The character of Clara Dawes; she of one of the dozen novels, all read before I turned sixteen,1 which most moved me in boyhood, is nut-shelled on this A-level primer site:

Clara is wife to Baxter Dawes, whom she could not get on with. A friend of Miriam (who introduces her to Paul Morel) she lives with her mother. She’s a suffragette, resentful of how her marriage has worked out. Paul believes she is a “man hater” but, as he gets to know her, feels she is deeply sensuous and “needs a man” to feel loved and that her single life makes her depressed. Clara insists Baxter was cruel and this is why she left him. Paul and Clara have a passionate and physical relationship, but little in common intellectually. Clara is strong, active but reserved, and finds it hard to fit in with the factory girls when Paul gets her a job. She gets on well with Mrs. Morel, however, who prefers down to earth Clara to the saintly Miriam …

I guess Paul did his Sunday courting of Miriam and Clara (and their creator of Jessie Chambers) in the pit blackened country of an Erewash2 within easy reach of his Eastwood home. As one beginning his own courting – a tad later than David Herbert but still in an era when a lad lucky enough to get a bit of nookie likely as not got it outdoors – in the pit blackened country south of Barnsley, around Elsecar and Hoyland Common, I empathised with Paul Morel and still have an affinity for post industrial landscapes.

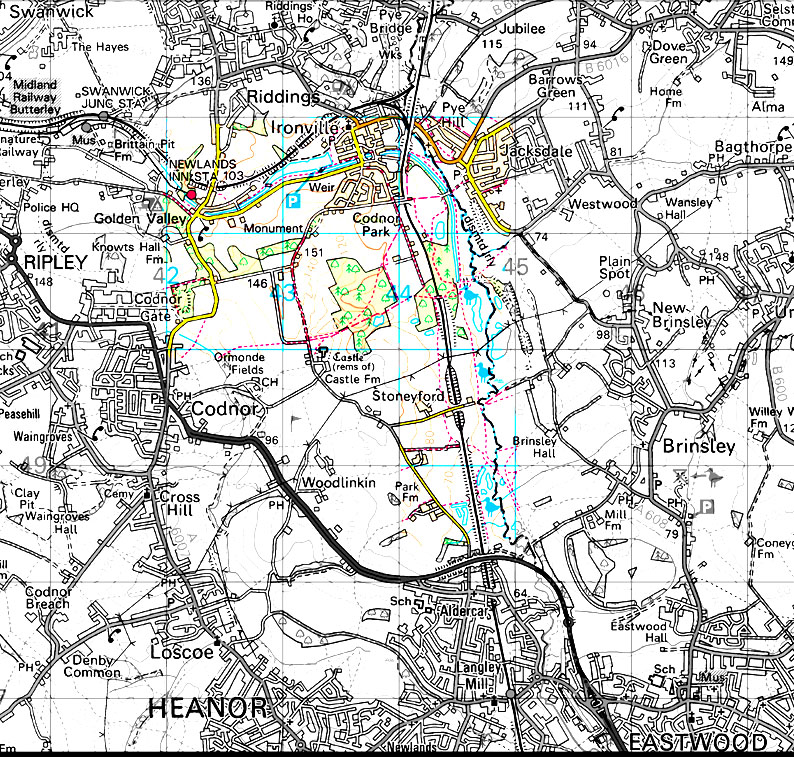

Yesterday I picked up my pal Bryan in the ghostlike car park at IKEA. We went due north through Eastwood – passing the plaque-marked road of DHL’s birth – to a carp fishery across the lane from and due east of Park Farm. To the north-west, the talented town of Ripley. To the northern edge of our walk, the dam and former industrial villages of Ironville, Pye Hill and Jacksdale. All would have been familiar to Paul Morel et al – and even now, more than a century on, there’s much they’d still recognise.

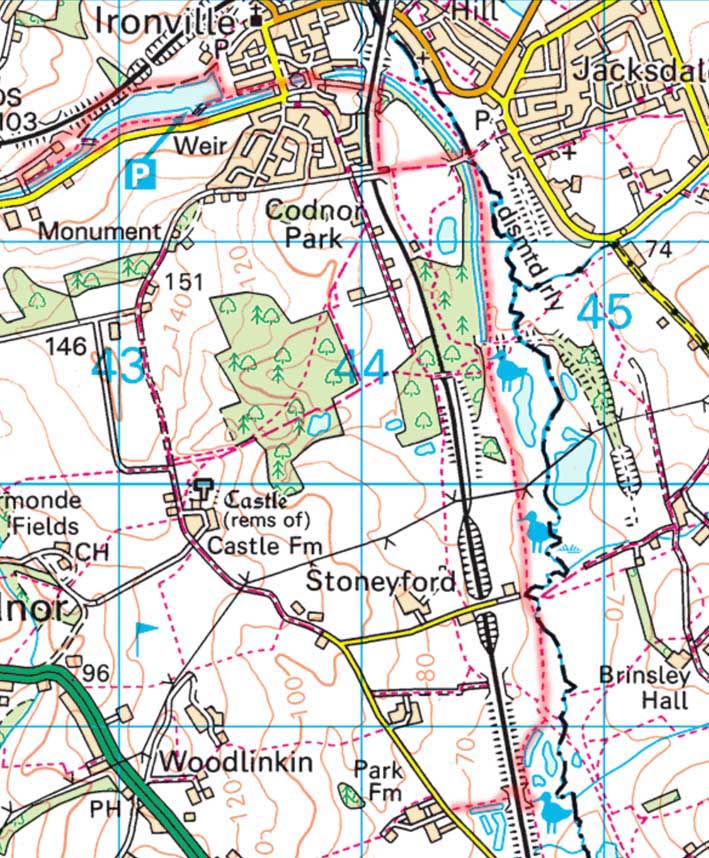

Here’s the close up.

Our route was more varied than the traced path suggests. We were on a nature reserve in the Erewash valley, where pitheads and ironworks once shared the space with small farms. This part of the world has many such reserves, all steeped in industrial heritage. Close to small and medium population centres, they are well used. Bird watchers have trodden countless lesser paths, unmarked, some of which we took – constrained less by rights of way than by marsh and mere, by railway track and by the river itself.

The carp fishery where we parked.

First glimpses of the Erewash, on its southerly way to join the Trent a mile south of Long Eaton, reached by a muddy lane passing under the rail track. The thing to remember is that Erewash rhymes with ‘very posh’. Efforts to convey this vital truth in verse led seven months ago to my now waning passion for the limerick.

One of many small meres, havens for resident and non resident bird species. In the distance is Brinsley, at whose long gone colliery Lawrence’s miner father had worked.

We saw herons, terns and gulls – as well as wrens, robins and other species I couldn’t ID – and were told kingfishers are often seen. Early afternoon a kestrel flew low overhead.

Cromford Canal, long fallen into disuse. From here it’s fifteen miles to Cromford in Derbyshire’s Amber Valley, where Sue and I walked 363 days ago. That’s way over to the west.

Here at the eastern end, where the south-flowing Erewash (off camera to the right) marks the Derbyshire-Notts border, we’re near where Cromford Canal once joined the Erewash Canal, as canoed a time or two by Jasper and me.

This canal by contrast is dry for much of its length. The Cromford End holds water but here we see only a few pockets of the stuff, maintained for the encouragement of aquatic species.

When the towpath switched bank – or, as it did here, had to traverse an incoming spur canal3 – bridges like this allowed horses pulling the barges to cross easily, without need to unhitch.

The large dam with Ironville and the dam wall (off-camera to the left) at its eastern egress.

Back in the day it would have supplied water to – perhaps even driven the pre-steam wheels of – drop forge and foundry, tiny by later standards, to make Britain workshop of the world. Today we saw third millennium strollers taking the sunlit air, a few queuing at a mobile greasy spoon.

Two men fished for pike, another (less probably) for carp. None, carp man confessed, had had so much as a bite. Speaking of which, we were ready for lunch.

At a bench in the sun, overlooking the dam, we took out our goodies. I’d cooked a stir-fry with noodles that morning, cooled in the garage, ladeled into tupperware. I’d even brung chopsticks. For afters, Bryan supplied coffee and shortbread. Replete, firmly renouncing brandy and cigars, we resumed our perambulations.

We’d done with the kith and kin. Now the talk was of politics and little else. There was the US election, and liberal responses, to go over. And the stepping up of hostilities on Russia and China. (We’d yet to hear of that day’s murder of Iranian nuclear physicist, Moshen Fakhrizadeh.) And Owen Jones’s new book on ‘Corbynism’, which Bryan is three-quarters of the way through, while I’d the previous day skim-read a LRB review. This led to the strengths and weaknesses of Jones’s worldview, and to Jonathan Cook’s dissection of his and Monbiot’s role at the Graun:

Most of the Guardian’s writers pander squarely to the general “educated liberals” market. But some, like Monbiot, are there with a more specific purpose: to mop up sections of the population that might otherwise stray from the Guardian fold.

Owen Jones is there to mop up leftwing supporters of the Labour party to persuade them the Guardian is their friend, even while the paper was helping to destroy Corbyn. Jonathan Freedland is there to reassure liberal Jews the Guardian is on their side, which he did by playing up evidence-free smears that Labour had a special antisemitism problem. Hadley Freeman is there, as is Suzanne Moore, to represent liberal women invested in identity politics and keep them away from class politics.

The Guardian is a corporation that makes sure its columnists cover as many liberal-left bases as possible without allowing any real challenge of a neoliberal status quo.

Monbiot’s position is the most absurd, the most plagued with contradiction: he must sell extreme environmental concern within a newspaper entirely embedded in the economic logic of the neoliberal system that is destroying the planet.

The talk is always free flowing when Bryan and I meet, these days invariably for a walk.

Looking north-east towards Jacksdale.

On the Notts bank of an adagio stretch of the Erewash, I thought I’d spied Hank Marvin of the Shadows. But a brilliantly devised experiment – me waving free hand and shaking each leg in turn, while closely monitoring the results across the county line – left little room for doubting that I was looking at my good own self; that ‘guitar neck’ in all likelihood my 100:400mm lens.

One for my burgeoning Goods Train Crossing Muddy Cart Track series.

And here, to finish off, the final resting place of last year’s motors.

After which we got back in the Reliant Robin and tootled home.

*

- The full list in order of encounter being: Her Benny, Coral Island, Uncle Tom’s Cabin and its soulmate (good owner-bad owner, good owner-bad owner, then they die) Black Beauty, The Mill on the Floss, Huckleberry Finn, Sons and Lovers, Quiet Flows the Don, The Grapes of Wrath, Catch-22, The Tin Drum and Howards End. (The author of that last helped redeem Lawrence who, at his death ninety years ago, aged forty-four, was deemed by the literary great and good to have wasted his talent on writing pornography. In an obituary, EM Forster called him the greatest imaginative writer of the day.) I suppose I’ve read books as good or better since, but nothing has quite the impact, does it, of a powerful read in that magic decade between six and sixteen?

- Unnamed on the maps shown here, the Erewash runs south easterly between Ironville and Pye Hill, before turning due south. Its course, overlaid and obscured by the black path marker, stays east of the railway track, also running southwards, and one or two hundred metres (a tenth or a fifth of a grid square) west of longitude 45.

- Spur canals, some as short as two hundred yards, few longer than four miles, might serve a single mill and would have been constructed at the owner’s sole expense. By contrast, the much larger canal infrastructure of the main circuits were beyond the pockets of even the richest individuals. The establishment in the colonial period of limited liability and joint stock ventures is an unsung factor (relative to those of slave trade, colonial plunder, maritime power, Britains abundance of fast rivers and its rich deposits of coal and iron) in kick-starting the world’s first industrial revolution. One inhibiting factor in Iberia’s glacial transition to capitalism was that cheap gold and silver from the Americas had held back such developments in Spain and Portugal.

Great pics of a brill walk (and talk) Phil – and just look at that sunshine – just what you need on a late November day.

As Ray Davies put it, “thank you for the day[s] …”

Some very nice shots there Phil. I might have done some macro shots of the old cars surfaces, but that’s just me! Yours have plenty of atmosphere.

Thanks Jams. You might check out the pics on A Toton Sidings Sunday, posted back in April.