In Walking the Erewash I composed a limerick to steer readers past the pitfall of pronouncing the eponymous river as ‘earwash’. Pairing it with ‘very posh’ I thought to spare embarrassment, should ever you find yourself in that neck of the woods.

But what began as a heuristic device1 has taken on a life of its own, Yes, I’m afraid it’s true. I’m now an addict, in thrall to this deceptively simple verse form.

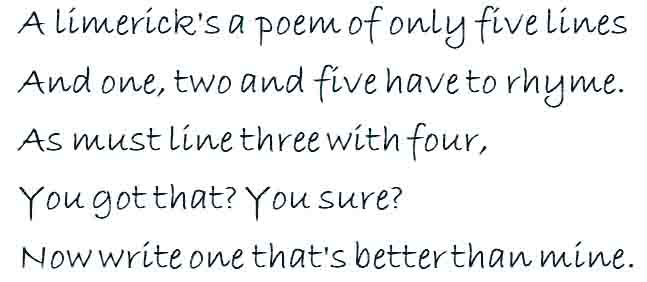

Some say the three long lines must have eight or nine syllables, the two short ones five or six …

… but that’s not entirely accurate, as this classic of the genre shows:

… but that’s not entirely accurate, as this classic of the genre shows:

Lines one, three and four follow that wikihow precept, but lines two and five have ten syllables. As for my own effort, the opening line has twelve syllables, though we can get the count down to ten by squeezing the word ‘limerick’ from three to two, and ‘poem’ from two to one.

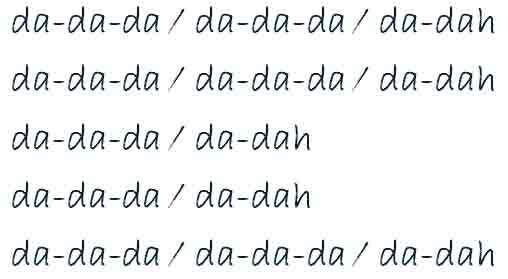

I reckon it’s best to rely on your own sense of rhythm. Verse structure is AA-BB-A, and the word music – as if you didn’t know – goes like this:

So how is it possible to get away with ten or even twelve syllable lines? The answer has to do with stress. Consider this:

Several things to note here. Though I say so myself, it trips off the tongue quite nicely. But how? The first line is nine syllables, the paired second ten. The third line has seven, the paired fourth just six. But you try evening things out – by removing ‘hot’ from line two, say. And by changing ‘Charlie’ to ‘Charles’.

It doesn’t work, does it? 2 But the biggest clue comes when you try – as I did while composing this last night (see how quickly we teachers become experts!) – to rejuxtapose those two verb phrases, “she moans” and “as she comes”.

What a pippy show! It’s as if, with the Cumberland Reel nearing its crescendo, the fiddler had seen fit to throw in a jazz lick of his own. The upshot is mayhem. The dancers collide.

It’s much the same with your tongue, even in the silence of the mind. The gear change from “as she comes” to “she moans” is harder than that from “she moans” to “as she comes”. Your tongue’s position – tongue’s position! – after “moans” allows a seamless segue, a downward arc that slaps effortlessly onto the “as”. Not so with “comes” to “she”. That tongue move, an upward arc, slows us down just enough to throw the line out.

How did I know this? I didn’t. All I knew, intuitively, was that my initial juxtaposition didn’t work but the final one does, despite syllable count staying constant. Only when I spoke to a pal in the smoke, a drama teacher, did I learn about the stress thing.

And when you think of it, just as a dancer fast on her feet might cope with that fiddler’s left-field move, so might a seasoned reciter make a virtue of that awkward, original juxtaposition in Ode to Mingus. But that’s not the point, is it? The Cumberland Reel’s meant to be footstomping fun for all, not an ordeal to snare and humiliate the doubly left footed.

And the limerick’s supposed to trip lightly off the tongue, as easy as the three line blues. Duke Ellington nails it: it don’t mean a thing if it ain’t got that swing.3

The bounce along simplicity – da-da-da/da-da-da/da-dah – hardly lends itself to serious topics, but you didn’t need me to tell you that either. Or that it’s a natural for pairing comedy and sex.4

So them’s the rules. They’re simple but the conundrums they pose are not. Don’t take my word for it: have a go. Writers will find it a splendid exercise. Writing is nothing if not the juggling of ferocious constraints. If you can come up with a decent limerick you’ll have mastered many – if not most – of its technical challenges.

Homework tonight? Complete this one.

* * *

- Speaking of heuristic devices, sex works equally well. See Sergey Merkurov’s 1931 response to the challenge of raising literacy levels in the USSR.

- Actually you can take out the ‘hot’ and you can switch ‘Charlie’ to ‘Charles. Arguably you’ll get a better poem. But it’ll take skill to deliver, and in my book that’s a no-no for a limerick.

- ‘Swing’ in a poem or song has more to do with enunciation than words on paper. In my response to Germaine Greer’s dismissal of Bob Dylan’s lyricism, I said: “a song’s meter is driven as much by the music, and in Dylan’s case unpredictable phrasing, as by the word forms … Ezra Pound, a fine critic when taking time out from cheering on fascism, made the points that poetry loses its way when too far from music, and music loses its way when too far from dance.” Even those two lamentable linesmen, K.Tynan and Dylan T (aka Cheech & Chong: see comments) have a valid point, though it’s not in their nature to desist from labouring it to death with that ‘mere mechanics’ gibe. Subtler students of the genre may with some effort extract, from the crude ore of their nuance-lite understanding, a modicum of truth.

- My use of “rude” in the title, and “transgressor” in one limerick, may raise eyebrows. Changing attitudes in the sixties generated the idea, with which I have sympathy, that all talk of sex as ‘naughty’ is life-negating. Massive subject, but objections to sex-as-naughty often have a puritanism of their own, an overly cerebral ‘liberation’ mirroring judaeo-christian prudity. Our enjoyment of sex-in-humour, from Chaucer to Carry On Up The Khyber, draws deep from those shared taboos.

I’ve got an old mate called Phil

His pretentiousness makes you ill

He’s plausible and slick

But sadly a dick

His writing is nothing but swill

Promising effort for a tyro, KT. But allow me two small tweaks. You’re a syllable short in line one. Replace “old mate” with “acquaintance”

Ditto in line two. Insert “quite” between “you” and “ill”.

There. Fixed it 4U.

There is an old man called Roddis

Trite and tiresome his prose is

His verse is much worse

The lines sound like a curse

And the poor weak rhymes are all his

This is doggerel, DT. Won’t do at all. It’s almost as if you and KT were one and the same third rate rhymester. Normally I’d give this a straight fail and move on, but out of the goodness of my heart I’ll lick it into shape.

“I’ve heard of an old man named Roddis

Trite, tiresome and turgid his prose is.

His verse is much worse,

Those lines are a curse.

And the poor sickly rhythms are all his.”

You’re welcome.

Ah I see you’re trapped in the mere mechanics and have yet to understand how flexible English vowels are. Strange for one who is confined in that terrible country.

Ha! I suspected you two varlets of versification would hook up sooner rather than later. (See footnote 3.) Mediocrity has a way of finding its shadow. Still, as Buddha says to Karl Marx (Discussions on Dialectics, Vol 3: Chapter 68) even mediocrity can inspire greatness:

A purveyor of doggerel named Tynan

Could ne’er pen a scannable line and

His bile made him bitter

As readers did titter

His only recourse was to whine on.

As for my being “confined in that terrible country”, well, where to start?

One, confined nowhere is I. Since I’ve roamed on four continents this past decade, my more recent confinement has been an ethical choice – it’s the air miles thing you see – making the even more recent lockdown quite irrelevant on that front.

Two, if by ‘terrible country’ you refer to the political situation, well, though it paineth me to say so, thou speaketh through thy bum. All countries are blighted – yours as much as any and more than most, whether you call it Catalunya or Spain – by class rule. End of.

Three, if by ‘terrible country’ you refer to aesthetics, well, though it paineth me further yet to say so, thou speaketh tenfold through thy bum. Check out “Britain” in the Travel section of the masthead menu.

Four, I have to go now. It’s been lovely putting you straight on matters versical but I fear I risk neglecting the sagacity of Proverbs 26:4. In plain English, the advice there is not to argue with fools.

Love, peace and poetic improvement (I’ll always be there for you on that last with the tough love of my incisive criticism) from the Steel City Scribe.

Darling Bobby was a folk violinist

When we rolled on the floor

I’d invariably insist

He must finger me more

Than his fiddling had yet to explore.

Ah. You’ve introduced a new verse form, LilySuze. Eagle-eyed readers will have detected so violent a sundering of the limerick’s constraints!

An old pond!

A frog jumps in—

the sound of water.

Matsuo Basho, 1684

Your limerick fonts are obscure.

Illegible? Yes. That’s for sure.

Calisto is better,

A much clearer letter

so then we can read you once more!

My font is quite rightly berated

But my subject, you see, is X-rated

I’ve moved from black Quink

to invisible ink

While I ride out the storm it’s created.

Please excuse the nauseous flattery.

There was a young scribe from steel city

Whose prose is concise and quite pretty

He quotes Karl Marx

In clearings and parks

And gets through to the real nitty gritty

Steel city scribe young? Why, good heavens!

Last autumn he hit sixty-seven.

But there’s life in him yet

Though he tends to forget

Where he last stashed his cannabis resin.

Last line of limerick homework.

Squeeze de breast, right and left and de-Bum.

I grew up near Rotherham so I know what I’m talking about.

Excellent! (Sorry for late response – I only just saw this Molly.)