Tax specialist and modern monetary theorist Richard Murphy is no Trotskyist. But as I said in a recent post he has a way of formulating demands which (a) meet the needs of the hour and (b) are not on the face of it revolutionary yet (c) cannot be conceded by the ruling few.

Such demands can be seen, even by people in the grip of serious misapprehensions as to why things are the way they are, to be right and necessary. But other than as limited and short term concessions made with its back to the wall, 1 no capitalist state can allow them.

And such demands are hallmarks of Leon Trotsky’s thinking. Given the Left’s interwar defeats in Italy and Germany, it had dawned on socialists that the proletariats of the advanced capitalist economies would not be seizing state power any time soon. And that, consequently, the gains of 1917 stood in mortal peril.

(It had been axiomatic that the seizure of state power and, more impressive, victory in the ‘civil war’ by Trotsky’s Red Army would afford a holding operation only. Having gained control of one of the most backward economies in Europe, Russia’s leading Bolshevik strategists, Lenin included, had predicated long term survival on revolution in Britain or Germany. The triumphs of Mussolini and Hitler necessitated a rethink. For Stalin that led to the oxymoron of “Socialism in One Country”. 2 For Trotsky, now the prophet in exile, a transitional programme was needed to bridge the gap between objective need and the masses’ current state of awareness.)

I repeat. Professor Murphy is no Trotskyist. Nevertheless yesterday, on the 75th anniversary of Hiroshima, he was at it again:

It’s time gas and electricity supplies were nationalised in the interests of all consumers

As the Guardian has reported this morning:

Millions of homes will be forced to pay some of the highest energy bills for the past decade after the industry regulator gave suppliers the green light to raise their prices by up to £153 a year.

Households across Great Britain that use a default energy tariff to buy their gas and electricity can expect a sharp increase in their bills from October this year after the regulator lifted its energy price cap for the winter.

This is profoundly worrying.

Firstly, the reason for the price increases is supposedly because of market pressures. Actually, as massive profit increases at BP, Shell and other companies shows, that is nothing more than profit-taking.

Second, this is apparently intended to keep small market suppliers afloat – because otherwise they would go bust and the supposed ‘market’ in domestic energy supply would fail.

Third, the impact will, of course, be deeply regressive: fuel poverty is a fact for those on low incomes.

Fourth, this will inevitably link to flu deaths: they are largely caused by fuel poverty.

Fifth, note this is happening as Universal Credit is cut by £20 a week.

Could you make this up? Only if you are a believer that markets are for the benefits of the companies in them and are not for the benefit of consumers could you make any such scenario up.

What were the right reactions to price increases?

First, if companies were going to fail as a result, they should have been allowed to do so. That’s what happens in markets.

Second, if there is no domestic energy market (and there is not: it’s an abusive charade, exploiting the least well off most) then the pretence should be dropped.

Third, the companies in that market should be nationalised. That’s what should happen for utilities where come what may, whoever you buy from, there’s only one wire and one pipe into your house and no real choice at all.

Fourth, a nationalised energy supplier should supply a clear, simple, tariff that is lowest price to all. The current exploitation of the elderly, those without internet and who stay with a supplier should end for good.

Fifth, that nationalised company should be run on a not for profit, after allowing for funding reinvestment basis.

Sixth, if there are forced price changes because of market moves, that company should be required to work with other government agencies to provide credit to those least well off to protect them from sudden price changes.

Or, seventh, pensioners and those on universal credit should get a fuel adjustment to their payments to allow for such changes instead.

We have a state to protect us. That protection includes the expectation that the state will prevent poverty. The state we have is not doing that. And it is not good enough. It’s protecting companies instead.

We need a state that gets priorities right. It’s really not hard to do. I have set out the mechanism. Now, why can’t we have Opposition parties agree on such policies to ensure that they can deliver the protection that this government will not provide?

Other than the naivity (or Trotskyist bluff-calling?) I have highlighted, I’m with you all the way Prof. 3

*

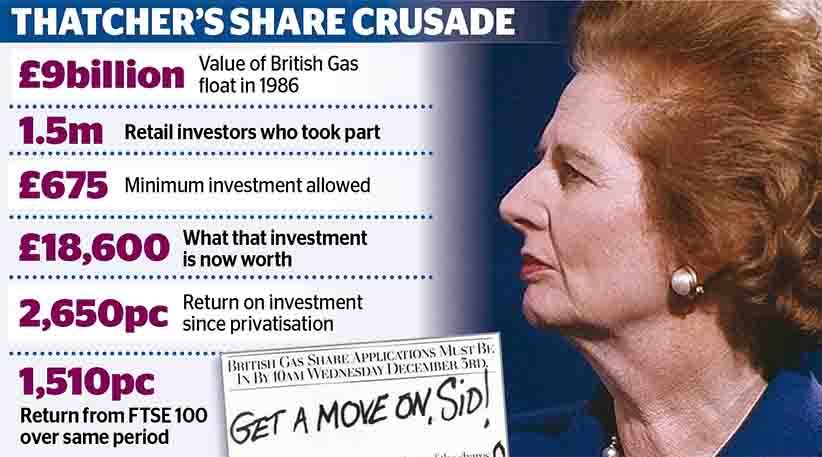

- The great nationalisations of Atlee’s single term 1945 stint were not quite the victories Labour myth has it. Coal, steel and rail exemplify the inherent contradictions in ‘pure’ market discipline. All three were vital to capital; all making a loss. Saddling taxpayers with them, while being handsomely compensated, was just the ticket. After all, the moment state cash injections made them an enticing prospect once more, those same taxpayers – and/or their baby-boomer progeny – would be easily convinced by our ‘independent media‘ that privatisation is, well, just the ticket. But don’t tell Sid.

- Socialism in One Country is indeed an oxymoron but that doesn’t make Stalin wrong. What were his choices? In recent years my sympathies with Trotskyism have cooled as sects claiming his mantle – and that of ‘permanent revolution‘ – got it hopelessly wrong in the middle east and continue to look childishly at Beijing. More recent than this disenchantment, yet related, is my willingness to welcome the rise of China not only as a check to US Exceptionalism, but in its own right.

- A forensic but readable account of what happened subsequent to six of the biggest sell-offs in the UK is given in James Meek’s lucid and closely empirical Private Island. But as I will keep saying, I do wish those who rightly recoil at the privatisations of bus operators and utilities, council services and prisons – and the creeping privatisation of higher education and NHS – would let in the bigger picture. The same movement, to privatise the world and monetise its every aspect, also drove the dismantling of the Soviet Union and demolition job on Ba’athist Iraq.

Gas, as with the other utilities created by public money over generations, electricity and telecoms (initially nationalised in 1912 as a result of too many competing systems to be both efficient and effective) have been reconstructed (as well as stolen) on the basis of artificial competition.

Ofcom (and its predecessor Oftel) along with its counterparts in the energy industry operate on the basis of an article of faith enshrined in Parliamentary legislation (and thus in law with no deviation possible) that the only way to achieve a desired outcome is via competition rather than co-operation.

I recall making a submission to Oftel making this point a few years after the turn of the century in its Telecom review. One example of which concerned the fallacy of this starting point in relation to just one aspect of the proposals which subsequently became enshrined in both law and general practice, directory enquiries.

At that time it was just not possible to improve for the customer a service in which you rang a single easily remembered number – 191 – to obtain a telephone number at zero cost to what at least some of us insisted on calling subscribers, rather than customers. Oftel’s competitive model not only monetised that aspect to the detriment of the “customer” – so much for consumer sovereignty – it made it more difficult by introducing a form of artificial competition where the subscriber (sub) had to remember too many numbers whilst also paying for something which had previously been free of charge.

Again, the fixation with the evidence free Thatcherite doctrine of competition as the only viable route to achieving an objective threw up some ridiculous outcomes which remain with us today. Another concern I raised in that submission to Oftel was how would it be possible to avoid certain practical difficulties of allowing this artificial pseudo- competition into the network?

By this time I was in an office function after twenty years of jointing cables. If umpteen companies have access to the same network how are you going to maintain quality standards in the network infrastructure of cables (underground and overhead); street cabinets, joint boxes, manholes, poles (at least four million) and exchanges if anyone can get access? If a cable was going faulty with pairs allocated to half a dozen or umpteen different competing companies who gets access first? It would be like the wild west which led to the initial 1912 nationalisation.

The ‘solution’ was the creation of ‘Openreach.’ Seperating off part of BT to do all the expensive donkey work of maintaining and upgrading the network infrastructure assets for all the other companies.

This created its own ridiculous and bureaucratic nightmare. We had already been down this route in the eighties with Mercury. A company created to sustain the myth of competition being the route by creating an artificial competition. It worked thus:

Mercury connected to the newly privatised BT network at the exchanges down the main trunk network. To simplify (because this also operated the same way for the more revenue lucrative data lines) Someone on their figure of eight trunk loop (really BT’s paid for over generations by public investment) would make a call to another part of the country. The small amount of revenue from their location to the exchange and vice versa at the other end of the call (the local call) would go to BT. The larger amount of revenue from the trunk network Mercury’s kit was connected to would go to Mercury.

BT were also forbidden to provide enhanced entertainment services down their own network (known as the asymmetry rule), whilst cable companies targeting mainly working class council estates had no such restriction even if connecting to the formally public network provided by previous public investment.

Bearing in mind (and this is likely to be the same for other utilities) what is known in the industry as the 80/20 rule. That is 80% of the revenue is generated by 20% of subscribers/customers. And vice versa. When telecoms was a public utility there existed cross subsidisation. Otherwise many communities outside of urbun concentrations would never get service. The ending of which (cross subsidisation) saw many of those communities having to wait a considerable amount of time for proper broadband connections (but that’s another story for later).

The same thing happened on a larger scale with the creation of Openreach. The first problem with this pseudo artificial competition is the cost. Oftel, and it’s offspring Ofcom, regulate that other companies accessing the network which Openreach maintains pay a set fee for accessing the network.

The problem here is that those companies don’t have to bear the true costs of maintaining that network. The personnel staff costs (jointers, cablers, faultsmen, pole erection, back office staff), vehicles, consumables, equipment tools etc etc.* Imagine being forced to let someone live in your house for a peppercorn rent whilst you foot the bills for the mortgage/rent, Council tax, energy, insurance, repairs etc. Or Tesco being forced to allow Aldi, Lidle, Sainsbury’s etc to set up their own check outs at a low rent to get a slice of the revenue without paying the full cost of transporting the goods etc to the Tesco supermarket.

* Resulting in many of these functions sub-contracted out on the Carillon model as well as closures of facilities; transfers of in house workers to other companies; and a reduction in every metric of terms and conditions from relative pay through to pensions, attendance patterns, sick leave etc.

But it gets worse. Firstly the bureaucracy required for this fiction to exist of total separation in the name of what is in reality artificial competition.

Before Openreach and opening up the local loop to this faith based doctrine if you had a fault on your BT line you made contact with a single point of contact. This found its way down the chain to the faultsman who tested the line. If it was underground (UG) it was passed to the UG Control. If elsewhere and accessible (subs premises, pole, etc) the faultsman fixed it. Simples.

After Openreach and opening up of the local loop for others (talk, talk; Sky; Virgin et al) it became a more bureaucratic time consuming process which introduced time inefficiencies into the process to the detriment of the end user, the ‘customer.’. Something which is not supposed to happen with the faith based doctrine of ‘compettion’ upon which the whole edifice is built.

Most end users, having being used to calling a single point of contact, BT, found themselves being directed to call their new supplier if they had switched. The new supplier contact Openreach who then contact the local, increasingly regional, control who allocate the job to the faults engineer In cases where the fault is traced to the equipment side of the exchange (new suppliers connection) the Operach engineer in the name of ‘competition’ is forbidden to go any further. It is passed back up the chain and Openreach contact the new supplier who then passes it down their chain to their own technician who covers a larger geographical patch (there being fewer of them) to visit that exchange no matter how far away (introducing further time inefficiency into the process).

Secondly, the impact of this approach since the privatisations has resulted in a detrimental impact on internal cohesion. Internal competition between different units within the organisation based on simplistic tick in a box quantative targets has seen an increasing begger thy neighbour structure and process emerge. One in which no consideration exists for the impact of pursuing individual unit targets have on other complementary units doing the same thing or on the overall system.

Consequently, instead of the whole being more than the sum of the parts (2+2=5) the whole is increasingly less than the sum of the parts (2+2=3 or even 1) whether you are talking about telecoms, energy or water/sewage (water/sewage being particularly precarious).

The energy sector is arguably of more concern than telecom given the fact that in addition to the same problems arising from the same structures and processes described above in the telecom sector there is the added complication of the still carbon dominated energy sector being reliant on massive direct and indirect State subsidies (public money). Quite how Thatcher who championed and instigated this nonsense would justify private companies being more reliant on public subsidies than the public sector she claimed was instatutionally and irrevocably bloated.

Not to mention the geo-political dimension. Perhaps of even more concern, despite Murphy’s more rational options, is the total absence and lack of interest in an alternative approach by what passes for an opposition in Parliament. An opposition which increasingly resembles a caricature of a sect which could give Stalinism or Trotskyism a run for it’s money given its fixation with driving out anyone who disagrees with it.

I do have sympathy with Prof Murphy’s call earlier this week for an end to First Past the Post. FPTP is less grave affront to democracy than that of media whose business model debars them from speaking truth to power on anything that really matters. So PR is an aspirin for cancer but it would hasten a split between the two wings of Labour: that devoted (ostensibly at least) to ameliorating capitalism’s worst effects; and that devoted (ostensibly at least) to the oxymoron of ‘parliamentary socialism’.

Given the lamentable state of Labour now, that has to be a good thing. I guess this makes me a supporter of PR, albeit a decidedly tepid one …

On the matter of PR I sat through an interesting presentation a few weeks back – though the slides have not yet made their way down the chain.

The key points being under FPTP:

– Many voters see their votes wasted in two ways:

– 1. They Party they vote for never wins the seat under a winner take all system where the winner can take the seat with more often than not less than fifty per cent of the vote. Sometimes this can be as low as 29%. There is little point in campaigning for losing party’s in these safe seats.

Conversely

– 2. In many seats those voting for the winning Party have so many votes over the second place Party that they are effectively surplus.

– It takes considerably more votes to achieve a Labour MP under FPTP than a Conservative MP.

– Compared with States operating under PR systems those States operating under FPTP regularly:

– 1. Return right wing Governments

– 2. Are more unequal on a range of key metrics.

If I ever receive a copy of the slides I’ll post them as they are worth half an hours digestion.

In the meantime the best I can offer is this link to the Official LP publication:

https://www.makevotesmatter.org.uk/labour4pr

Yes. FPTP has to go as a first step to some kind of electoral fairness. If we ever get so far, then the next step should be Sortition, where a random sample of participants decides on each major aspect of government policies. Sounds mad, yeah? But that is the original Greek form of democracy, and to had been proved to be efficient elsewhere and at other times.

Hear, hear – especially the last sentence.