All you need is love. The Beatles

I see friends shaking hands, saying how do you do? – they’re really saying, I love you. Louis Armstrong

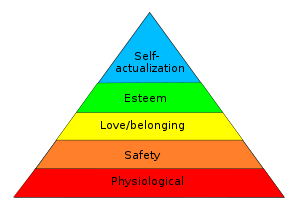

A recent post saw me invoking Maslow as if his ‘hierarchy of human need’ was unproblematic. Its strengths are simplicity and intuitive appeal, but they’re also its weaknesses. Some intuitive understandings – the sun obviously orbits the earth … you can’t possibly explain the human eye as product of natural selection and random genetic mutation – are just plain wrong. Others are either only partially true, or routinely misinterpreted.

Common sense comes drenched in ideology and Maslow’s hierarchy, like a good deal of social psychology and all cognitive psychology, is a case in point. At issue is a Model of Man, Woman too, as lone problem solver.

A Holocaust documentary I saw decades ago interviewed a Theresienstadt survivor, a woman in middle age. Amid that hell on earth she, then a teenager, and her mother had come by a bowl of thin soup but neither would take first sip. Only after much argument and remonstrance was it agreed they’d take turns, one mouthful at a time.

After a few turns it became clear that, with every sip, each diner was slyly taking a little less – nothing too obvious – than the other on her previous turn.

More argument. More remonstrance.

Finally the perfect solution was agreed. They’d still take alternate mouthfuls, but now two quite separate acts – gathering soup in the spoon, and swallowing the same – had different agents: mother serving daughter, daughter serving mother; each dip of the spoon filled to capacity.

*

Holocaust accounts are replete with such stories, and others offering equally deep insights into the human condition. Read Victor Frankl. Listen to Lee Hall’s Spoonface Steinberg – the radio monologue that, on first airing in 1997, had big hairy lorry drivers pulling off the road, unable to drive for tears.1

[ezcol_1half]Maslow has love halfway up but that surely reflects the bourgeois take, under that lone problem-solver model, on what the stuff is. The Beatles sang truer than they knew, and Maslow can’t explain those loving Theresienstad spoonfuls. Nor why, as the beautifully dying Spoonface tells us, kids in line for the gas chambers played hopscotch in the dirt.[/ezcol_1half] [ezcol_1half_end] [/ezcol_1half_end]

[/ezcol_1half_end]

How can Maslow be so right and yet so wrong? There’s a clue in something I wrote over two years ago for a quite different purpose:

We have dual natures, you and I. On the one hand we are supremely social animals. Unlike pike or tigers or black widow spiders, who associate only to mate or commit internecine violence, we need one another. Ill equipped for solo survival we must engage collectively with nature to feed and shield ourselves from the elements. But we are also standalones. If a brick drops on your toe it’s you, not me, who dances like a demented dervish. Your pain may even, for this reason or that, make my day. Indeed, I may have intentionally caused it since not only are we separate but at times play zero sum games; some choiceless, others of exquisite perversity.

Our dual nature creates tensions whose imperfect resolution required the development over millennia of morality and etiquette, religious and legal stricture. Had we evolved for either unambiguously solitary survival or as purely social beings, such codes would be irrelevant. In the first scenario conflicting interests would be settled by undisguised force, or its threat, while in the second there’d be no conflict at all since your interests would be mine. It’s fair to say our ideas of right and wrong, good manners and bad, are all by way of managing – not always successfully, far less equitably – fault lines arising from our nature as social but individuated beings.

No form of organising social relations to fulfill our material needs – classless hunter-gatherer, slave based, feudal etc – comes close to capitalism in its one-sided emphasis on the individual aspect of our dual nature. Viewed in this light Maslow’s explanatory successes and failures pose no great conundrum. Our worldviews are suffused with a psychological model of ourselves as atomised: solo decision makers, interacting in a global market place at the end of history. We are latter day Robinson Crusoes, herded or hunting in packs as the case may be, but either way our internal landscapes are by such reckonings those of Desert Island Man; transplanted to, but not transformed by, a brave new world of lonely crowds.

As homo economicus we became, some two centuries ago and for the first time in the 140,000 years of our currently evolved form, not simply the creators of wealth, or even of wealth in the shape of commodities. Our labour power is now itself a commodity, for sale in hourly units. By this fact are we alienated from ourselves and from our fellows. Estranged from one half of our totality, love is no longer the glue that binds us, your interests being mine, and mine yours, but a thing ethereal, mysterious and above all outside of ourselves; yearned for, yes, but only when the time is right and more basic needs fulfilled.

Yet what does that tale from one of history’s darkest moments – the mother did not survive, by the way – tell us, if not that the fab four were right and nothing is more basic than love? Maslow can’t account for that sharing and neither – for all its explanatory power on other matters – can Dawkins’ selfish gene.

(Not even when we avoid the schoolboy howler of conflating gene with organism.)

For all their brilliance of insight, both Maslow’s ‘model of man’ and the clear but narrow lens of Dawkins and Darwin are pinioned by the same half baked grasp of who we truly are.

* * *

Maslow’s intellectualising, theorising, analysing and charts amount to pointless posturing. Simply speaking, we individuals are what we are.

Bit harsh on Maslow, methinks. No disputing, however, that we are what we are.

Good article Phillip.

Couldn’t get to the end of Maslow’s interpretation and decided the guy had a serious deficit on understanding so many people who just didn’t fit into his “chart”. Ended up believing his intellectual theories were driven by his own misconceptions about what constitutes realism and that his bias was borne of his own experiences more than his fellow human beings who are as diverse as they are individual. His whole premise seemed to be off kilter and far from celebrating individualism he condemned it – by pigeonholing people. I think he was more wrong than right, but that’s just my take and I am no intellectual. Assigning values as though they were elements of a mathematics equation is never going to find traction with me.

Thanks Susan. I think all human sciences – economics, sociology and history too – are flawed by that lone problem solver model, product of bourgeois society. I don’t say psychology’s findings are worthless, far from it, but even the insights of Bowlby on attachment, Asch on conformity, Milgram on obedience etc are limited – how could they not be when there’s only so far any of us can go in piercing the veil of dominant ideology? – by that individualistic take on our humanity.

The acid test of knowledge is predictive power. Many bodies of knowledge can account for the past in ways highly plausible, but science alone takes risks. “Under these specific conditions”, it says, “this specific outcome will occur”. The nature of human sciences, where we are dealing not with atoms and molecules but beings with Intentionality and Will, necessarily offers lower predictive power than in natural science. But what further weakens it is capitalism’s ideology-laden understanding, usually invisible to and unquestioned by us, of who we are. Unable to understand ‘society’, Mrs Thatcher famously dismissed it as non existent. For his part Maslow could not predict that shared bowl of soup in Theresienstadt.