For the second time this week I’m replicating a column by tax specialist and modern monetary theorist Richard Murphy. Here (lightly edited) is what he wrote yesterday.

Why interest rate rises are fuelling inflation

I have been suggesting interest rate rises are fuelling inflation.

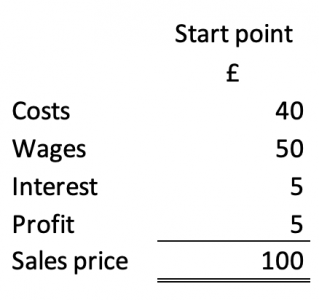

That idea might shock the Bank of England. They seem to think inflation is down to excessive pay increases but I have news for them. Employees do not set price increases. Companies do that. So let me put forward a model of a company that is largely service-based to explore my suggestion. This is the starting point:

The figures are for purely representational purposes (thousands, tens of thousands, or millions: it makes no difference). The proportion of wages suggests it is service orientated, as most companies are. 1

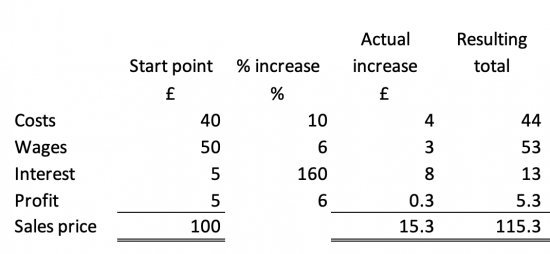

Then I suggest that adjustments for inflation be taken into account, as follows:

Bought-in costs have increased by 10% – roughly the rate of inflation in the last year.

Wage increases have been kept to 6% – which will be tough on many staff.

The big increase is in interest costs. The company pays interest at 3% over bank base rate. So, the rate has grown from near enough 3% to 8%, or a growth of about 160%.

In comparison, profits have only been targeted to increase at the same rate as wages.

The resulting overall cost increase is 15.3%, with more than half of that being due to interest, which imposes a bigger cost increase than external costs and the wage settlement combined.

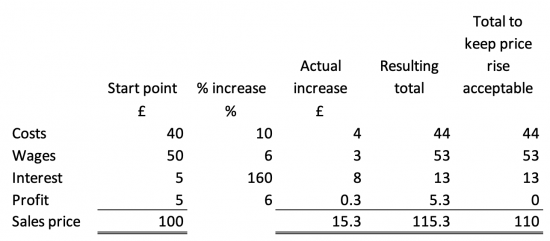

Let’s presume the company realises that the market will not accept a 15.3% price increase, and it keeps it to 10%. This is the result:

Profits have now been eliminated. The company’s future is, then, in doubt.

I stress that this is a model but the assumptions seem fair, as does the cost structure, although these (of course) vary widely.

My points are threefold. First, it is not wages that are driving up inflation.

Second, it is interest rate rises that are driving up prices.

Third, interest rate rises are now so extreme that many businesses face the threat of failure.

The Bank of England is welcome to use this model and think about the consequences of what they have created. I suspect they will not. What it makes clear is that we face a crisis created in Threadneedle Street, but they have no understanding of that.

And that’s why we face desperate economic times.

* * *

- The professor makes no comment on most (Western) companies being service oriented. This points to a greater flaw in his understanding. On the nail as his takes often are, they remain painfully constrained by his failure to grasp the nature of imperialism. Most firms are service oriented because Western capital, of necessity ‘unpatriotic’, has exported manufacturing to the Global South. (My post of six years ago, Economics of imperialism, focuses on the implications for imperialised nations. More recently, thanks in large part to the analyses of political economist Michael Hudson, I have switched my attention to the implications for the FIRE-led economies of the imperialist West – and for whatever future humankind may have.) Richard combines a sharp mind with a pithy style. He has access, via modern monetary theory, to truths – on the relationship between a national economy with a fiat currency, and its monetary and fiscal policies – beyond the ken of mainstream economists of monetarist or Keynesian stripe. But his failure to factor in the exploitative relations between West and Global South leads him to misread the nature of current tensions between the US and Eurasia. This in turn misinforms his superficial and grossly wide of the mark grasp of what is happening in Ukraine, and of why European and Antipodean leaders – in effect compradors – act against the interests of their own peoples and businesses as they seek dutifully to advance those of Washington and Wall Street. More to the point here, Professor Murphy – an intelligent and compassionate man – frequently shows signs of awareness of the class war Britain’s rulers are waging in the name of ‘austerity’. (And will continue to wage under a Labour government, as he has in other posts acknowledged even if he avoids that precise formulation.) In due course his integrity may lead him to a fuller critique of capital in the age of imperialism. Until then I say his insights – which I’ll continue to promote on this site – must be weighed alongside those of economists au fait with a bigger picture.

I have very poor understanding of maths and economics. One thing I don’t understand is that for most of my life (73 years) interest rates (and I can remember this) have been reasonably substantial, yet things were broadly not much different in essence from what they are now. Historically interest has been between 4% and 10% since 1720*. It has only been in the 0% to 2% in the last 15 or so years. So why is this latest rise seen as being so traumatic?

* See https://www.businessinsider.com/chart-5000-years-of-interest-rates-2015-9?r=US&IR=T

On the face of it your question is easily answered, Jams.

First, you have to realise that Business Insider – like The Economist but more so – puts out the most specious drivel on matters central to ruling class interests. The article in Q was posted in 2015, with interest rates (IR) at rock bottom in the wake of a 2007/8 crash whose ‘solution’ was to bail out those whose state-supported recklessness had caused it. While those masters of the universe were saved from themselves, and “moral hazard” became a household term, initial credit freezes and public ‘austerity’ were prescribed for the rest of us. (In Britain we had savage cuts to NHS etc – actually to boost FIRE sectors – while hundreds of thousands of 20 and 30 somethings were frozen out of the housing market not by high IRs but drastically raised thresholds for securing a mortgage. That’s why rents became so cripplingly high even before the recent IR hikes. Rentiers, including private landlords, had a captive market.)

The more structural answer is that historically high IRs were for a long period sustainable. Absurdly, Business Insider harks back to the 18th century, with late mercantile and early industrial capitalism booming, and the masses not directly affected since credit barely featured in their lives. For mercantile capital, high IRs were easily accommodated via its super profits from tea, silk, slavery etc. For industrial capital the story is more complex. Classical economists like Smith and Ricardo did rail against “unproductive capital”. (A banker himself, Ricardo meant that toxic mix – agrarian landlords, rotten boroughs and stacked House of Lords – which kept the morally and economically indefensible Corn Laws in place but as Michael Hudson showed in his last book but one, high interest rates were beginning to threaten Britain’s status as workshop of the world in the face of more dirigiste rivals like Germany and the USA.)

Fast forward. By the second half of the 20th century, Western capitalism was exporting manufacturing to the cheaper labour pools and more ‘business friendly’ regimes of the global south, as the empire hub morphed into consumer and credit-driven societies. For decades many but not all labour-sellers in the service dominated West felt rich. Now the party is over – one canary in the coal mine being the way a GDP-mesmerised West underestimated Russia. A GDP the size of California’s – McCain’s “gas station with nukes” – fooled US groomed technocrats/compradors into badly misreading Russia’s capacity to fight for her survival.

Technocrat compradors like der Leyen and Lagarde, and politician compradors like Blair, Cameron and Macron, were blinded by booming finance, insurance and real estate (FIRE) sectors into thinking GDP a useful indicator of economic health. It’s a devastatingly misleading one. In other posts I’ve touched on this intoxicating error.

But back to interest rates. Things were already bad in the 80s, when Mrs Thatcher, having promised a “property owning democracy”, used high IRs to curb inflation. As with Sunak and Hunt, these were (initially successful) attempts to make workers pay for capital’s profitability crises. But unlike now, those 80s assaults by the dominant wing of British capitalism – i.e. finance capital – were also on an industrial wing of capital which barely exists today. You and I are old enough to remember Terrence Beckett, leader of the CBI, promising Mrs Thatcher a “bare knuckle fight” over the hits being taken by manufacturing on the altar of high IRs. That threat was hollow then and there’s no one around even to make it now. (If memory serves, the CBI closed shop for good fairly recently.)

There’s much more I want to say. I feel I’m trying already to say too much in too short a space – a recurring fault of mine – and sense a dedicated post brewing. But in short the obvious answer to your question is the right one. These IR hikes bring fear and misery to millions. They co-exist with high energy and food prices, with burgeoning job insecurity and, as indicated, with the hyper-financialised state of UK capitalism. The rentier classes are doing very nicely but with China rising they too are on borrowed time. And the less clueless of them know it.

That’s why we’re staring into the abyss not only of catastrophic climate change, but also of Armageddon.

PS – one further point about the Business Insider piece. It also harks back to data from ancient civilisations. This is the subject of Michael Hudson’s latest book. His central thesis is that prior to the ascendance of Greece then Rome, the arrival of a powerful new king was marked by wholesale debt forgiveness. This, he argues, prevented a stranglehold, exerted by creditor oligarchies, of the kind Greece and Rome oversaw once their leaders abandoned debt forgiveness. The analogy he makes is the obvious one. Our liberal media berate the authoritarianism of Putin and Xi, but they – the CCP in particular – may represent humanity’s only hope in the face of the criminal insanity of the financial oligarchies which truly rule the West.

Hudson also explicitly makes the case that the model which destroyed the Roman and Greek Civilisations is one which has been inherited by Western Culture thanks to the pseudo Christianity of Constantine and Augustine keeping it alive.

As a model it can only function for any period of time so long as the Center (in today’s parlance Borrell’s “Garden”) is propped up by a constant and increasing tribute from the empire/periphery (Borrell’s “Jungle”).

In the rapidly emerging BRICS model that is no longer possible. When the Roman iteration of the model collapsed there was no internal capacity available to either change course or deal with the reality. Indeed, Hudson charts the best part of a millennium from the time the State in the form of the Kings were overthrown by the Oligarchy of attempts to reform the system from within which includes at least three secession’s by the plebs along with numerous initiatives to write off the unsustainable debt burden and instigate land reform.

All of which failed resulting in lethal consequences for those attempting reform as the Oligarch elite and its Establishment doubled down to eventual destruction under its own hubris rather than concede a single iota of power.

Sounds familiar.

Good points all. Glad you brought up the BRICS economies. (Other coal mine canaries include Saudi refusal to increase oil production just so Biden can weaken Russia and fight a losing battle to keep a home electorate – now going cold turkey on low energy prices – sweet.)

Though the endgame will be long and bloody, and humanity may not survive it in any acceptable form, the jig is is up for US imperialism. As profits suffer, it will do what it always does – seek to make those least responsible, at home or abroad, pay the price. But it will also seek to defend dollar hegemony in the face of BRICS and other challenges we can’t as yet identify. All the while the global south watches with bated breath.

Well, I did ask!

And I’m grateful you did, though my reply is a work in progress. Watch this space …

Good stuff Phil. A dedicated post is indeed in order!

Like Jarvis Cocker in Common People, I’ll see what I can do …