Deaconess: For all who are victims of trafficking and enforced prostitution …

Choir singing: Lord hear our prayer.

Deaconess: For all who are victims of violence, racism and murder …

Choir singing: Lord hear our prayer.

*

I’ve had race on my mind for quite a while now. My Venezuela posts may have focused on other angles – on oil and petrodollars, on Monroe Doctrine and its Roosevelt Corollary, on crippling sanctions and threats of military assault, and on promises by Juan Guaidó to backers within and without the country of a feast of privatisation – but all are mediated by race. Study the images offered up by corporate media as proof of Maduro’s unpopularity. The less credulous will see, in these faces of white incandescence – in a land where the poorer you are, the darker your skin – why the nation’s elite called Hugo Chavez, monkey.

But this isn’t a Venezuela post. It’s just that, with race already in my thoughts as I came through customs at Louis Armstrong International eleven days ago, my experiences in New Orleans – the most welcoming first world city I ever set foot in – did nothing to dispel it.

America, everybody knows, lives and breathes racism. Like Australia, Canada, Israel and New Zealand it is a nation state built on ethnic cleansing. And like Australia, Canada, New Zealand and most of Latin America its ruling class grew and remains stinking rich on the back of slavery. Said Ali, the slave descendant who showed us round Whitney Sugar Plantation in the Louisiana bayou,1 ‘you do not build a nation as powerful as this one by paying people to do it’.

America’s racial divisions are in your face. It’s true that Western Europe’s prosperity, and the ‘open society’ premised on it, are steeped in the blood and tears of colonialism and slavery. And yes, that prosperity is still firmly dependent on imperialism and planetary apartheid, underwritten by armed might. But within Fortress Europe racism is now less visible. By contrast, on race as on other matters, America struts its stuff: its divisions Out There in ways that British, Germanic and Scandinavian sensibilities find, more through naivety and amnesia than hypocrisy, distasteful and alarming.2

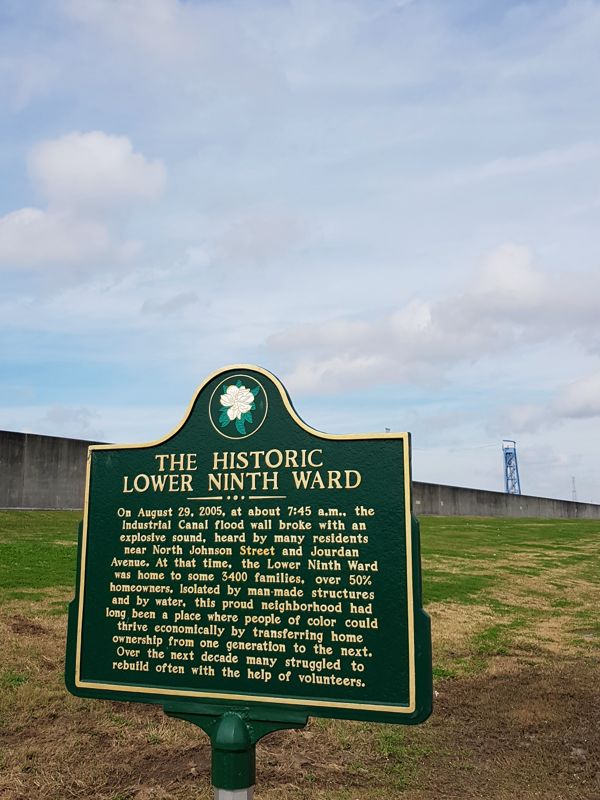

New Orleans now has a black (and female) mayor. Mixed race couples stroll St. Charles Avenue and Beyoncé has a grand house in the leafily colonial, predominantly white neighbourhood we stayed in last week. These are not small things in a deep south fast reinventing itself but neither is the fact that, of a score of streetcars I rode, none had a white operator. The men digging up the roads, bringing the mail and collecting the trash? All black. Ditto the women in fast food outlets (minimum wage, no tips) else pacing the streets to ticket unlawfully parked cars. Ditto those who most took the hit when Hurricane Katrina paired up with official incompetence and worse, that night in 2005, to leave a wake of destruction to this day visible in the black ‘hoods squeezed between ocean and Mississippi, and lying below the levels of both.

*

I should say why I was in New Orleans at all. Jackie’s daughter graduated in law, last summer at Bristol. She has a six month internship with a husband and wife team, Susana and Nick, who represent the last glimmer of hope for those convicted of capital murder. To be on death row in Louisiana, as in any death penalty state, you will be poor. Which makes you disproportionately likely to be a person of colour. All the more so if your victim was not.

I will write on this, and on my conversations with the impressive Nick and Susana – he native to the city, she a New Yorker, both white – but not now. Suffice to say that Susana gave us a personal and enthrallingly detailed tour of Lafayette,3 one of several remarkable cemeteries in this endlessly fascinating city.

She then took us to Lower Ninth to meet a man who lost a mother and two granddaughters to Katrina. Now good friends, Susana and Robert Green met when volunteers from her church brought their various skills to bear on the relief vacuum created by the collapse of authority in a catastrophe biblical in nature and scale.4

Robert is impressive. I may not share his views on the Obamas, whose Christmas cards to him he proudly showed, but have better manners than to argue the point with any black American on first encounter, least of all one who lost so much under Dubya’s watch. (On which he’s damn forgiving: ‘I used to be angry with Bush, but now know there was nothing he could have done’.) Ditto the effectiveness or otherwise of interventions by Brad Pitt, who stands beside Robert in a photo transferred to the t-shirt he also showed us, apologising for not wearing it as he didn’t know we were coming. This man saw things most of us glimpse only in our worst nightmares but, despite or even because of that, bounced back smiling. Deeply impressive. Here he is with an equally impressive Susana.

*

I hope, notwithstanding my vow to cut back on air travel, to return to New Orleans. A week could never be enough, even though – thanks to Nick, to Rhianna and her brilliantly welcoming housemates, and above all to Susana – we packed more in than a month would otherwise have allowed.

The food alone merits a post. Here’s my salmon burger, one of the house specialties at a low cost eatery on Magazine Street.

Naturally, we did Cajun – gumbo and jambalaya but not, alas, catfish pie – while one night Nick and Susana took us to dinner, preceded by cocktails, at one of their favourite restaurants. There I had blackened redfish in an exquisite sauce, every mouthful an explosion of flavours.

Speaking of explosions, this city is the birthplace of jazz: that melting pot where blues and work songs sacred and secular, ragtime syncopation and the folk music of a dozen cultures fused in one of the three great musical forms twentieth century America enriched the world with. Back in the day the funeral bands would play it sombre on the way to Lafayette, St Louis and all those other baroque bone orchards. But on the way back? That was another story; all restraint cast off in a riotous, life affirming din of brass and percussion.

We went to two gigs: one for fifteen bucks at the Snug Harbour Bar on Frenchmen Street, where a piano-led quartet of East Coast Cool took in Miles, Mingus and Monk; the other an open mike session where the outstanding house band, Black Redemption, backed anyone taking the stage. Given this, and free entry, I’d expected mixed quality from earnest amateurs. What we got were seriously bad cats grabbing the op to plug themselves, their bands and in one case a radio show. Stunningly good; my personal high point a twenty minute improvisation with devastating solos from horns, keyboard, drums and electric cello – woven together by periodic returns to the jazz chant, I’m sorry ’bout your daughter …

Then there were the two cracking blues outfits onstage as we supped and dined in a bar across from the French Market. Best of all though were the trad sounds of Louis, Bix and Mr Jelly Lord on the streets and squares; virtuoso bands with virtuoso soloists in a city whose musicians get peppercorn rent housing, and every encouragement to busk in tourist hot spots.

Time we heard some of it, methinks. Here’s Jelly Roll “I invented Jazz” Morton – as channelled through Wynton Marsalis in New Orleans Bump.

*

I should mention our trip to the bayou, booked on a day of radiant sunshine with temperatures nudging seventy fahrenheit but made on the coldest day of our stay, low fifties with all right thinking alligators skulking on the river bed. Of the three we saw, one had the tell-tale albino of generations of captive inbreeding, another was a baby kept in a picnic ice box by its boatman and tour guide owner. But one wild specimen did glide across the bayou twenty metres from our boat. I snapped it with my 70:200 lens and had a decent picture but, for reasons I still don’t comprehend, my bayou pictures – and all the best music shots too – are among hundreds gone to the planet of lost photos.

But Someone Up There is watching out for me. I still have scores of pictures taken on my phone, while those 7D images that survived include most of those taken on what, in the face of stiff competition from all the above plus the first of the Mahdi Gras parades, was the highlight of my trip. I mean Nick’s and Susana’s church, Peter Claver Baptist in the Treme’ (“Tre-May”) District. Treme’ is another of the city’s jazz heartlands, which goes some way to explaining how its choir wins jazz as well as gospel contests across the USA.

Here’s Nick, one of three white members of a thirty strong choir, taking his seat at start of play.

And here’s how things were shaping up a while later.

The rhythm section.

The drummer, her kit hidden from my lens by the keyboard between us.

This lady read from the scriptures. She was on fire. I’ve seen Shakespeare done in Stratford and West End theatres by actors who couldn’t hold a candle to her.

A few minutes in, the deaconess bade “our visitors” – meaning Jackie, Rhianna and yours truly – stand up. Already feeling about as inconspicuous as Raymond Chandler’s tarantula on a dinner plate, we now basked in the warmth of rapturous applause. The lady at the end of our pew came over to take us by the hands. I don’t know how Rhianna felt – at her age I’d have been mortified, though I had all manner of hang ups she doesn’t – but now, to be on the receiving end of such warmth and loving acceptance? That was really something.

Susana told me I could take as many pictures as I liked; no one would mind. What, even with Canon and bazooka lens? Zero problemo, she assured me as, two pews in front, a bloke turned to strike up a conversation on Canon v Nikon, and the merits of my L-series 70:200 f2.8 lens.

This was church, Jim, but not as we know it.

Least of all Baptist church. Rhianna had said beforehand that her bosses’ church was Catholic, with Nick in the gospel choir. As a reluctant graduate of Spurgeon’s Baptist Homes for Children on the one hand, lover of gospel music on the other, I knew this didn’t stack up when gospel choirs are exclusive to the black Baptist churches of America’s deep south.

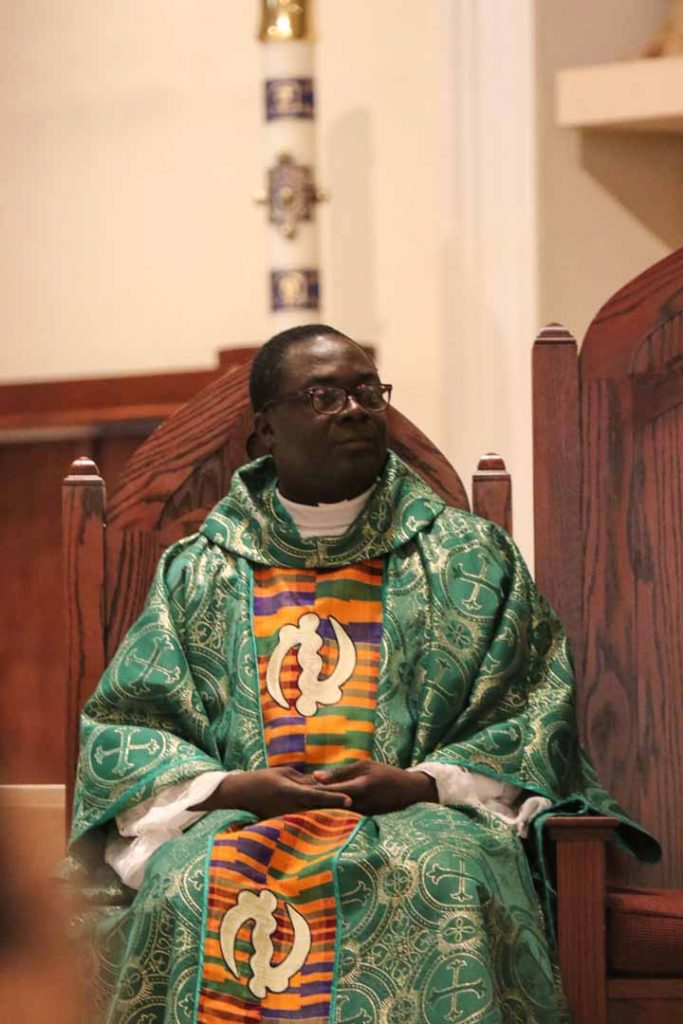

But here’s the thing. Under Sun King Louis Quatorze’s Code Noir, the slaves of Louisiana were compelled to observe the Catholic faith. Later, especially after the Civil War, some turned to nonconformism, which in these parts meant Baptism – rigidly segregated of course. With some members of a family remaining Catholic, while others embraced Baptism, the two co-mingled I guess. That’s my theory anyway, and it does have the merit of explaining how a Baptist Minister gets to dress up in a way that would not do at all, really it wouldn’t, in the dour chapels of the Rhondda. Or for that matter Pennsylvania.

For all his finery, the man has a decent line in dry humour. Midst a homily on mendacity, he made reference to white lies – adding quietly that “I didn’t know lying had a race”.

*

I’m not a believer in the deist sense. What I do believe in is the depth of communion enabled when men and women come together in the name of something bigger than themselves. The more so when those same men and women, having experienced and continuing to experience humanity at its worst, refuse to be broken or embittered by it. That, too, is really something.

Last but not least, to have the privilege of being welcomed with such warmth and dignified bearing is also to be immersed in an extraordinary tapestry of sound. My experiences of church – with the sole exception of one in Sheffield, its minister a white man I hold in high regard and was once my next door neighbour, but its congregation predominantly African and Caribbean – is of endless tedium. You sang a hymn – occasionally with rousing tune but more often a dreary dirge – then heard a boring sermon. You sang a second hymn, heard a bible reading lifelessly intoned. You sang a third hymn, then prayed out loud. Finally there’d be announcements, hymn number four and then they’d let you go, hopefully to a decent Sunday roast.

Not so at Peter Claver. I’m a fan of those seamless blends of prose, poetry and music that BBC Radio Three goes in for every now and then. So it was here, the action shifting continuously between choir and musicians, minister, deaconess and congregation: with none of the joylessly sliced up controls of the churches of my childhood, their highly regulated and limited audience participation a far cry from these as-and-when interjections from the floor of “amen” and “yes indeed” (let alone leisurely exchanges re camera kit). I don’t suppose I’ll ever go Christian, but if New Orleans wasn’t quite so far – and I hadn’t vowed to cut back on long haul flight as well as short – I could see me dropping by once in a while. If they’d have me.

* * *

- Too humid for cotton, the bayou was perfect for indigo until its ousting in the early nineteenth century by synthetic dyes. The planters turned to sugar and Louisiana grew rich. It was dubbed the Gold Coast for the fact that, prior to a Civil War fought to free up southern labour for northern factories, half of all America’s millionaires lived here. Slave life expectancy was ten years from arrival, and the threat to “sell you down river, boy” an effective way of keeping order on plantations a thousand miles distant. On a related matter I’d taken as read that when, decades before Abolition, America signed up to the ban on the slave trade, it did so due to arm twisting from European Powers led by Britain. True, but as my visit to Whitney Plantation showed, those powers were pushing a door already opening. Slave revolts in the Caribbean, Haiti’s and San Domingo’s in particular, left the American states fearful (the trade by this point as much within the Americas as from West Coast of Africa) of importing revolution. Why risk that when they now had sufficient stock to supply their needs through breeding? Also related is the fact that Whitney limits its focus to slavery in the American South, with only passing reference to its wider history – and the word’s origins in the sale of Slavs around the Mediterranean and North Africa – and none at all to the dreaded Middle Passage. When the slave trade itself is factored in, the totality of horror is qualitatively comparable to the Holocaust while quantitatively vastly exceeding it.

- I’ve argued elsewhere that the business case for racism within the West is eroded by advanced consumer capitalism. But for some time after its drivers have passed their sell-by date, it may, for reasons of demography and populist politics, survive in yet more virulent, darkest-before-dawn forms.

- Lafayette Cemetery, in the city’s Garden District, features in a terrifying scene in the Tommy Lee Jones/Ashley Judd film, Double Jeopardy. What gives this and other New Orleans cemeteries such gothic appeal is the fact that, owing to the high water table – dig more than two feet down and the hole floods – bodies are not interred but stored in marble edifices of varying grandiosity. Coffins are of cheap wood not through penny-pinching but because, in family crypts, they must rot quickly to allow the bones to fall and make room – after a statutory minimum year and a day – for the next incumbent. Death stalks this city in gothic, comic and – witness the frequency of the death march amid the irrepressible jubilance of Jelly Roll Morton et al – musical guise. Two of a thousand post Katrina complications were distinguishing old corpses from new, and getting the former back where they belonged on a DNA basis.

- The Ninth Ward has two parts, both below sea level and bounded to the south by the Mississippi; to the east by Lake Pontchartrain, the vast estuarine lagoon lying between the city and Gulf of Mexico. Katrina’s subsequent deluge flooded Upper Ninth, a black neighbourhood upriver from Lower Ninth and separated from it by a levee the size of Manchester Ship Canal. As the water rose, the occupants of timber houses – built by ancestors who’d bought their freedom and tiny plots in what was then malarial bayou, using swamp vegetation for materials – had time to evacuate or take to their roofs. Some drowned; many were rescued. It went harder for Lower Ninth. Inevitably, given that lived nightmare and the chaos of a city abandoned, conspiracy theories are rife. A black cab driver told us she’d heard the crack that night of controlled explosion at the levee. Nick takes the view that such sounds, reported by many, were of barges hurled by the storm against the banks to effect devastating breaches. What no one disputes is that the US Army Corps of Engineers, which had decades earlier cut the levee for flood defence and to transport oil up the Mississippi, did a lousy job. Nor that federal government immunity from lawsuits over flood control was one of many injustices laid bare or set in motion by Katrina. Nor yet that, unlike the more gradual flooding of Upper Ninth, the bursting of the levee sent thousands of tons of water crashing down on Lower Ninth, its then dense housing spread out like a rape victim directly below the multiply ruptured embankment. Many drowned or otherwise perished there and then; others were swept away in houses dashed from pillars built to keep them above high water levels, not to withstand these sideways-on forces of a power no one had envisaged. Robert Green’s granddaughters drowned this way. Days later he recovered the body of his mother, traumatised by injuries sustained as her home careered and collided with lethal debris, including other homes afloat with their own human cargoes.

https://www.google.ca/search?q=planxty+lakes+of+pontchartrain&rlz=1C1GCEA_enCA748CA748&oq=Planxty+Lake&aqs=chrome.1.69i57j0l2.12347j1j8&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8

Did you check out the Charter schools?

Nice love song, bevin. Thanks. I didn’t check out the Charter Schools for the simple reason I’d never heard of them till now. My knowledge of Katrina and its aftermath is infinitesimally small, mainly what I’ve gleaned from Susana and from wiki. I’ve nevertheless set aside a couple of pieces for later reading, including this from the New Yorker.