Mrs Thatcher said she could “do business with him”. Western liberals – unlike the citizens of a USSR about to be plunged into a living nightmare 1 – had the kind of love affair with him which today finds echo in a man of far smaller stature, Volodymyr Zelensky. Mikhail Gorbachev, he of the kindly, intelligent face and calmness of bearing who, for a short while after Cold War One’s final and most frightening decade, had made glasnost and perestroika household words in the West, died five days ago on August 30. He was ninety-one.

The outpourings of Western media eulogy were predictable. You’ve likely read a few, or at least caught the gist from sound bytes. On offer here though are two responses as different from one another as both are from the hagiographic revisionism of corporate media. Both appeared the following day, on August 31.

One is by Andrea Peters on the World Socialist Website, often cited more or less approvingly on these pages, though seldom without a distancing caveat on my part. In this case I distance myself even further than usual. Though Ms Peters does not follow corporate media in singing his praises, as though the views of the masses of the former USSR were of no consequence, she commits the opposite sin. Her piece demonises Mr Gorbachev in that boilerplate way WSWS, and almost all of a Trotskyist Left which once called me comrade, do so go in for.

There is little nuance, far less dialectic, in her understanding. Holding firm to the non negotiable take on Russia’s revolution as betrayed by a bureaucracy which would ultimately – at just what point is one of many bones of contention by which the splinters of the 4th International locate and fetishise their differences – go beyond parasitic exploitation of the property gains of 1917. This bureaucracy would, said Trotsky – and history would prove him right about many things – be obliged to roll back those gains and constitute itself as a fully blown ruling class on the basis of their reprivatisation.

At root of that perspective is the notion that the USSR could have made other choices – that the rise of Stalin, and a ruling caste which held sway through Kruschev and Brezhnev, Andropov and Gorbachev, could have been averted had Trotsky and his doctrine of permanent revolution won the day, circa 1920-25. Personally, and I speak as an admirer of Trotsky – not an uncritical one but an admirer all the same – I find such whatiffery far fetched. The world’s first proletarian revolution took place not in an advanced capitalist state but in one of Europe’s most backward countries. (Even the term ‘proletarian revolution’ is misleading. It was far more a palace coup led by bourgeois elements, leading to the mobilisation of the tiny working class in Moscow and St Petersburg, and of a vast but murderously divided peasantry.) None among that leadership – not Lenin, not Trotsky, Bukharin, Kamenev, Kollontai, Zetkin, Zinoviev; no, and not Stalin either – gave time of day to the idea, at once both heresy and oxymoron, that a fledgling USSR – least of all one crippled by a punitive Brest-Litovsk Treaty followed by starvation blockade, by three years of civil war and by imperialist invasion – could manage more than a holding operation, pending successful revolutions in the advanced economies of Britain, Germany and Italy.

Well that didn’t happen and, given the triumph of fascism in one of those nations – and rising fortunes of an even more nightmarish variant in another – the faction around Stalin, emerging victorious from struggles with the Party’s left and right factions, committed the Soviet Union to a course hitherto dismissed as utopian fantasy; that of “building socialism in one country”. It is an article of faith among Trotskyists, whatever else they may disagree about, that the Soviet Union, despite being exhausted and with no ally in sight, could have taken a different path.

Me, I doubt it. Nor is this simply an arcane point of ancient history. To this day, in a rare meeting of minds with Maoism, Trotskyist sects in the West, having failed to make their own revolutions, now have the nerve to admonish China for “abandoning socialism”. Their analyses of current events – from the Middle East (on which WSWS has a better record than most) to terrifying US-led warmongering in Russia’s south-west borderlands and South China Sea – lead them more often than not to the rabbit from a hat trick of damning Beijing, Moscow and Washington alike, while calling for an international workers’ revolution which is so not going to happen.

At least, not in the West. As I put it in an aside a year ago to a post on Richard Murphy, the modern monetary theorist:

I too reject revolution, though unlike Mr Murphy I am not a Quaker. Nor a pacifist in the sense of one who regards all violence as by definition wrong. I reject revolution as envisaged by Marx and modified by Lenin because, in the West at least, that ship has sailed. Seizing state power is not going to happen for two reasons. One, the industrial conditions so ably depicted by Marx and Engels no longer hold. With manufacturing exported to the global south, the proletariat has lost both its muscle and the conditions whereby its exploitation was experienced en-masse.

Two, the British and all other Western ‘democracies’ are armed to the teeth, versed in the black arts of counterinsurgency – honed on the streets of Belfast and Gaza – and above all equipped with tools of surveillance beyond the wildest dreams of the twentieth century totalitarianisms.

But we steel city scribblers are nothing if not open to persuasion by evidence and reason. Here is that assessment of Mr Gorbachev by Andrea Peters, writing four days ago on the WSWS site.

The death of Mikhail Gorbachev and the legacy of Stalinist counterrevolution

Mikhail Gorbachev, the former general secretary of the Communist Party (CP) and president of the Soviet Union, died on Tuesday at the age of 91 in a Moscow hospital. He had reportedly been suffering from kidney disease for several years.

Gorbachev, who joined the CP in 1950, was a loyal servant of the Soviet bureaucracy for three and a half decades. He was responsible for the final act of betrayal carried out by the parasites who raised themselves up above and fed off the Soviet working class: the full-scale restoration of capitalism and the dissolution of the USSR into more than a dozen states. He was a man with whom, in the words of arch-reactionary Margaret Thatcher, “one could do business.”

Gorbachev’s policy of perestroika (restructuring), implemented over the course of the 1980s and early 1990s, initiated the systematic dismantling of the system of nationalized property that emerged out of the Russian Revolution of 1917. Perestroika scrapped restrictions on foreign trade, legalized small businesses, ended subsidies for key industries, tossed out labor laws and threw the Soviet economy and society into disarray.

Enterprises suddenly forced onto a system of “self-financing” found themselves unable to secure the resources they needed to produce, pay wages or fund the social services and benefits that were the right of the working class and the backbone of their living standards. Managers of the most well-positioned factories, directed by the state to manufacture for profit, diverted goods from the state sector of the economy and sold desperately needed consumer items at whatever price the market would bear.

The reforms initiated a process of the wholesale looting of state assets. The children of the elite took advantage of special legal privileges granted to members of the communist youth organization, the Komsomol, to open businesses and sell Soviet assets and resources domestically and abroad. An entire secondary banking industry emerged, as those with access to enterprises’ financial accounts set up lending operations that profited off the crisis and social desperation.

By 1989, about 43 million people in the USSR were living on less than 75 rubles a month, well below the official poverty line of about 200 rubles. Writing in 1995, researcher John Elliot described the era as characterized by “deteriorating quality and unavailability of goods, proliferation of special distribution channels, longer and more time-consuming lines, extended rationing, higher prices … virtual stagnation in the provision of health and education, and the growth of barter, regional autarky, and local protectionism.” Officially, about 4 million were unemployed as of 1990, although specialists argue that was a vast undercount, with the real number being as high as 20 million. With masses of people shipwrecked, alcoholism, drug use and deaths of despair all exploded during the years to come.

For all of this, Gorbachev is widely and rightly hated throughout the former USSR …

For what it’s worth, I agree with much of that. As it so often is, my gripe is with the de rigeur Trotskyist ‘alternative’ which follows. Rather than repeat my arguments, let me simply offer this link to the full piece – it’s quite short – and let you be the judge.

*

On the same day as the WSWS piece, Jeffrey Sommers – Professor of Political Economy and Public Policy, and a Senior Fellow at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee’s Institute of World Affairs – wrote the kind of assessment you’re no more likely to find in Guardian or Economist than the Andrea Peters offering. Though I hadn’t come across the professor prior to this, a little digging soon uncovered that (a) he is an expert on the Baltic states and (b) a piece he co-wrote with political economist Michael Hudson – a blistering take down of the idea of Latvia as a poster boy for ‘austerity’ – appeared in the Guardian eleven years ago.

Click on the image to read the Guardian article

Which piqued my curiosity. Having read the Latvia piece, I turned to Jeffrey Sommers’ appraisal of Mr Gorbachev in CounterPunch, to find it a timely antidote to the superficiality on offer in corporate media eulogies. Neither hatchet job nor hagiography, I recommend reading in full.

How Mikhail Gorbachev Became the Most Reviled Man in Russia

Mikhail Gorbachev presented a figure of Greek tragedy proportions. Possessing good intentions and intellectual curiosity, Gorbachev nonetheless became the most reviled man in Russia, following the USSR’s demise. Yet, with Gorbachev, his worst qualities were connected to his best. Gorbachev was the wrong man at the wrong time to resolve the contradictions created by the Stalinist and then Brezhnev bureaucratic model of really-existing socialism in the Soviet Union. Increasingly hated at home, Gorbachev was beloved by world leaders in the “West” as the man who peacefully (at least by the comparative metrics of collapsing empires) unwound the USSR, even if trying to save its all-union character. Meanwhile, for China, Gorbachev delivered lessons in what not to do when reforming a sclerotic post-Stalinist system requiring economic reforms, if not transformation.

What happened when the USSR produced its first post-World War II leader untethered to Joseph Stalin (and those he appointed)? Answer: a liberalizing socialist seeking a return the origins of the USSR’s democratic anchoring in the spirit of the “Soviets.” Contra assertions of Friedrich Von Hayek that socialism represents the “road to serfdom,” the emergence of Gorbachev suggests the opposite. Terror and tyranny in the USSR arose more from war and the demands of state security services required to survive, and the paranoid politics it enabled, rather than any “inevitable” path from the socialist path taken. Once the USSR was passed the generation having gone through this trauma (and leaders linked to that generation), a communist party head emerged that sought a return to an ideology anchored in democratic socialism.

As with nearly all of the Soviet Union’s leadership, Gorbachev had provincial origins, in his case born in 1931 in Stavropol Krai just southeast of Ukraine. His maternal grandparents were ethnic Ukrainian. He rose through the party ranks with a reputation for hard work and finding solutions to vexing challenges. By 1979 he was in the USSR’s highest governing body, the Politburo, and by 1985, selected to the country’s highest post as General Secretary to lead the Soviet Union out of its economic stagnation.

Gorbachev was a serious Leninist, and not just a bureaucrat reciting historical materialist catechisms out of momentum or political expediency. Confirming what historian Stephen Kotkin asserted in his biographies of Stalin, Soviet party leaders were not party posers, but genuine believers in communism who often walked the talk. But, what many thought the USSR needed in its time of trouble was Lenin’s firm hand and not democratic socialist inspired experiments done on the fly.

Ironically, it was these aforementioned democratic characteristics, which ensured the failure of Gorbachev’s reforms. For every crisis, Gorbachev encountered, his go to inspiration was to be found in Lenin’s writings. Like Lenin, a provincial figure that transformed Russia, he was nonetheless not Lenin. Gorbachev focused on Lenin’s democratic message for the future, but not his decisiveness, if not brutal ruthlessness that allowed him to carry off the Soviet Revolution. By contrast, Russia’s current leader, Vladimir Putin, possesses the other half of Lenin’s personality: his ruthlessness, but bereft of any democratic purpose.

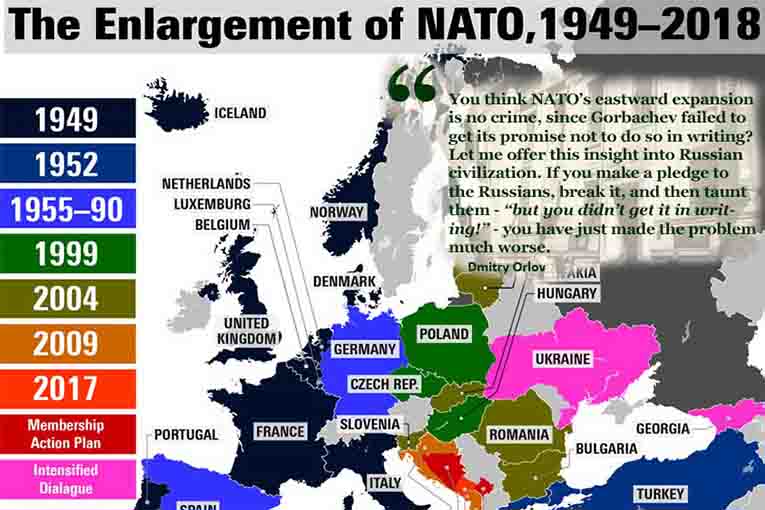

Personally I find that last – Professor Sommers’ sole reference to Mr Putin – a little premature. Given the chaos and attendant power blocs he inherited from Boris Yeltsin’s acquiescence to the shock therapy of IMF ‘market reforms’ – and to the betrayals of Gorbachev marked by wave upon wave of NATO expansion including the criminal dismemberment of Yugoslavia – it seems to me too early to say whether or not the current Russian leadership has any democratic intent. Nor does Professor Sommers offer any evidence on the point.

All the same, I repeat my recommendation. For its insights into the lessons that China, on Deng Xiaoping’s watch, drew from the collapse of the USSR – and into how that USSR had been less advantageously placed than is China today – this closely argued piece should be read in full …

* * *

- One of the best accounts I know – and I’ve read a few – of that nightmare to which the IMF, amply aided by Mr Yeltsin, subjected Russia is in Chapters 10-11 of Naomi Klein’s meticulously documented Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism.

Well, I still cling to the notion that if Lenin had not become ill and died when he did, things would have been very different. Maybe not a workers paradise, but the individual and mass killing enacted by the psychotic Stalin in pursuit of his demons would not have happened. Lenin before he died was aware that Stalin was a dangerous individual, who was unsuited to power. But by then he was unable to do anything about it, and Stalin comprehensively outmanoeuvred both Lenin and Trotsky. If Lenin had stayed healthy and lived and stayed in power longer he was certainly ruthless enough for actions which may have cost lives, but he was also aware of the injustices involved in the revolution as it stood, and would have tried to minimise those in the future.

As for Gorbachov, he may have undermined the foundations, but it was the drunken idiot Yeltsin who set fire to the house. Putin has rebuilt it again to a different design. And as for his democratic intent, I imagine he is constrained by what is possible rather than what he would like. He also shows no signs of being a socialist, but he has restored a lot of the wealth stolen by the oligarchs back to the state, and he has the very powerful example in front of him, in China, as to how a socialist society can be successful. As China and Russia will have to (and do) co-operate very closely until their idea of a new economic regime emerges, then who knows how the Russian state may change. But as they say, forecasting is very difficult, especially regarding the future.

I’m inclined to agree, Jams.

Agreed. But it strikes me as excessively idealist as well as individualist to suppose Lenin could magically have transcended – he would be the first to dismiss such a notion – the objective forces arraigned against the USSR at that point.

On the other side of the equation, in The Revolution Betrayed, Trotsky does give credit to the extraordinary leaps forward on Stalin’s watch. Of course he attributes these gains to a planned economy despite, not due to, Stalin’s brutal philistinism. (Despite too Stalin’s late 20s abolition of the soviets which, given more favourable conditions, just might have offered an alternative on the one hand to the boom-slump chaos of capitalist production; on the other to heavy handed top down planning by diktat.) That is as maybe but when Hitler shredded the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact exactly as Trotsky had foreseen, Stalin – a lucky fellow! – survived when he should have been ousted. (Indeed, some accounts show him fully expecting to be arrested and shot after Hitler’s Operation Barbarossa. One tale has it that when senior army officers came to his house, Stalin was sure he had hours at most to live. In fact, according to this account, all they wanted were the Great Leader’s orders as to what to do next!)

At the cost of 24 million slain the Soviet Union fought back and, by the time of Stalingrad, had shipped entire factories 3,000 miles east to put more planes in the air, and tanks on the ground, than either the Allied or Axis powers had imagined possible. (That’s another tribute to economic planning, though of course all wartime economies are planned: just not with the twenty year head start, going back to Lenin’s War Communism, the USSR enjoyed at the time of Nazi Germany’s attack.) Could a USSR under Lenin have done the same? Undoubtedly, and it is unlikely a leadership around him, even if it had signed that Pact (to which there were pros as well as cons for the USSR) would have been so naive as to Hitler’s intent.

But could a USSR under Lenin have done better? I rather doubt it. Again, the historical material forces in play were too vast.

I agree with what you say, but the malign influence of Stalin should not be minimised. He really was some kind of paranoid psychopath, and many lives were lost and much damage was done to the economy because of this. Lenin, being a completely sane and realistic individual, would not have left such a trail of unnecessary destruction behind him. However, it seems even forecasting of the past is difficult.

Well I’m not going to defend Stalin! Since I did cite the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, it’s worth throwing in another anecdote. On the eve of his execution, with little to lose, Ribbentrop told US interrogators of his having conveyed to Hitler the fears of Germany’s most senior officers that the Red Army was too formidable to take on. Hitler replied, apparently, that this was no longer the case due to the purges Stalin had rained down on his ablest generals. So much for the notion, often raised in communist party circles, that Uncle Joe in his infinite wisdom used the time bought by the Pact to shore up the Red Army!

That said, the question is not whether Stalin was a nice chap – on any number of fronts he clearly was not. Nor is it whether he was the all-seeing astute reader of history his apologists claim for him. The question is whether, given the appalling circumstances prevailing, there were other courses the USSR might have pursued. I am now of the view that there were not.

Hmm. What (briefly – [yes, I know this is impossible]) do you see as making circumstances in Russia unalterable whether Stalin or Lenin was in charge? I agree with Hitler(!!!) that Stalins crazy purges weakened the armed forces – and the Party. His attempted purging of the Kulaks was also mad. But my grasp of this is getting shaky – did Lenin also advocate the latter? It’s 40+ years since I had a handle on this.

Given the forces arraigned against the USSR, I think it a miracle she survived at all, even in so distorted a form.

Sorry – I was rushing in my reply two days ago, so overlooked your point about the kulaks. These richer peasants opposed the revolution, had formed “white brigades” – Mikhail Sholokhov’s novels, most famously And Quiet Flows the Don, make vital reading on this period – and were hoarding grain while British Naval blockade was tightening the noose, and instances of cannibalism were registering. Either the kulaks had to be dealt with, or the revolution was doomed. This is a matter of simple fact and no government in such straits – least of all the imperial powers, with their terrible record of carnage in “the colonies” – would have done other than act with extreme ruthlessness.

In this context both Lenin and Stalin – and for that matter Trotsky – would have been of one mind on what had to be done. On August 19, 1918, Lenin despatched his “hanging order” to commissars in Penza, 300 miles southeast of Moscow:

These were not times for the fastidious!

Correction. I just checked to see it was not Ribbentrop but Keitel – also hanged for war crimes – who told of having communicated to Hitler the concerns of his generals about taking on the Red Army, and of how Hitler had responded. Since neither man had the respect of the Wehrmacht High Command – Ribbentrop viewed as a strutting half wit, Keitel as Hitler’s yes-man – we can only guess as to the levels of concern which led its most senior officers, hardly spoiled for choice since Hitler despised them too, to choose Keitel for so delicate a task.

Thanks Phil, it seems everyone has their anecdotal offerings and a piece I read yesterday served very well as an insight into what Gorbachev thought and said but NOT what he did. I really don’t have much info on the Kruschev, Brezhnev, and Andropov years and as for Yeltsin, words fail me, so have nothing to make a comparison with.

Will look up Prof Hudson and a few others Robert Scheer, 1987 from my files and see what I find.

Trust you are recovered from your bout of Cov19

Susan 🙂

Hi Susan. Re Covid, after fifteen days of very low energy, I feel I turned a corner yesterday. Enough energy, at any rate, to write this piece. And hopefully enough to get back to my third post on Michael Hudson’s 2022 book, The Destiny of Civilisation: Finance Capitalism, Industrial Capitalism or Socialism.

Thanks for asking.

Hi Phil, 2 comments:

1) A number of years ago I visited the (predictably) empty and very much of its time ‘Museum of Communism’ in Prague. Most of it was devoted to the ‘horrors’ of communism and the excitement of the colour revolution but there was a room that focussed on economic planning for the transition to a market economy. Most of this referenced highly detailed work to carefully manage the process to a mixed economy in which the state maintained overall control of the key levers and guaranteed income levels for the population. Unsurprisingly polls indicated overwhelming support for this approach. At the time I left saddened by this lost opportunity – now I am saddened by the acknowledgement that there wasn’t really an opportunity at all.

2) Re the anecdote about Hitler dismissing concerns about the strength of Soviet forces – I have read somewhere (sorry can’t Reference it) that it was the purges in the Soviet army that enabled it to mount such stiff resistance to the German invasion – as there were few attempts to capitulate or broker local peace deals.

Good to hear you’re shaking the impact of covid off and that Michael Hudson is getting your full attention again. I too am working my way through what I think is an excellent book. I’m only about a quarter of the way through (it’s worth making notes in my opinion) and although not hampered by covid I can plead grandchildren!

Hi Bryan. Re your first point, I again recommend Klein for her copious documentation of what took place. Though her focus is mainly on the former USSR, and to a lesser extent Poland, Wall Street rapacity and Chicago School zealotry (whose voodoo economics still hold sway; witness the stupid Liz Truss’s vow to “grow” the UK economy through tax giveaways to the rentier elites who rule Britain) are generalisable. It’s a decade since I read Shock Doctrine. It may well have a chapter on Czechoslovakia.

On the mixed economy, this is a central lesson Deng Xiaoping and his team drew from the USSR collapse and its implications for China rising. As I think you know, the mixed economy – and its underpinning theoretical distinction, as made by Smith and Ricardo, between ‘earned’ (wages + industrial profits) and ‘unearned’ (rentier) income – is central to Michael Hudson’s analysis as cited by you, and in my reply to Susan.

Re your second, I’m wary of being reductive but if I was to elevate one factor as key to the incredible resistance put up by the Soviet Peoples it would be that the Nazi doctrine of racial supremacy, and explicitly genocidal intent of Barbarossa, meant they were not just fighting for land but for survival. (Of course, even a people with its back to the wall needs leadership. It helped that the purges of the army Trotsky had built had not been total: there were still many able field leaders – Zhukov is a prime example – spared.)

Finally, I’ve now read Hudson’s book – much of it twice – and need now to assemble my thoughts in a coherent manner. That too requires energy, and I’m wary of overdoing things too quickly, this being a common error with flu type illnesses.