Over the decades since Reagan and Thatcher, Western economies have come to be dominated by finance, insurance and real estate (FIRE) sectors which, though highly profitable, create little new value. Rather these sectors, misleadingly counted as adding to GDP, recycle value for the most part created in the global south to which manufacturing has largely been outsourced. 1 2

From this truth, others follow:

- In the West it is finance rather than industrial capital which calls the shots. Indeed, it has captured government to the extent of it being now impossible, as Chris Hedges recently said of the USA, to “vote against Goldman Sachs” whichever party is in office. 3 4 5

- Reliance on value extracted overseas informs that Faustian Pact whereby repressively ‘business friendly’ comprador regimes, in the context of a race-to-the-bottom bidding war between ‘developing’ nations, jostle for inward investment. As I put it in 2017:

Nations early to industrialise – the ‘little tigers’ of the Pacific Rim – saw rising living standards on the back of economic liberalisation and political repression. But as other economies shift to manufacturing, the benefits diminish. The IMF’s own data rebut its claims of a virtuous circle of industrialisation and enrichment. Rather, the balance of supply and demand tilts ever more decisively, with each new entry to the ‘value chain’ by a ‘developing’ nation, to favour northern capital while the south competes in a hunger game, its winners those most able to drive down wages, and trash safety and environmental standards. We condemn Bangladesh’s sweatshop owners, polluters, slum landlords and corrupt politicians but it is the north’s elites, aided by IMF and World Bank conditionality, who set the terms under which they operate. And wealthy as the local exploiters may be, theirs is the lesser share of the surplus value appropriated. 6 Most of it flows – as shown by $720 of ‘value added’ to an iPhone made in China for $80 – unwaveringly northward.

- As globalised capital-labour relations shift value creation southwards, exploitation in the north takes the form of rising indebtedness by the many to the few in rents, mortgages, 7 student loans, regressive taxation, and insurance. 8

(That last sheds light on mounting pressure to privatise European healthcare in line with an inefficient but – for the 0.1% – lucrative US model. Most of the pressure is covert, as in cuts to Britain’s NHS in the name of an ‘austerity’ missold, to an electorate of induced economic illiteracy, through homely but specious analogies with household budgeting. In the immiseration which ensues, injections of private cash – up front and headlined, while the small print houses eyewatering repayment terms – are hailed as lifelines. Yes, this is a story writ large in the privatising of council services, rail transport and even prisons – but fat pickings for insurers, akin to the boost to mortgage lenders from Mrs Thatcher’s council house sales) make healthcare a special case.)

All of which has everything to do with Professor Hudson’s, The Destiny of Civilisation: Finance Capitalism, Industrial Capitalism or Socialism. Published in May this year – see Part 1 and Part 2 of Why read Michael Hudson? – at its heart is a distinction, between ‘earned’ and ‘unearned’ income, drawn by classical political economic theory at the dawn of industrial capitalism.

Using the distinction to shed light on a hyper-financialised West, Hudson looks to economies as far back as Egypt in the 7th century BCE, but more extensively to early 19th century Britain: then in more or less peaceful transition from agrarian economy to workshop of the world. Let’s take a closer look.

*

The 1846 repeal of the Corn Laws, in place since Bonaparte’s 1815 defeat at Waterloo, 9 was a victory for the Anti Corn Law League. Like Chartism, this had been a cross-class alliance of mill owner and factory hand whose most prominent advocates may have been radicals like Richard Cobden and Henry ‘Orator’ Hunt, but whose practical as distinct from moral arguments derived from classical political economy, in particular the work of David Ricardo.

Ricardo’s opposition to the Corn Laws drew on his theory of rent and value, which distinguished ‘earned income’ like wages and industrial profits – “rewards for risk” – from ‘unearned income’. The latter derived from monopoly ownership of a finite resource; viz, arable land in the hands of an aristocracy able to block inconvenient Commons legislation via a stacked House of Lords.

Ricardo’s focus was less on the misery caused (aggravating the slump following the Napoleonic Wars) by Corn Laws which set a floor but not a ceiling for grain prices. His gripe was that their protectionist tariffs, imposed by and for a landed oligarchy to prop up cereal prices in the face of cheaper imports from the new world, raised the cost of bread, hence of wage labour, to make Britain’s manufacturing exports less competitive. A rentier elite was draining the wealth of the nation and thereby threatening the future of industrial capitalism. 10

Repealing the Corn Laws both removed that threat and symbolised the completion of Britain’s bourgeois revolution. Now free to apply a protectionism more legitimate 11 – through tariffs on manufactured imports, and laws to inhibit manufacturing in the colonies from Bengal to Cork – successive governments of Liberal or Tory stripe committed to advancing British industry.

Protectionism and colonial diktat were not the only methods. Another was the state funding of infrastructure (roads, rail, ports) and education: burdens that must otherwise fall upon private capital, raising production costs. And as the growing complexity of industrialisation demanded a better trained and more experienced workforce, longevity became an issue. Workers dying in their thirties had not much mattered in the early days – provided they bred copiously first – but now the expenses of training argued for taking better care of them. Cue for Factory Acts, Food Adulteration Acts, public sanitation projects and curbs on child labour from the 1840s onwards.

(I don’t doubt that Lord Shaftesbury was genuinely horrified by children in coal mines; Charles Dickens by the street urchins he immortalised in Oliver Twist. Nor that such widely aired moral outrage expedited parliamentary action. But insofar as it marched in step with more material drivers of change, it pushed at doors already opening. 12 Humanism is blind to such realities, inclining us to a rose-tinted reading of modern history as the onwards and upwards march of Enlightenment values. Does this matter? Yes. It leaves us wrongfooted by the reversal of gains made under one set of material circumstances – which under capitalism equate to the needs, some more direct and obvious than others, of profit .)

*

The parallels between the dominance today of the West’s FIRE sectors, and that of the landed gentry in early 19th century Britain, are teased out by Mr Hudson:

- In both cases monopoly control of a resource essential to wealth creation lies with a tiny elite.

- In both cases the control is unearned. Ownership of most of Britain, conferred by dead kings on dead aristocrats, was and still is inherited while today’s oligarchs – think Bezos, Gates, Musk, Soros – tend to be born into well off, well connected families. More to the point though, money begets money: each new billion coming easier than the one before. (Yes, speculation is rife. Not for nothing was the term, ‘casino capitalism’, coined. For the major players though, the risks are minimised in a number of ways. One is the existence of entry barriers. 13 Another (point 4) is disproportionate influence over the rules while the cognoscenti avoid – by skill or sheer Bill, Hillary and Nancy style untouchability – falling foul of the law on such as insider trading. 14 )

- In both cases profits accrue to the monopolists through the renting out of the resource – land or liquidity – they control.

- In both cases wealth confers political power. Just as an unelected House of Lords could block (as Britain’s monarch still can) laws threatening its members’ interests, so is it now impossible, as noted in footnote 5, to “vote against Goldman Sachs”.

- In both cases the consequences are not only unjust. They are also deeply dysfunctional.

But where is Professor Hudson going with all of this? Two answers, closely related. One is the truth that capitalism’s victory over feudal privilege, symbolised by Corn Law Repeal, failed to make good on a promise understood not just by Marx but by contemporaneous thinkers closer to the mainstream. Said promise being that capitalism’s profit-driven socialising tendencies as touched on above must lead – by evolution, or expedited by revolution – to socialism. Instead, capitalism took another road – via Bretton Woods 1944, the 1971 decoupling of dollar from gold (swiftly followed by the arrival of the petrodollar) and 80s ‘Reaganomics’ – to the newer forms of unearned wealth introduced above and elaborated in my footnotes.

The second answer is to set out his grounds for cautious optimism re China’s rise as economic superpower: provided it does not lose control of its capitalist sectors; banking in particular. I share that cautious optimism, albeit with a further caveat. Will a US-led West whose rentier classes have outsourced industry, and now depend on the very exploitation Eurasian and BRIC ascendance threaten, peacefully accept a bipolar world? All the signs, in Taiwan as in Ukraine, suggest otherwise to those who, seeking the causes of such nightmarish potential, look beyond the lies, half-truths of omission and outright drivel of our systemically corrupt media.

Not that Michael Hudson is unaware of the dangers here. On the contrary his essays – on why tensions of the thermonuclear sort in Russia’s borderlands, and South China Sea, can only be understood in the context of a rattled and hence desperate Western hegemon – have hugely aided the evolution of my own thinking. But this aspect plays second fiddle in The Destiny of Civilisation.

(As, indeed, does Western imperialism’s extraction of value from the global south. Here too it is not that he is unaware of its fundamental nature. Far from it, as other of his output makes clear. But this book is on the one hand about the forms and corrosive effects of the West’s hollowing out of industry, debt-oriented financialisation and the consequent failure of capitalism’s initial promise of rising prosperity for all through socialised wealth creation. On the other, it is about whether China, by avoiding that hyper-financialisation and its capture of government, can make good on that promise.)

Be that as it may, the road being laid down by Eurasia rising, though its attendant perils terrify the not entirely somnolent, is the only one delivering a modicum of hope for humanity. 15 The West’s hyper-financialised and empire-addicted ruling classes – their capture of government no less complete for being half hidden by a thinning veil of democracy – have no solution to the greatest threats humankind faces. Rather, they are the causes of those threats. Michael Hudson spells out these things with a sparkling lucidity born of a lifetime of highly relevant experience, his erudition lightly worn. For these reasons, and for its note of stern optimism, The Destiny of Civilisation: Finance Capitalism, Industrial Capitalism or Socialism brings a breath of fresh air to questions too long silenced by mendacity, else suffocated by ultra-leftist dogma and the End of Thinking.

* * *

- ‘Value’ in the sense used here is not to be confused with ‘value chain’ theory, whose rise to economic orthodoxy came at just the right time to legitimate huge mark ups on a shirt made in Bangladesh, an iPhone in China. In attributing vastly more ‘value’ to packaging, sales and marketing of goods in the West than to their manufacture overseas, value chain theory conflates value as utility, and value as metric of exchange. In this way exploitation of the global south is rationalised as the addition of oodles of usefulness to shirt and cell phone, but the value I speak of ‘resides’ in commodities in quantities determined not by subjective usefulness but by the labour objectively needed to produce them. Since human labour uniquely has the capacity to create value greater than its own – see footnote 6 – profits are enabled by purchasing labour power at its value while selling the goods it produces at theirs. The difference is surplus value: source of all profits, much as the sun is the source of all energy; regardless of the forms either may subsequently assume.

- To classical economists like Smith and Ricardo, the facts of human labour as the basis of exchange value – and in Ricardo’s case, of capital as “stored labour” – were self-evident and non-controversial. But as capitalism grew more confident – and labour’s voice more strident – and with no other objective basis for value in sight, the case for a shift from any objectively derived value grew more pressing. Economic orthodoxy since the mid 19th century has looked instead to subjectivism in the form of a ‘marginal utility’ theory which invokes the obvious if banal truth that the usefulness of bread to a hungry person falls with each successive loaf. But applying marginalism to the super rich – as Obama’s QE program implicitly did, thereby not only rewarding their greed and further boosting inequality but failing to put its trillions where they could most boost spending – ignores truths well known to the dramatists of ancient Greece: wealth begets power, and power is addictive. (While there are more scientific ways to refute marginalism – such as that, in tandem with the law of supply and demand, it explains the movement of prices but not price itself – this one has the merit of being intuitive without being misleading. You and I have no choice but to spend any windfall in ways that boost the real economy. Oligarchs, by contrast, will hoard, speculate, buy more real estate or acquire another Picasso.)

- Finance capital’s capture of government takes many forms but let me single out just two for special mention. One is the lobbying of government by corporate interests with deep pockets; a negation of democracy, and adequate answer to those who ridicule the very idea of a ruling class. The other is a fast revolving door between government office, and plum jobs or sinecures in banking, telecomms, energy and other of the West’s privately owned FIRE sectors.

- Energy as a FIRE sector is discussed in footnote 8. And while Raytheon, Lockheed-Martin etc are not FIRE companies themselves, we cannot ignore the links between banking and armaments on the one hand; on the other, between government and a military industrial complex at its most powerful in the USA but thriving in Britain, France, Germany, Norway and other junior partners. Their Orwellianly named ‘defence’ sectors not only underwrite exploitation of the global south via wars – actual or threatened, military or economic – in the name of high ideals but having an uncanny way of taking out obstacles to dollar rule. They also effect wealth transfers – some $1tn a year in the USA – from the many to the few within the empire heartlands.

- Still on the subject of captured government, of all the ways of showing how easily class rule may coexist with the trappings of democracy, I find this the simplest: (a) democracy implies consent; (b) consent is meaningless if uninformed; (c) informed consent requires independent media; (d) that last we do not have when, as Chomsky reminds us,“media are large corporations selling privileged audiences to other corporations”. In a nutshell, the illusion of independent media supports the greater one of democracy. (Corruption by ad-dependency – and, in the Guardian’s case, the patronage of rich sponsors – is before we even get to the Rupert Murdochs of this world, to whom politicians pay homage and pledge ‘business friendly’ governance. And it’s before we get to the truth that in the USA especially, where huge war chests are essential, running for office is a non-starter without the backing of big money. Which is to say, the FIRE sectors.)

- Surplus value means here what it meant when Marx – after the Ricardian theorist, Willam Thompson – used the term: value over and above that needed to keep workers – in 21st century East Asian sweatshop as in 19th century Lancashire cotton mill – alive and raising the next generation of value creators.

- Frenetic mortgage lending not only led junk economics into the subprime-triggered crash of 2007/8. Spiralling prices form a vicious cycle to reveal the Ponzi nature of the housing bubble. As long as they keep soaring, new buyers will – in bidding wars which push them up further – take on lifetimes of debt. So too will buy-to-let speculators whose tenants, unable to raise deposits more exacting since the crash, pay more in rent than they would have in mortage repayments. But Michael Hudson, who cut his teeth as an economist in the field of debt, shows mortgage outgoings in total – including those paid by landlords – exceeding rents from property lets. The latter are eclipsed by the sums accruing to the mortgage, debt insurance and debt trading sectors.

- I do not say the hyper-financialisation of Western economies is confined to mortgages, rent, student debt, legalised tax avoidance, and insurance. The trade in debts as assets (like the ‘collateralised debt obligations’ which kicked off the crash) … the sums lent and borrowed to finance corporate raids and share buyback … short-selling, ‘put’ and ‘call’ speculation … these features of today’s casino capitalism create no new value – few of the sums changing hands will finance industry – but do create profits from the renting out of money. As such they are part of the picture. When Obama told Wall Street fat cats he’d saved them from the “pitchforks”, via a QE program as economically dysfunctional as it was morally disgraceful, he meant every word. A UK energy sector privatised by Mrs Thatcher owes a similar debt of gratitude to the incoming prime minister, Liz Truss, for her equally dysfunctional and disgraceful response to soaring fuel bills. And since we’re speaking of extractive industries, we should keep in mind that most value in that quarter is created ‘downstream’ of oil wells, mines, quarries and fracking sites; all of them forms of real estate. ‘Upstream’, the profits pour in as unearned income from a monopolised natural resource which may be inherited (the British royal family and related oligarchies), looted (Russian gas barons, their fortunes made overnight amid IMF-prescribed disaster capitalism under Yeltsin) or the recycling of other unearned incomes (Bill Gates, on a ten year land buying spree, his initial pile made by renting out a computer operating system of contentious provenance). Nor should we forget the Anglo-American reappropriation of Iran’s oil in 1953. But my narrower point here is that until the Ponzi schemes collapse and non-inflationary QE is no longer an option thanks to the demise of the dollar as the world’s reserve currency – a demise hastened by the global south duly noting, inter alia, Washington’s lawless asset seizures in Iraq and Syria, and its lawless freezing of Afghan, Russian and Venezuelan deposits in its own vaults or those of vassal states like the UK – the West’s 1% will continue not only to plunder the planet, but to grow ever richer on the debt-driven impoverishment of its own 99%.

- The name most associated with Bonaparte’s defeat is that of the arch reactionary Duke of Wellington. Thirty-one years later, now Leader of the House of Lords, Wellington had this to say of PM Sir Robert Peel striking out the Corn Laws he’d previously backed to the hilt: “Ireland’s rotten potatoes have done it all – put Peel in his damned fright.” The Iron Duke was connecting – not entirely accurately – Corn Law repeal to the Great Famine which had reduced, by a quarter, potato dependent Ireland’s population; one million to death by starvation, another to New World exodus. It has also to be said that recent events in France had a way of persuading the more prudent wings of British aristocracy of the case for reform; a task made easier by its more cash-strapped elements having held pegs to powdered but pragmatic noses and married their daughters to self made men, inclining them to look more kindly on the needs of industry than they might otherwise have.

- Ricardo’s fears were not confined to the corrosive powers of a feudal oligarchy. Though he and Thomas Malthus clashed, he shared the latter’s pessimism. And while his gloomy predictions for capitalism’s future helped keep him an honest inquirer, focusing as they did on the finite capacity of the soil to support a burgeoning proletariat, they also caused Marx to quip that the man had “fled from political economy to organic chemistry”.

- I use legitimacy in a historic rather than humanist sense. By protecting the beneficiaries – few in number but wielding great power – of a dying political-economic order which now stood in the way of human progress, the Corn Laws were a Bad Thing. But since industrial protectionism a few decades later would aid – via the self interest of Britain’s new ruling class – the rise of a more efficient order, it was a Good Thing.

- On the importance of a materialist understanding of history, another example is the anti-slavery movement on both sides of the Atlantic. Here too no one can doubt the fiercely moral imperative driving a Wilberforce or Beecher Stowe, nor the skills and energy which gave it force and purpose. But their voices too were in step with developments less high-minded. In Beecher Stowe’s case the mills and factories of the northern states, in direct competition with Germany and Britain, had an insatiable need for wage-labour sources denied to them by slavery in the south. As for Wilberforce’s success, only recently has it become known – not widely enough! – that compensation to British slave owners only ceased in 2015. To be pedantically clear, I speak of a 182 year stream of payments, from British taxpayers to the descendants of slavers, for ‘human property’ lost to Abolition.

- Entry barriers form one of capitalism’s many internal contradictions. Competition drives down prices; lower prices demand economies of scale. The latter lead via buyout and takeover to monopolies, which stifle competition. Brits with eyes in their heads can see the visible tip of this iceberg by walking down any high street and counting the number of independent retailers and pubs: their rarity the exception that proves the rule. Do the lower prices of Wilco and Wetherspoons benefit the consumer who in all probability is also a worker (or a dependent of one)? Not really. But for the why of that, a labour theory of value – anathema to post classical economics – is needed.

- Risk is also minimised by hedging investment exposure through funds necessarily large. Since these also benefit pensioners and municipal authorities, a specious argument –“we are all rentiers now!” – is often advanced. It’s not always clear whether this is offered in good faith but, be it disingenuous or merely obtuse, it tramples over that vital distinction between those whose incomes derive primarily or entirely from personal ownership of wealth as capital, and those who must sell their labour power (or prior to retirement did sell it, or alternatively are unable to sell it and must scrape by on benefits) in markets which cannot but prioritise profits over people. Clarity on such truths strips ownership of a few shares, or receipt of a state pension, of their obfuscatory power.

- “… the road being laid down by Eurasia rising … is the only one offering a modicum of hope for humanity …”

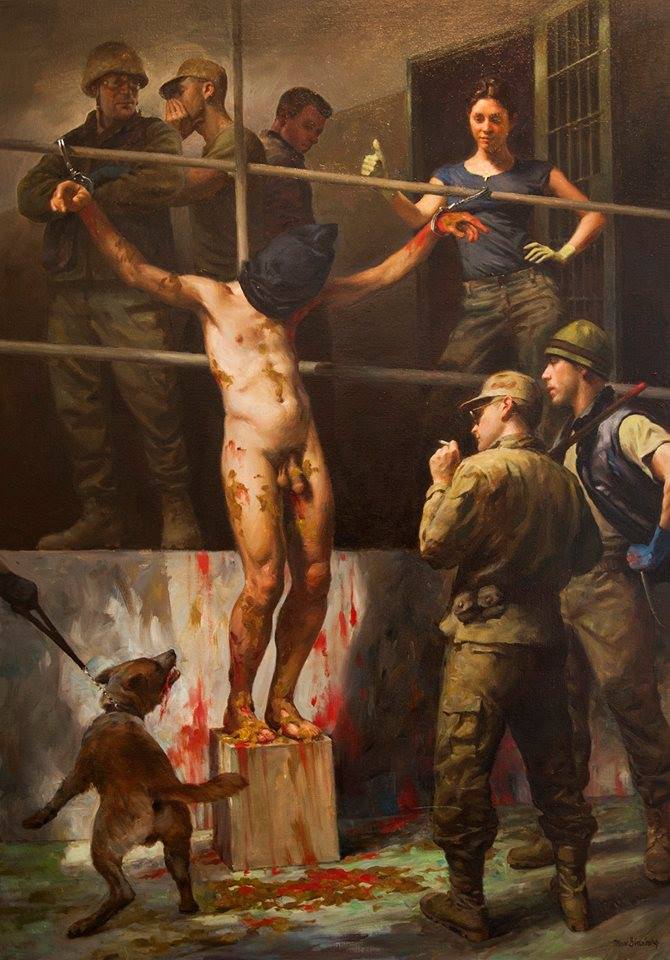

See my open letter of a year ago. I’ve little time for objections to China as ‘authoritarian’ while those raising them childishly take the West’s democracy at face value and remain silent, or smugly hurl accusations of ‘whataboutery‘, in the face of the millions slain and displaced, starvation sanctions, extraordinary renditions and enhanced interrogations – all in the name of liberal values but in the interests of Wall and Threadneedle Streets.

As for Leftist critics, in a footnote to that open letter I said this: “China’s capitalists (a) have been an important component in a miracle that’s lifted hundreds of millions from what the World Bank calls extreme poverty, (b) are subordinate to state policy – when in the West it’s the other way round – and (c) exist precisely because the failure of the West’s Left to make its own revolutions obliged China to adapt to global conditions of entrenched neoliberalism.”

I’ll be sure to let you know the moment I get a solid rebuttal of these points.