Dmitry Trenin

On September 8, RT (formerly Russia Today) published a piece by Dmitry Trenin, whose wiki page lists him as:

A member of Russia’s Foreign and Defence Policy Council. He was the director of the Carnegie Moscow Center, a Russian think tank A former colonel of Russian military intelligence, Trenin served for 21 years in the Soviet Army and Russian Ground Forces, before joining Carnegie in 1994.

Since RT is blocked in the West, I can’t overstate the importance of downloading the Tor Browser which is not only:

free and open-source software that guarantees anonymity online, enhances your security and isolates any website you visit so third-party trackers and ads can’t follow you

It also eschews the censorship which Chrome, Edge, Firefox, Safari etc have embraced.

Then again you could simply stay right where you are. Here in full is Dimitry Trenin’s short essay.

Six months into the conflict, what exactly does Russia hope to achieve in Ukraine?

Putin’s latest comments reveal that Moscow’s thinking has shifted and compromise is no longer on the agenda

Last week, Russian President Vladimir Putin referred to Ukraine as an “anti-Russian enclave” which has to be removed. He also said that the Russian soldiers taking part in the military operation there were fighting for their “own country.” These statements carry important implications.

Over the last six-plus months, the mantra of the Russian officialdom has been that all aims of the offensive will be reached. On purpose, however, the specific objectives, such as how far Moscow’s forces plan move into Ukraine, have never been spelled out. This cannot but raise speculation about what the Kremlin is actually hoping to achieve.

The only person who can authoritatively answer that question, however, is the president, and second-guessing him makes no sense. Yet, two things cannot escape close attention. One is the radicalization of Moscow’s position on Ukraine as a result of both Western policies and Kiev’s actions; two is the widening gap between the minimum result of the military campaign that Russia can be satisfied with, and the maximum amount of what the US and its allies can accept.

For about six years after the second Minsk Agreement was signed in 2015, the Kremlin tried hard to get that accord implemented. It would have ensured the autonomous status of Donbass within Ukraine and given the region influence on national politics and policies, including in the issue of the country’s geopolitical and geo-economic orientation. From the very start, however, Kiev was unwilling to cooperate on the deal’s implementation, seeing it as a win for Moscow. Washington, in pursuit of a policy to contain Russia, encouraged such an obstructionist stance, while Berlin and Paris, formally the guarantors of the agreement (alongside Russia), had no leverage in Kiev and ended up embracing the Ukrainian position.

Vladimir Zelensky’s election to Ukraine’s presidency in 2019 initially appeared to be an opening for peace, and President Putin made a serious effort to get the Minsk agreement off the ground. Kiev, however, soon backtracked and took an even more hardline position than before. Nevertheless, until mid-2021 the Kremlin continued to see as its goals in Ukraine a resolution of the Donbass issue essentially on the basis of Minsk, and the eventual de facto recognition of Crimea’s Russian status. In June of last year, Vladimir Putin, however, published a long article on Russian-Ukrainian relations which made it clear that he viewed the current situation as a major security, political, and identity issue for his country; recognized his personal responsibility; and was resolved to do something to strategically correct it. The article did not give away Putin’s game plan, but it laid out his basic thinking on Ukraine.

Last December, Moscow passed on to Washington a package of proposals, which amounted to a list of security guarantees for Russia. These included Ukraine’s formal neutrality between Russia and NATO (“no Ukraine in NATO”); and no deployment of US and other NATO weapons and military bases in Ukraine, as well as a ban on military exercises on Ukrainian territory (“no NATO in Ukraine”). While the US agreed to discuss some military technical issues dealt with in the Russian paper it rejected Moscow’s key demands related to Ukraine and NATO. Putin had to take no for an answer.

Just before the launch of its military operation, Moscow recognized the two Donbass republics and told Kiev to vacate the parts of Donetsk and Lugansk then under Ukrainian control – or face the consequences. Kiev refused, and hostilities began. Russia’s official reason for unleashing force was defending the two newly recognized republics which had asked for military assistance.

Shortly after the start of hostilities Russia and Ukraine began peace talks. In late March 2022 at a meeting in Istanbul, Moscow demanded that Zelensky’s government recognize the sovereignty of the two Donbass republics within their constitutional borders, as well as Russia’s own sovereignty over Crimea, which was formally incorporated into the Russian Federation in 2014, plus accept a neutral and demilitarized status for territory controlled by Kiev. At that point, Moscow still recognized the current Ukrainian authorities and was prepared to deal with them directly. For its part, Kiev initially appeared ready to accept Moscow’s demands (which were criticized by many within Russia as overly concessionary to Ukraine), but then quickly reverted to a hardline stance. Moscow has always suspected that this U-turn, as on previous occasions, was the result of US behind-the-scenes influence, often aided by the British and other allies.

From the spring of 2022, as the fighting continued, Moscow expanded its aims. These now included the “de-Nazification” of Ukraine, meaning not only the removal of ultra-nationalist and anti-Russian elements from the Ukrainian government (increasingly characterized by Russian officials now as the “Kiev regime”), but the extirpation of their underlying ideology (based around the World War Two Nazi collaborator Stepan Bandera) and its influence in society, including in education, the media, culture and other spheres.

Next to this, Moscow added something that Putin called, in his trademark caustic way, the “de-Communization” of Ukraine, meaning ridding that country, whose leadership was rejecting its Soviet past, of the Russian-populated or Russian-speaking territories that had been awarded to the Soviet Ukrainian republic of the USSR by the Communist leaders in Moscow, Vladimir Lenin, Joseph Stalin and Nikita Khrushchev. These include, besides Donbass, the entire southeast of Ukraine, from Kharkov to Odessa.

This change of policy led to dropping the early signals about Russia honoring Ukraine’s statehood outside Donbass, and to establishing Russian military government bodies in the territory seized by the Russian forces. Immediately following that, a drive started to de facto integrate these territories with Moscow. By the early fall of 2022, all of Kherson, much of Zaporozhye and part of Kharkov oblasts were being drawn into the Russian economic system; started to use the Russian ruble; adopted the Russian education system; and their population was offered a fast-track way to Russian citizenship.

As the fighting in Ukraine quickly became a proxy war between Russia and the US-led West, Russia’s views on Ukraine’s future radicalized further. While a quick cessation of hostilities and a peace settlement on Russian terms in the spring would have left Ukraine, minus Donbass, demilitarized and outside NATO, but otherwise under the present leadership with its virulently anti-Russian ideology and reliance on the West, the new thinking, as Putin’s remarks in Kaliningrad suggest, tends to regard any Ukrainian state that is not fully and securely cleansed of ultranationalist ideology and its agents as a clear and present danger; in fact, a ticking bomb right on Russia’s borders not far from its capital.

Under these circumstances, in view of all the losses and hardships sustained, it would not suffice that Russia wins control of what was once known as Novorossiya, the northern coast of the Black Sea all the way to Transnistria. This would mean that Ukraine would be completely cut off from the sea, and Russia would gain – via referenda, it is assumed – a large swath of territory and millions of new citizens. To reach that objective, of course, the Russian forces still need to seize Nikolaev and Odessa in the south, as well as Kharkov in the east. A logical next step would be to expand Russian control to all of Ukraine east of the Dnieper River, as well as the city of Kiev that lies mostly on the right bank. If this were to happen, the Ukrainian state would shrink to the central and western regions of the country.

Neither of these outcomes, however, deals with the fundamental problem that Putin has highlighted, that is to say, of Russia having to live side-by-side with a state that will constantly seek revenge and will be used by the United States, which arms and directs it, in its effort to threaten and weaken Russia. This is the main reason behind the argument for taking over the entire territory of Ukraine to the Polish border. However, integrating central and western Ukraine into Russia would be exceedingly difficult, while trying to build a Ukrainian buffer state controlled by Russia would be a major drain on resources, as well as a constant headache. No wonder that some in Moscow would not mind if Poland were to absorb western Ukraine within some form of a common political entity which, Russia’s foreign intelligence claims, is being surreptitiously created.

Ukraine’s future will not be dictated, of course, by someone’s wishes, but by the actual developments on the battlefield. Fighting there will continue for some time, and the final outcome is not in sight. Even when the active phase of the conflict comes to an end, it is unlikely to be followed up by a peace settlement. For different reasons, each side regards the conflict as existential – and much wider than Ukraine. This means that what Russia aims for has to be won and then held firmly.

*

More? A month earlier on August 4, Dmitry Trenin wrote another short piece, also on RT. Again I have replicated in full.

Russia cannot afford to lose in Ukraine, but neither can the US – is there a non-nuclear way out of the deadlock?

An escalation can lead to a bigger and more dangerous conflict. Are Moscow and Washington ready to take the risk?

The threat of the conflict in Ukraine getting out of control is not just an ever-present concern, but a reality.

The authors of the RAND Corporation’s recent paper, ‘Pathways to Russian Escalation Against NATO From the Ukraine War’, warn US policymakers to be careful in their statements and moves. This is particularly when deciding on military postures, deployment patterns, weapons capabilities, and the like, so that the steps taken by them do not provoke the Russian leadership into pre-emptive or retaliatory strikes, including using non-strategic nuclear weapons, or taking the campaign into NATO territory.

This is totally in line with America’s overall approach of doing the maximum to weaken Russia on the battlefield in Ukraine while avoiding being drawn directly into a war against Moscow.

Seen from here, Washington is clearly escalating its participation in the conflict by constantly testing the limits of Russian tolerance of these moves. It started with the provision to Kiev of Javelin anti-tank systems; it was then amplified to include M777 howitzers and HIMARS MLRS systems; it is now moving in the direction of providing Ukraine with US-made military aircraft and training its pilots to fly them. In addition to the new packages of Western sanctions, Russia is also facing pressure on its geopolitically vulnerable outposts, whether regarding goods transit to and from its Kaliningrad exclave or the status of its forces in Transnistria, a small territory wedged between Ukraine and Moldova. Some refer to the latter as attempts by America’s junior allies in Eastern Europe to open a second front against Russia.

So far, Russia’s actions and inaction have sometimes appeared surprising, even puzzling to US watchers. Moscow has refrained from strikes against transport links to Poland, cyberattacks against Ukrainian – not to mention US – critical infrastructure, or even destroying bridges across the Dnieper River. As for the most concerning step of all – Russia using tactical nuclear weapons – this scenario is irrelevant in a situation where hostilities are taking place on Ukrainian territory with Russian forces slowly but steadily advancing, and a “threat to the existence of the Russian Federation” – the doctrinal condition for such deployment – is out of the question.

Moscow’s failure to respond immediately to high-profile Ukrainian actions, such as the constant shelling of the center of Donetsk; missile attacks against Russian villages and towns close to their shared border; or even the loss of the Moskva, the flagship of its Black Sea Fleet, hit and sunk by Ukraine with the material assistance of the United States, probably demonstrates the Kremlin’s unwillingness to be provoked by the enemy. President Vladimir Putin probably prefers his revenge to be served cold, and at the time of his choosing. It would be safe to say that nothing from this conflict will be forgotten by either side, but at least the Russians have refused to be distracted from their current central task – defeating the enemy’s forces in Donbass and taking control over Ukraine’s east and south.

So far, US-led assistance to Kiev, whether military, financial or diplomatic, has not had a decisive impact on the battlefield. It has certainly propped up the Zelensky government and compensated for the Ukrainian forces’ losses of military equipment, thus contributing to the slowing down of Russian advances, but has not turned the tide of the war. One may conclude that the Kremlin sees no need, for now, to do things that would breach the resistance of the Biden Administration to domestic U.S. demands for a more rapid escalation of the US involvement in the conflict. Jake Sullivan’s recent comment to the Aspen Strategy Group, demonstrating the reluctance of the White House to provide ATACMS systems to Kiev, suggests that this approach has some value.

Looking ahead, one should expect more US escalation in any scenario of the evolution of fighting in Ukraine – whether Russia continues to gain ground (and integrate various new territories into the Russian Federation), or Ukraine mounts a counter-offensive (which so far it has failed to do). Russian officials express concern that a Ukrainian provocation presented as Moscow’s use of chemical weapons – which makes no military or any other sense but would certainly be believed in the US as a major egregious act by the Russians – could lead to Washington climbing abruptly up the escalation ladder.

Things may become even more serious, however, if the US or its NATO allies enter Ukraine, or otherwise become directly involved in the conflict; if the material assistance which they provide to Kiev starts making a major difference on the battlefield; or if those weapons are used to strike significant targets on Russia’s territory, such as the Crimean Bridge. There are parallel American concerns about Russia attacking transshipment points on NATO territory, launching significant counter-attacks against the United States or its allies, and using weapons of mass destruction. The last point has already been discussed, and as to the previous two, they could be in response to an adverse turn of events in the theater of operations.

Neither Russia nor the US can afford to lose in the conflict now raging in Ukraine. However, the difference between the situations faced by Washington and Moscow is huge. For the American leadership, a failure in Ukraine would be a strategic setback, politically costly both at home and internationally; 1 Europe for the Russian leadership, the outcome of its special military operation is an existential matter. In an asymmetrical conflict like this one, this amounts to an escalation advantage, if not dominance. What is vital for the two countries and the rest of the world is that this fight does not cross the nuclear threshold.

* * *

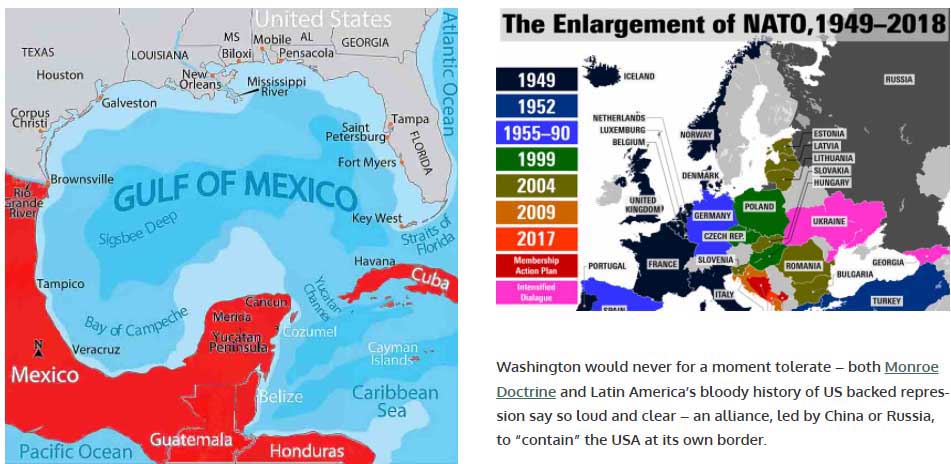

- “For the American leadership, a failure in Ukraine would be a strategic setback, politically costly both at home and internationally …” I fear Mr Trenin understates what is at stake for US elites. Their economy, like the UK’s, relies on a global exploitation which Eurasia’s rise threatens. With manufacturing outsourced to the benefit of a rentier class, there is no fallback position should the dollar’s rule falter. These matters go beyond the military and geostrategic matters in which this writer has clear expertise. Since the proxy war in Ukraine is a key part of US-led efforts to contain Eurasia – not an existential matter for Americans at large, the way it is for Russians at large, but ultimately one for those whose interests drive US policy – the dangers are greater than even he realises.

““For the American leadership, a failure in Ukraine . . .”

I beg to differ (on the assumption, perhaps dubious, that the US state – deep or otherwise, is not completely insane).

The US swallowed defeats in Vietnam, Iraq, Syria and Afghanistan without much difficulty. Defeat in the Ukraine would and could be covered by an account of how the huge sanctions regime is ‘working’ – even if ‘working’ means ‘working against our “allies”‘. Also, the US has to keep in reserve even more capacity to engage with China – and who knows where that will go in future. If they go crazy over the Ukraine, then the door would be open for China to take over what was left of the entire ‘west’ (unless they decide to take out China too). But this would be completely bonkers.

Russia has a very, very large, sparsely occupied territory and China has a very, very large population, while the US has a not so large and not so huge population in comparison. The odds are that in a post nuclear age (if there is one) China and a part of Russia would be the ‘winners’ in very very inverted commas, plus Africa and South America. I’m afraid the UK is to be a blasted wasteland, possibly with a very, very demented Big-Ears and Noddy fighting for the last Rice Krispie in a very, very deep and dark basement.

Sorry about all the ‘very, very’s – they seemed essential.