Russia will remain feeble economically for the rest of this decade.

*

Though my second writer shows no sign of being aware of that Michael Roberts piece, he is in fact responding to its central thrust: that the rouble has fallen sharply against the dollar. I’ve cited Simplicius the Thinker more than once of late, on the military progress of the war, and on the very different make-up of Russia’s central bank vis a vis the US Federal Reserve.

As a Russian patriot, Simplicius is biased. He’s also a realist who, like Michael, offers reasoned and fact backed argument to back his assessments. The words cited here are not a full piece but taken from the most recent (August 17) of his “sitreps” on events in the war zone. See Ukraine Commits Last Remaining Elite Brigade For Final Attempt.

Folded into his appraisal of the war’s progress, Simplicius writes:

There’s been a lot of talk about the Russian ruble and economy in general. Firstly, the central bank upped rates from 8.5% to 12% yesterday, which seems to have reversed the ruble’s crash for now:

.

But there’s an important thing which Andrei Martyanov highlighted in his new post as well. He mentions how Russia has dedollarized dramatically since 2010, implying the crash of the ruble matters even less now than ever. Furthermore, the Russian economy is currently booming, certainly supercharged by the defense industry which is on a massive hiring spree.

Many outlets report that Russia suffers a historic worker shortage currently. That’s true, Russia is having its worst labor shortage in “25 years” with ~40% of industrial enterprises suffering shortages. But the reason for this is overlooked: because Russia has too much of a good problem. Their unemployment is so low that almost everyone that can possibly be employed is already employed. If that was the U.S. or any other country, it would be reported with the fanfare of a major societal triumph.

Also, one has to be careful of what ‘shortage’ means. It doesn’t mean the businesses have no personnel at all, it simply denotes some form of staffing issues but in most cases those issues are not critical and are in fact minor inconveniences.

Martyanov’s post was in response to Larry Johnson’s own good post refuting an NYTimes hit piece on the Russian economy.

I’ll add to the discussion the following from a well-known Russian finance expert Pavel “Spydell” Ryabov, who explains the ruble situation in far more intricate terms. I’ll paste one section at a time and fill in the explanations, as I see them:

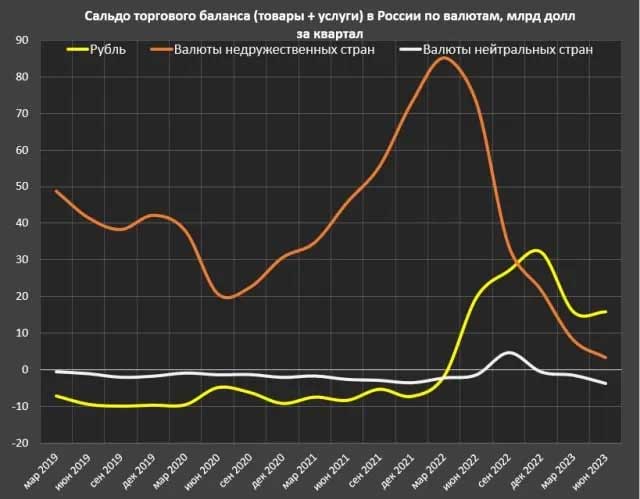

“The problem with the ruble is structural. The trade balance in Russia in foreign currencies (unfriendly and neutral countries) went into deficit for the first time since Q2 1998 – a symbolic $ 300 million per quarter, but a year earlier there was a surplus of $ 72 billion.

Before the start of its second quarter, the foreign trade surplus was about $ 40 billion.

This is big and good news. That means for the first time since 1998, Russia uses less foreign currency (deficit) in trade than its own ruble. Last year, according to these statistics, Russia used $72B more of foreign currencies.

At the same time, the trade surplus (goods + services) in the ruble has sharply increased, which in dollar terms amounts to $ 16 billion, both for Q1 and Q2 2023. The accumulated surplus from January 2022 to June 2023 in settlements with the ruble is almost $ 110 billion.

Now almost 40% of all Russian exports for Q2 2023 pass in rubles, compared with 14% in Q2 2021, in the currencies of unfriendly countries exports are about 34% vs 85% in 2021, and in the currencies of neutral countries exports increased to almost 27% vs 1% in 2021.

This is huge news. Not only does is Russia now using $110B more in ruble terms but 40% of all Russian exports for the current quarter are in rubles compared to 14% for the same quarter in 2021. In other words: last year, in all its trades, Russia used the ruble only 14% of the time to settle those trades. Now it’s using it 40% of the time.

Likewise, last year Russia used foreign currencies of unfriendly countries (presumably dollar and euro) in trade settlements a whopping 85% of the time and now uses them only 34%. The currency of friendly countries (presumably yuan, rupee, etc.) was used only 1% of the time and is now used 27%.

Putting the numbers together, this means that currently 67% of all trades are done in either the ruble or friendly currencies (yuan, rupee, etc.), while the remainder of trade—33-34%—is done in unfriendly currencies like dollar and euro.

About 30% of the turnover takes place in the ruble (29% before SVO), in the currencies of unfriendly countries – 36% (67% in 2021) and 35% in the currencies of neutral countries, compared with 4% in 2021.

Formally, foreign trade in foreign currencies is balanced (exports are equal to imports), but Russia was not ready to trade in rubles, not technically, but structurally.

Liabilities are formed in foreign currency on interest payments on foreign currency obligations, and the external debt itself is almost entirely concentrated in the currencies of unfriendly countries.

The outflow from the financial account is also mainly in foreign currency, with the exception of trade loans and funding advances for external counterparties of the positive balance of the trade balance in rubles.

To reduce the long-term pressure on the ruble, it is necessary to restructure the foreign currency debt, and these are years. Or to agree on the repayment of obligations in foreign currency in rubles, but they tried in 2022 and failed.

With a zero trade balance in foreign currency, any outflow of currency will destabilize the ruble, i.e., currency control measures are inevitable until the moment of “splitting” foreign debts.”

This gets into complicated territory. But the gist of it is that there are certain thorns in Russia’s financial haunch in the form of some of its debt being financed in unfriendly foreign currencies. And since such debt typically has a long term maturation attached to it, it can’t easily be converted back or refinanced into rubles, and all its attendant interest payments have to be made in the foreign currencies. This can destabilize the ruble when it’s sold off on foreign exchange markets to purchase the foreign currencies needed to pay off this debt.

Long story short: once the current dollar-denominated bonds are paid off eventually, the problem could be resolved as in the future Russia could choose to not issue such bonds anymore. But for the time being it has to pay them off via foreign currencies.

I don’t care to get into the specifics, but anticipating questions on it I’ll answer it briefly. For those wondering why Russia has dollar-denominated debt of this sort to begin with: to fund the federal/national budget in a time of deficit the Russian gov’t can issue either dollar-denominated bonds or its own “OFZ” (ruble bonds) which are purchased by various investors (both domestic and foreign). The money from these purchases funds the government budget, or the portion of it which was in deficit. The Russian gov’t now has to pay off those purchased bonds. The OFZ ones are paid off in rubles but the others have to be paid in foreign currencies as Western countries maliciously refuse to let Russia refinance them in different currencies for the simple reason of deliberately creating headaches for Russia.

But the overall point is that the east/west crisis of the past two years has allowed Russia to vastly dedollarize (I use that as a blanket term for all unfriendly currencies) which has some ‘growing pains’ associated with it, but which will eventually lead to unprecedented independence, particularly when coupled with the coming BRICS-led initiatives which will hopefully allow countries to grow progressively bolder in settling in their own currencies, if not entirely redesigning the system with a new BRICS currency of their own, which is the hoped-for long shot.

In the below chart from the same Pavel Ryabov post above, we see total Russian trade balance (goods + services) in billion dollars per quarter. Yellow represents rubles, orange is unfriendly currencies, and the white line is neutral currencies:

* * *

There seem to be all sorts of problems with analysis of this kind. From the assumptions of various competing models and their criteria to the selective use of what statistics to use and what not to use.

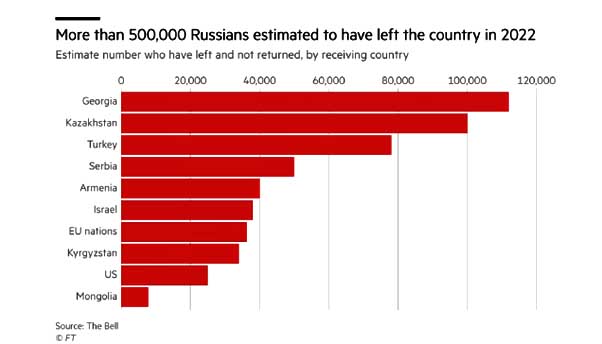

On that latter point some of Michael Robert’s chart’s and associated analysis/arguments miss out relevant data. Highlighting, for example, the number of Russians who have left the country [some half a million] provides a misleading picture simply because it ignores or omits the numbers coming into the country [with some estimates showing up to 3 million from the Ukraine alone].

It tells us nothing useful about the skills of those coming into the country because it fails to consider that key side of the equation. Which is basic math’s/mathematical modelling – both sides of an equation have to balance. Ignoring one side of an equation and only dealing with one side is not analysis. At best its sloppy modelling and at worst crude propaganda.

Ditto for the ‘high worth’ individuals – ie oligarchs’ who have left the country. On its own this, again, is insufficient for a robust analysis simply because it fails to differentiate – as Michael Hudson would doubtless observe – between different types of values – unproductive rent seeking financialised value and productive value.

Ignoring such variables and their impact on the economy will result in a less than robust conclusion on not only how the economy is performing now but also how it is likely to perform in the future.

Neither analysis, Roberts or Simplicus, tells us anything about the measurement criteria used. Is it pure traditional neo-liberal GDP? PPP? A mixture of both? Or some other method?

Moreover, looking at one economy in isolation ignores the wider comparative context of how that economy compares to other competing economies in the West. Just how is the Russian economy stacking up in comparison to the economies of the West? Not only now but in terms of trends based on an holistic rather than partial model to suit convenience along with more robust criteria and explicit stated assumptions. Without such context the analysis is limited at best and at worst redundant.

On that basis, despite the analysis provided in this link…..

https://www.leftbrainwave.com/2022/11/the-coming-european-economic-apocalypse.html

….being nearly ten months old it seems reasonable to claim that it provides a more comprehensive and robust analysis of the issue.

Good points about Michael Roberts – who always keeps his posts short – saying nothing of incoming and outgoing skills.

It’s your other point I’m less sure about:

Isn’t the thrust of the Simplicius extract that, just as GDP is a wildly inaccurate measure of economic strength (witness the FIRE led West’s spectacular failure to read the resilience and capacity of a country with a GDP the size of California’s), rouble performance against dollar, euro and other ‘hostile’ currencies is similarly a red herring? If so, the downbeat assessment of Michael Roberts is wide of the mark.

Granted, there are those like Yves Smith at Naked Capitalism who caution against hasty pronouncements, rooted in understandably wishful thinking, on a ‘dedollarised world’. (Even Michael Hudson, admired and often showcased on the NC site, is taken to task over what these friendly but more sober voices call an excess of optimism on the point. See in this regard an NC piece from December 22.)

So yes, there is a debate to be had on the extent and pace of dedollarisation, assuredly hastened by the US war on Russia in Ukraine but far from a done deal. Nevertheless, it seems to me wide of the mark to blame Simplicius for failing to do a job he never – or am I missing something here? – set out to do.

Apologies for being so late to the party Phil, I have been contending (thankfully not on my own!) with Storm Betty and her aftermath on a campsite on the Llyn with two little girls for the past week.

This is a very timely post. As you point out most attention has been given to the war on the battlefields of Ukraine, but now this is unfolding as a major disaster for NATO a shift appears to be occurring to consider the other major plank of the ‘Collective West’s’ assault on Russia – it’s attempt to take the Russian economy down. Articles like you reference are beginning to appear in the west’s mainstream media that are gleeful about the perceived weakness of The Rouble, the implications this may have for Russia’s economic future and the apparent support that this provides for the effectiveness of western sanctions.

Hmmm.

Michael Roberts’ analysis, particularly relating to the sudden hike in the Central bank interest rate, would be rightly concerning if applies to western neo liberal economies, but I wonder whether it is so devastating for an economy less heavily encumbered with credit and debt repayment. Moreover, Alexander Mercouris makes the argument that the Russian central Bank is highly interventionist in foreign exchange markets and manages the value of The Rouble to meet the needs of the overall economy. My memory of his analysis (sorry can’t reference) is that it has suited Russia to have an overvalued Rouble in the recent past and that it is now seeking to revalue downwards . The experience of all central banks is that this is not an exact science and the sudden, large hike in the rate would suggest that this process is not going particularly smoothly!

Despite this, Michael Roberts makes the point that Russian coffers are well able to withstand difficulties in the short term and will not impact on the country’s ability to continue to prosecute the war in Ukraine for the foreseeable future. This is the key issue for The Kremlin and indeed the majority of Russians who see NATO and the collective west as posing an existential threat.

Simplicius’ analysis puts any softness of The Rouble into the context of a rapid process of de-dollarisation – the value of the Rouble against US$ simply matters a lot less than it did. Russia is actively seeking alternative international trade payment systems through the development of BRICS – a process that will inevitably lead to disruptions in international trade across the board – one that will challenge all economies in the short term (and the west particularly in the longer term).

Michael Roberts suggests that the impact of western sanctions on Russia will be a ‘long burn’ (he doesn’t mention the ‘immediate burn’ of the impact on energy supplies to Europe) and no doubt the current reliance on a war economy will create difficulties in the future. However, I would be surprised if this issue has not been part of recent discussions with China – who will surely bankroll any required easing back to a peacetime economy in acknowledgement that it is, for the moment, Russia who is taking the ‘hit for the team’.

Finally, I think Dave is right to point out that any negative predictions for the Russian economy in the future need to be considered in the light of the prospects for western, neo liberal economies. Michael Roberts’ underlying message of ‘weakness of investment, productivity and profitability’ …. resulting in economic feebleness surely applies to Britain, Europe and the US too!

Great comment, Bryan. On the question of BRICS ascendance it’s clear that the actions of Washington – at the macro level its expediting of Russo-Sino friendship, and at the medium level its theft (directly or by vassal states like Britain) of the assets of states it doesn’t care for – are fuelling global south thirst for a de-dollarised world.

(As you know, Michael Hudson likens this to the Sophoclean tale of Oedipus, whose efforts to thwart destiny in the shape of patricide and incest only served to ensure those very outcomes.)

What’s less clear is how quickly such a world can emerge. The expansion of BRICS member states, and what Washington/Wall Street and their junior partners will do in response, is – if you’ll pardon an execrable play on words – the billion dollar question.