Mull a moment, if you will, on the above. Generation-Z, aka zoomers, were born between late ’90s and early 2010s. As such the Western subset – the one for which, when all is said and done, the term was coined by marketeers and adopted by sociologists – inherit a world of diminished expectation. It’s true that the two previous generations – millennial parents who Occupied Wall Street, and baby-boomer grandparents who marched at Aldermaston and founded Friends of the Earth – were fearful for humanity’s future, but for the baby boomers and to lesser extent the millennials, generalised fear co-existed with levels of personal security the lower nine deciles of zoomers have no realistic hope of attaining.

And they know it. As a matter of fact one of the reasons I, a mid-term baby-boomer, am drawn to the Swiss option is that I’ve no desire to be looked after by people underpaid, undertrained and harbouring an entirely understandable grudge against my generation.

In the face of which I don’t suppose my arguments – assuming I wasn’t too doolally-pip even to make them – that they should wage class war, and not a war of the ages, would cut mustard or butter parsnips; far less spare me the abuses and indignities attendant – I speak from childhood experience – on being cared for by folk who do not love you.

Like race, gender and other exploited divisions of identity, those along age lines are neither to be ignored as ‘diversionary’ by an “old Left” gripped by narrow economism, nor metaphysically divorced by the ‘woke’ from the exigencies of class in its oppositional sense; in this case those of a West run by and for rentier oligarchs.

I refer to recklessly self-centred and short-termist choices, by said rentier oligarchs, which even as they propel us to nuclear and/or environmental catastrophe also, scorpion and frog fashion, hasten the decline of that which enables rentierism – a decline for which the zoomers will pay an obscenely unfair price.

My cue to hand over to the transcendental Yves Smith at Naked Capitalism. Today she dives, with that balance of incisiveness and nuance which keeps me coming back for more, below the superficiality of a nevertheless useful Wall Street Journal piece, also today, on The Rough Years That Turned Gen Z Into America’s Most Disillusioned Voters.

Young Voters, Victims of Neoliberalism, Pessimistic About the Future, Sour on Politics…As Officials Tell Them to Eat Statistics

I hope readers will indulge me in yet another careful reading of a thematically and in some ways informationally important article. These pieces often wind up saying as much about conventional and/or official thinking as they do about the topic. The object lesson today is The Rough Years That Turned Gen Z Into America’s Most Disillusioned Voters in the Wall Street Journal.

Mind you, the generational cohort focus already obscures more than it reveals. Class mobility has collapsed in America. Members of the top 1% and top 10% have more in common with each other than with the members of the marketing-designated age category. And if you read the Wall Street Journal article carefully, you can see it focuses on the experiences of the non-elite, which it politely does not call the masses. The article includes polling data, which would hopefully would include some in wealthier cohorts.

But the vignettes are all of under 30 year olds with modest jobs. The lead vignette is about Kali Gaddie, who had her plans upended when Covid hit in her senior year of college. She is now earning under $35,000 a year as an office manager in Atlanta (the article does not describe if she had higher aspirations and if so what they were). The article depicts her main personal interest as TikTok, where she has thousands of followers. The Journal notes:

Now, that’s at risk of being taken away too. All of this has left her dejected and increasingly skeptical of politicians.

The other featured characters are

-

- Noemi Peña, employed in a juice bar in Tucson

- Corey Darby, who last his first job as a newbie recruiter due to the pandemic and had it take a full year to land another recruiter position at $55,000 a year

- William Broadwater in Waynesburg, Pa, who had wanted to be a machinist, had a key test cancelled during Covid, then landed at a convenience store before becoming an HVAC technician and getting training as an electrician. But his erratic income means he still lives with his parents

- Audrey Lippert, who works part time at her campus Starbucks for $14.65 an hour: “She can’t fathom achieving the milestones her parents have.”

- Matt Best, who lost a year of work due to the pandemic, voted for Trump in 2020 but won’t again due to 1/6 but is also opposed to Biden by reason of his age and favors RFJ, Jr.

The story quotes two other named individuals to demonstrate that they get their news from non-traditional sources, such as Joe Rogan.

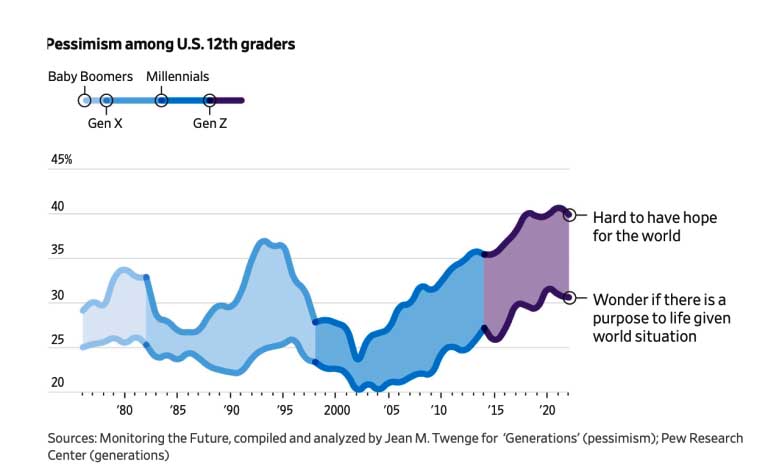

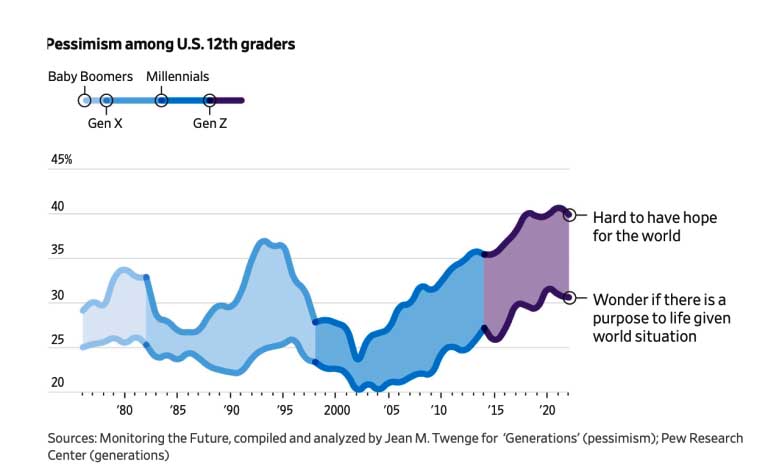

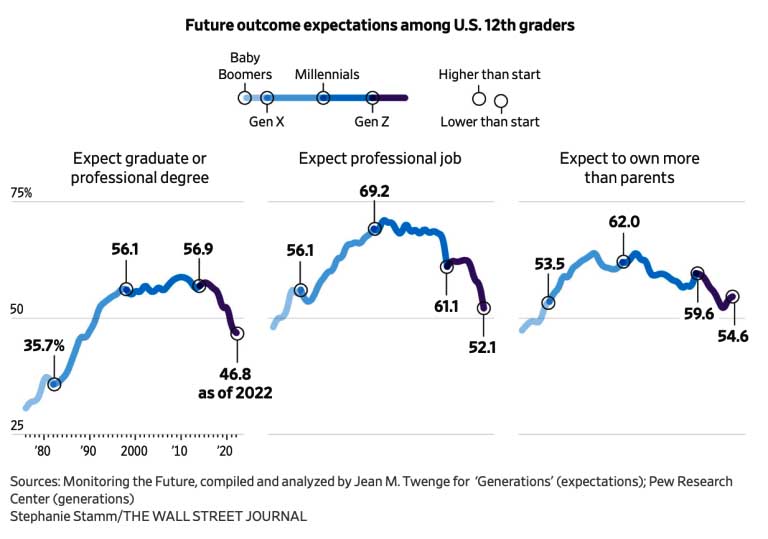

These charts present the main point of the piece:

Needless to say, that translates into a dim view of government and the mainstream media.

Nowhere does the article mention climate change as a cause for dejection among the young, including the better off. I know people a generation behind me who struggled over the decision to have kids: “Do I want to bring them into a world that could be coming apart societally? Do I want to contribute to more consumption by having offspring?” I’d imagine that that concern is even more prevalent among young adults.

We’ll highlight some of the critical finds in the article, such as the confirmation that TikTok is very important to the young. The proposed ban is providing them with yet more confirmation that the government does not care about their needs. The story dances around the idea that the bill to ban or force the sale of TikTok might be significantly about censorship, to curb their ability to confirm with each other how bad things are, as in how authority has failed them. Of course, since we live in the best of all possible worlds, any such thinking must be the result of Chinese trouble-making, as opposed to their experience.

The article focuses on economic data, like average wages and unemployment levels, and attempts to use that to understand why Gen Z voters are in “To hell with all of them” mode. But the effort to ‘splain why the young are dispirited come off, unintentionally, like “Let them eat statistics.” The story, unintendedly emulating macroeconomic models, depicts the sour mood among the young as the result of shocks, most of all the pandemic. It does not consider the deteriorating baseline, both in terms of real incomes and social stability. To illustrate:

The pessimistic mood contrasts with what in many ways are relatively healthy economic circumstances. Many millennials—those born between 1981 and 1996—started careers around the 2007-09 recession. Gen Z workers are entering the labor market during a historically strong stretch.

For the last year, the unemployment rate for those in their late teens and early 20s has averaged near its lowest in at least a half-century, according to the Labor Department. Student debt has fallen as a share of income, with the Biden administration canceling $138 billion in federal student loans. More under-35-year-olds own homes than before the pandemic. Young people have been hit by inflation, but by some measures, less than other age groups, according to a survey of consumers by the University of Michigan.

Young people say there’s plenty of evidence to the contrary. Among adults under 30, credit card and auto loan delinquencies are increasing. Savings have dwindled since reaching pandemic highs.

Rent has more than doubled since 2000, far outpacing the growth of incomes over the same period, according to Moody’s Analytics. More young people spend 30% or more of their income on rent than any other age group.

A Wall Street Journal poll conducted last month found more than three-quarters of voters under 30 think the country is moving in the wrong direction—a greater share than any other age group. Nearly one-third of voters under 30 have an unfavorable view of both Biden and Trump, a higher number than all older voters. Sixty-three percent of young voters think neither party adequately represents them.

For instance, the deterioration of average worker buying power over time has been profound. One reader described how at a modestly paid, starter working class job in the 1960s, he was able to save enough to buy a car in not that many weeks (as I recall, 12 or 16). Lambert, whose first real job was in a mill, earned enough to rent an apartment within walking distance of work, eat at a higher than cat food and spaghetti level, and enjoy regular entertainment, including buying lots of books and going not infrequently to Grateful Dead concerts. Lambert confirms was living modestly but not anxious about being able to make ends meet, in part because

Another factor lost in the comparatively narrow time window (odd given the use of generational cohorts) is the way social bonds and communities have eroded over time, and how those bonds once were meaningful part of social safety nets. My mother was born shortly before the Great Depression. Her parents lost all of the money they had in three different banks, save a 3% recovery from one, and their house. Yet she said that the Depression was not that bad, that people really pulled together to help each other.

That impulse is sorely missing today. From the very top of the piece, about office manager Kali Gaddie:

Kali Gaddie was a college senior when the pandemic abruptly upended her life plans—and made her part of a big and deeply unhappy political force that figures to play a huge role in the 2024 election season….“You would think that there’s a plan B or a safety net,” she said. “But there’s actually not.”

So even though the article stumbles upon the shallowness of formal support or enough not-to-hard-to-find backups as a key, perhaps central, element in why young people are disheartened, it then fails to follow up on the finding, perhaps because the reporters are too deeply indoctrinated to question neoliberalism.

For instance, job stability and average job tenures are vastly lower than they once were. Career churn has a cost. Losing a job or even getting a new one is a high stress event.

Similarly, the fact that jobs are generally available does not translate into a worker necessarily being able to find similar or better pay and other workplace conditions elsewhere.

Nor does the article consider that employers, particularly in modest or middle-wage jobs, are on the whole much more indifferent to their staffs’ emotional well-being. Intensive employer supervision and productivity demands are demeaning.

The article spends a great deal of time contemplating what this means in terms of voter behavior. It is revealing here that it hews to standard tropes. Nowhere is it willing to consider that neither party has been terribly attentive to the concrete material conditions of the fallen middle class and lower class. But from that would follow an uncomfortable corollary, that a political system set up to strip mine ordinary worker (albeit gradually over time) via medical industry grifting, a hypertrophied, underperforming arms industry, skyrocketing higher education costs, and real estate rentierism might not be appetizing to voters on the receiving end. They lead with TikTok as an illustration of warped priorities:

Young adults in Generation …worry they’ll never make enough money to attain the security previous generations have achieved, citing their delayed launch into adulthood, an impenetrable housing market and loads of student debt.

And they’re fed up with policymakers from both parties.

Washington is moving closer to passing legislation that would ban or force the sale of TikTok, a platform beloved by millions of young people in the U.S…

“It’s funny how they quickly pass this bill about this TikTok situation. What about schools that are getting shot up? We’re not going to pass a bill about that?” Gaddie asked. “No, we’re going to worry about TikTok and that just shows you where their head is…. I feel like they don’t really care about what’s going on with humanity.”

That seemed promising but then we get hackneyed concerns, such as social media as an amplifier of worry:

Gen Z’s widespread gloominess is manifesting in unparalleled skepticism of Washington and a feeling of despair that leaders of either party can help. Young Americans’ entire political memories are subsumed by intense partisanship and warnings about the looming end of everything from U.S. democracy to the planet. When the darkest days of the pandemic started to end, inflation reached 40-year highs. The right to an abortion was overturned. Wars in Ukraine and the Middle East raged.

All of the turmoil is being broadcast—sometimes with almost apocalyptic language or graphic video—on social media.

Dissatisfaction is pushing some young voters to third-party candidates in this year’s presidential race and causing others to consider staying home on Election Day or leaving the top of the ticket blank.

However, despite the hand-wringing about the profound unhappiness among the young, the picture the Journal paints is actually very reassuring to the elites. Despite the ever-growing concentration of income and wealth at the top, they have done a effective job of subjugating the poors via atomization and economic insecurity. The Journal, and here this rings true, depicts the young as too demoralized to get angry and take concerted action to force change.