Wednesday: day two: 07:15. The weir comes as an unpleasant surprise.

I overnighted on Branston Golf Course, a mile upstream of Burton, to arise at six. Sleeping and bivvy bags rolled up and stowed, my scan of parched grass – short cropped, flattened and free of dew – showed no items left behind. I lowered boat and kit to the shingle beach I’d hauled in at the night before, then scrambled down the short vertical bank to join them. My laden canoe no longer an airbed, but pushed out into deeper water to resume its primary function, I threw myself aboard – if there’s a graceful way to get into a floating canoe, nobody told me about it – to be back on the Trent for 06:20.

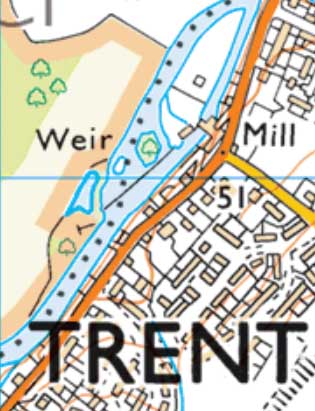

[ezcol_1half]Fifty-five minutes later, on the downstream ‘skirts of Burton, I hear the weir’s roar. In four summers on fast rivers I’ve never before encountered one unannounced by prominent signage heralding the perils ahead, and/or the means – a cut with one or more locks – of their avoidance.

No such warning was given here. Look at the map, river flowing SW to NE. You may think I can avoid the weir – diagonal black line – by keeping right and passing the mill to rejoin the main current two hundred yards below.

Look again. [/ezcol_1half] [ezcol_1half_end] [/ezcol_1half_end].

[/ezcol_1half_end].

*

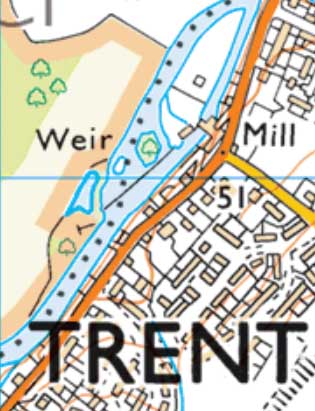

I’d left Steel City House on Tuesday at 09:30 (earlier would entail painful parting with cash on the bus). Rucksack on my back and heavier than I’d care for on a walking trip; canoe deflated, rolled and strapped to a collapsible trolley, I was at the bus stop in time for the 09:36 SkyLink to Long Eaton. There I took the 09:50 Indigo to Derby, then the 11:00 X38 to Burton and from Burton the No.12 at 12:05 for Lichfield, alighting forty minutes later at the Royal Oak in Kings Bromley, a pretty village on the Trent. The heat baked. The sky was azure. Whitewashed walls assaulted the retina. Shoulda brung shades.

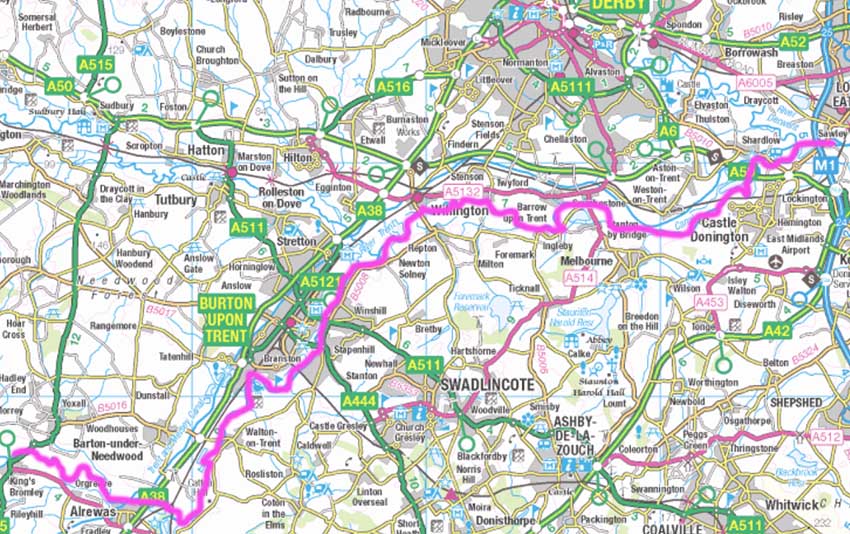

I’d done my homework. From the Royal Oak, a four minute walk got me to a layby on the Yoxall Road stretch of the A515. You can see it on the map below, a shade north of the church on the northern edge of King’s Bromley, as a white bracket clipped to the A515 running north east out of the village. It’s so close to the river that, even if the land is private, any trespass will be short lived. I can inflate boat on layby, manfully traverse any barrier, and be afloat in the few minutes it will take self and kit to cover a ten metre strip of pasture with cow pats and nettles aplenty – and me in shorts and sandals – to push out and get waterborne.

How can I be sure? Google Maps, satellite view, studied the night before, had told me so. Here you see river, road and, sandwiched between, a stretch of that long layby.

It feels like cheating.

The land is indeed private, grazed by a dairy herd. It’s so hot the cows are huddled under trees a few yards upstream and left of pic below. They won’t give me any grief. And the ease of access is almost embarrassing. No barbed wire. No vicious thorn hedge. Just a fence easier on leg and hip than the average Peak District stile, then the aforementioned nettles and cowshit …

… neither of which I avoid but since when did such pleasures as I’m about to experience come at zero cost? Besmirched left foot and sandal are rinsed in the Trent, stung legs soothed with juice of vigorously rubbed dock leaf.

I’m afloat at 13:26. Just look at that water. Within minutes I spot a brace of fish, each a foot long. The forked caudal fins rule out trout, the cigar shaped bodies perch. That leaves roach or rudd – consistent with the red tint to the pectoral fins – but the prominent mesh of scales says chub.

With next to no rain for weeks past, the river is low. In the first few hundred yards I have to get out twice, three metre painter over shoulder, to tow the boat downstream over pebbles and a scant three inches of water. Give me five, and a fully inflated floor chamber, and I can stay on board. Three’s too big an ask.

Not for the first time I sense some guardian angel looking out for me. I’d mooted a put-in at Weston, a good fifteen miles upstream of King’s B. But with only one and a half days to do this trip – I’d a walk planned with a mate on Thursday – I knew I’d never be home by Wednesday evening or even, at a push, early on Thursday morning.

Just as well. Eventually I want to canoe as much of the Trent as humanly possible. Realistically, that means as high as the downstream outskirts of Stoke, doable after heavy rain. Next spring perhaps, but not now. Not if I had a fortnight to make the trip. 1

Thanks to top-up feeders like this …

… the river is soon bigger and deeper.

Youthful high spirits.

I’m about to make a mistake. This boom, and the roar below it, tell of a weir ahead. Not the one I opened with, and will return to in due c. But a weir all the same. As usual, there’s a canal cut to the left. Assuming it will be short, and end in a lock that will return me to the Trent, I turn into it.

A quarter mile along, with no lock in sight, I spy this affable dude. He lets me take his picture …

… and in the ensuing conversation tells me this is no short cut but a spur on the Trent & Mersey Canal. If I continue I’ll be going further and further from the Trent. He’s wrong as it happens, but I don’t know that and it’ll prove a fortuitous error.

Back to the weir. Reassess. Looking in turn from each end of the boom I learn two things. One is that both banks downstream are a wasteland of thorn, nettle and dense scrub. No way through, least of all for Beach Clad Man toting camping kit plus trolley and 3.3 metres/15kg of inflated canoe. To cap it all, there’s ne’er a point of re-entry to be seen. The only way down is afloat.

The other thing I learn, from this angle at the left extremity of the boom and standing up on the canoe while steadying myself on one of those huge drums …

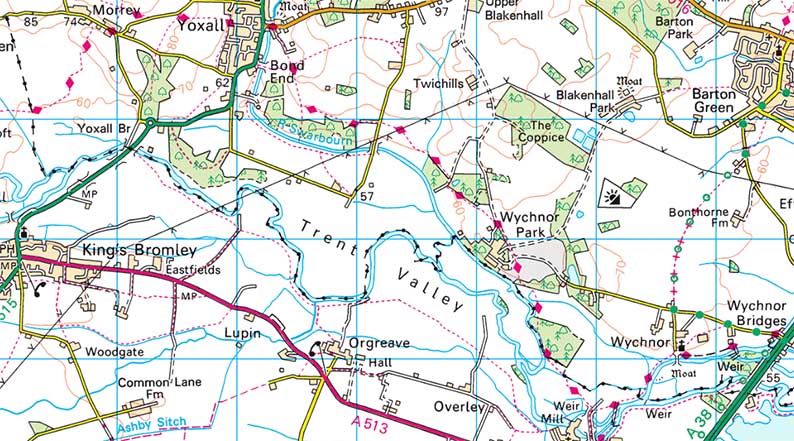

… is that the weir is four metres from lip to foot, angled at roughly thirty degrees. I’ve never shot one this big, let alone while laden with camping kit. I consult the 1:25000 OS map on my Galaxy S7. It seems my man was right – but that’s only because I don’t pan across to take in the bigger picture while maintaining that info-packed 1:25000 scale.

(Back home, looking at the same section of map on a big screen, I’ll discover that the cut would have led me back to the Trent after all, though it would likely have taken an hour or more.)

But the way things look right now, I’m not spoiled for choice. Fuck it: you only live once. A cool thing about inflatables is you can cram stuff in tight. I pummel the rucksack down and forward into the air pressurised grip of the bow, then drive in the collapsed trolley, only an inch wide sideways on, as a wedge. I do similar with the dry-sacked gear at the stern. I then paddle to the right bank to glide over two sunken metres of chain, noted on first arrival, that give the boom flexibility in conditions of fluctuating fluctuation.

The water immediately downstream is slack. There’s always a hefty safety margin twixt boom and lip of weir. I do a final kit check – nothing loose – and remind myself there’s no acceptable alternative. Four paddle strokes and I hit the point of no return.

Much ado about nothing! I’ve had scarier rides on the log flume at Gulliver’s Kingdom when the kids were little. As I slide over, I’m into the turbulence below the weir without so much as a drop coming aboard. I sense, mixed in with the elation, remorse and mourning for countless similar weirs hitherto funked.

Mere seconds after the epiphanic moment.

Climb every mountain!

Ford every stream!!

Shoot every weir!!!

In a gloomy patch where trees crowd the water, I spy this chilling reminder of those in peril on the Trent.

That a vessel this big could have gotten so far up shows how variable the flow can be. The river must have been in spate at the time. Not until I’m near journey’s end, thirty miles downstream where Derwent meets Trent, will I see another boat of this size.

I see many birds. Countless herons and their recently arrived cousins, little egrets. Twenty years ago you never saw the latter in Britain. Now they’ve become common, but in a narrower range of habitat. I see grey herons on all stretches, fast or sluggish, but egrets only where fast runs beget shingle bars. Since such bars afford easy get-out, I’ve learned to anticipate them as much as two hundred metres upstream on straight runs. Where I see that brilliant white, smaller than a swan and markedly different in profile, there’s a high likelihood I’ll soon get to stretch a leg, take a leak or even brew up.

I’ve patented this water cooling system.

Cormorants are less plentiful but over the two days I count two to three dozen. Though divers, rather than wading predators, they don’t need the same depth of water as the crested grebes. Lower down the Trent you’ll see the latter from time to time but even at Beeston and below they prefer the deeper water of the many flooded quarries close by.

Three times I see a kingfisher. Sand martins still take flight from nest holes in banks like this …

… though not in the numbers seen in early and mid summer.

This is the golden hour, early to mid evening.

And now I really need to be looking for an overnight resting place. I’ll soon be in Burton.

The right bank, looking downstream, has a few muddy beaches overhung by trailing willows, dark and uninviting. On the left bank I see a golf course but the light is draining from the sky, leaving only a few dog walkers still about. They’ll be gone soon enough.

It’s now dark though you wouldn’t know it from this shot. (The phonecam auto settings I opt for when afloat have overcompensated.) That WW2 ‘pill box’ machine gunnery will shield me from the casual eye in the unlikely event someone passes. Its entrance sealed in concrete long ago, it doesn’t stink of toilet. Between it and the river I find level ground for my canoe-turned-cot.

I sleep well on my air bed. I’ve yet to test this but feel certain that pneumatic mattress will give overnight comfort on the shingle bars I’m so fond of. (Checking first that there’s no prospect of rain. With all those moorland feeder streams to the north, the Trent is a classic flash-flood river.)

As previously noted, I’m putting back in by 06:20 on Wednesday.

[ezcol_1half]Fifty-five minutes later, also as advised earlier, I’m at the pesky weir I began with. Here’s that map again. The diagonal line marks the weir. The mill appears to block off the alternative route to the right.

Hugging the right bank to stay clear of the lip, I paddle to the mill to assess the sitch. It’s not good. The water which didn’t crash over the weir is about to pass through the sluice gate shown in the next image, to pursue a subterranean course below the mill.

Add to this the fact three sides of my gloomy cul-de-sac rise sheer from the dark and deep, with scant concession to the intrepid paddler, and again my options seem painfully few.[/ezcol_1half] [ezcol_1half_end] [/ezcol_1half_end]

[/ezcol_1half_end]

What did I say about fording every stream and shooting every weir? From the mill end, the first twenty yards of weir are almost dry. I can park the boat on the stones at the top and get out for a long hard stare.

Carefully does it. I might easily take a tumble, in my crocs on these slimy stones. For one mad moment I wonder if I could lower canoe and kit down this near section – besides three metres of painter permanently tied to the bow, I have another five on board – then slither down after it. Two cold realities restore a semblance of sanity. One, I hit saucy sixty-nine come Michaelmas. Two, the water below looks ominously still. My reward for all that risk and endeavour could be to find myself marooned on a jungled islet with no way downstream.

So why not shoot the weir, buoyed by my triumph of yesterday? Again two things. One, this is steeper than the weir shot in the handsome manner described, its decline convex rather than a straight diagonal – suggesting an airborne component to the vectorial equation. Two, behold the jagged rocks below, bearing in mind that the water immediately under the drop becomes visible only after you’ve passed the point of no return and rendered unto gravity that which is gravity’s.

I’ve one last avenue of enquiry before I give up, paddle back upriver and find a canal bypass I hadn’t noticed on the way down (highly unlikely: a negation I’ll later confirm cartographically) else quit to slink home by bus. This last ray of hope requires going back to that dead end at the mill. With all my kit I won’t easily scale that hulking sluice gate. And those sheer walls on either side are a non starter. But what about here, a corner of deep water that’s dodged both weir and sluice?

How do I know it’s deep? It’s not like I’m gonna dive in and find out. But look how stagnant the surface is, yet I hear a muted roar below these rusted cogs and defunct transmission system. A second man-made underground water course must run two fathoms down, a vortex so deeply submerged as to leave the surface a scum coated stillness.

This ghostly structure, at right angles to main mill and sluice gate, once drove a second wheel. In George Eliot’s day – her Floss was this very river, albeit fifty miles down – it must have been a hive of industry. Now it emanates an eerie quiet.

Had that platform of meshed cast iron been an inch higher, or the water an inch lower, I could have wedged the canoe in for a stable get-out. As it is, I must proceed with icily attentive care.

(Would you relish an inadvertent plunge – or even dropping some vital piece of kit – in this dank tank? With its hidden and potentially lethal undertow?)

You’ll be happy to know I make it, though it’s my sad duty to report that several large spiders are rendered homeless in the process. My thoughts are with them and their loved ones at this difficult time.

I’m expecting an irate home owner to come out and tell me to get lost. No one comes, though most of the mill complex is now flats at the posh end of salubrious.

I need a re-entry point.

The water gods are smiling on me after all. A mere thirty yards away, most of them on mown grass where I can drag the boat instead of carrying it, I find the very spot.

I’ll be on my way then. Oh, did I just see someone come out of a particularly attractive flat? She looks friendly. I’ll ask if she’ll fill my two empty water bottles. She is and will. Now I can make coffee, in the warm but not yet blistering sun, at a picnic table on a communal lawn between main river, and the stream emerging from its passage beneath the mill.

Idyllic. Now I really will be on my way, caffeine running its own course through the bloodstream to kick start the morning. I feel like Hawkeye without the Mohican.

Stretches like this next one are divine. Plenty of juice in the current to sweep you down, but no tricky bits to interpret: no danger of being beached in the shallows, and no willowy overhangs to deliver a fatal KO …

… just a few overheating kine, seeking cooling immersion though its barely nine-thirty. Can’t see ’em shifting out of my way. Evasive action is in order.

At this point Repton School, established 1557, is a mile to my right. Later I’ll learn that the river entering two miles upstream on the left was the Dove. Of Isaac Walton and Charles Cotton fame. Its upper reaches, around Hartington and Ilam, are familiar to me from many a day hike, and one or two camping trips.

At ten-twenty I get my first sighting of the five cooling towers of Willington coal-fired: disused and part demolished. Such are the loops and snaking bends of this great river, it’ll be twelve-thirty by the time I see the last of them …

… not that I’m complaining. I revere their majestic forms, visible for miles in every direction on these vast flatlands of flood plain …

… though every now and then …

… the ground rises in a most delightful way.

A tricky stretch. Not dangerously so. No swirling depths below willows that can knock you out and leave you to drown, trapped in a tangle of submerged branches. But on these reaches it’s easy to misread the current, especially when tired – and I’ve been on the water several hours without let up – to find yourself on the rocks.

It’s now close to five o’clock. It’ll be dark by eight and I’ve many miles to travel. I’d hoped to get as far as Beeston for a walk home. But Sawley, a mile down from the Derwent’s entry south of Derby, will do. I’ve canoed in separate trips from there all the way down to Newark so my goal of paddling the entire length of the Trent in (not necessarily contiguous) stages will have taken a major step forward if I reach Sawley by nightfall.

I recognise this bridge. It’s a stone’s throw upstream of the Derwent’s entry, placing me a scant mile from Sawley. That’s just as well. It’s five past seven and I’m dead beat.

Still on the Trent – left is upstream – and looking straight up the Derwent ten miles southeast of Derby. See the sign, left edge of picture? It marks the Trent & Mersey Canal. This is a three way junction.

I phone home to let Jackie know my whereabouts. She offers to pick me up at Sawley Marina. I snatch her hand off. I’m french-lacquered from fourteen hours on the water, less a few breaks that wouldn’t add up to an hour. She’ll set off in five. With Sawley twenty minutes from Steel City House, she should arrive around the time I do.

Ten minutes later I’m about to pass under the M1, a few minutes from journey’s end.

About to dock. It’s been quite a ride but …

… a fabulous trip. So many stories untold, pictures unshown. But this post has gone on long enough. Thanks for staying with me.

* * *

- Update 2/10/21. My remarks on there being insufficient depth, upstream of King’s Bromley, until we’ve had heavy rain were shamefully defeatist. See my report of a trip two weeks later, from Salt to King’s Bromley.

Wonderful to read this. Seems like you had a fantastic, beautiful and adventurous trip.

Hi Dineke. My trip was all you say and more. One thing I didn’t mention is that, between the hard slog of sluggish stretches where you really have to work, and the intensity of dangerous runs where you have to give undivided attention – plus of course the many practical problems to overcome – are countless moments of spontaneous meditation; of incredible depth and stillness.

Great account Phil and, as ever, fascinating / beautiful pics. Thanks for making it home in time for a stroll with me the following day.

Walking with you was perfect Bryan. Physically I got home dead beat on Wednesday night, but the muscles for walking are so very different that our gentle ramble was the ideal antidote. And of course, as always, the conversation was great – and that too balanced my two days of near solitude on the water.

Aaah Phil, what a pleasure to start my Saturday on the “stoep” ( Afrikaans for verandah!) with my first cup of coffee, the Geese slowly coming in from Siberia for our “mild” winter, and the luxury to enjoy your little adventure in word, and as ever embelished with wonderful pics.

Hope the rest of your trip is an enjoyable experience, allowing you to come back and write about all the shite that very few people are prepared to do, but we poor sheeple would never know about, without the likes of people like yourself.

All the very best from the North of germany on the banks of the Ems river.

Cheers,

Billy

Thanks Billy. When I’m afloat on trips like this, all the poisonous aspects of our corrupt world fall away; melted by the beauty of nature and my immersion in it.

All the best to you too.

Beautifully presented Phil. You have the skills and wit to produce a trip that could rival passage to India or a trip up the Nile. Made me feel I was alongside an able-bodied inland sailor. Xx

Why don’t you and me take a trip up the Nile, Jim? On second thoughts, given how much water has flowed under the bridge since our Firparnian days, maybe we should make that down the Nile.

As it happens, when I was negotiating those bathing cows, it occurred to me how benign a country Britain is. Imagine being in an inflatable canoe on the Limpopo and rounding a bend to find a herd of hippos straight ahead!

Even Sinatra’s egrets make a short re-appearance… wonderful stuff!

Thanks wov! I think you refer to my post of twenty-six months ago – Egrets, I’ve seen a few …

Really enjoyed your Trent adventure Phil, thanks.

I know that part of the country well from my days as a young teacher in Derby. It was in the late 70s and I usually worked the summer holidays driving an ice cream van for Frank’s Ices. My patch was from Alvaston, where I lived, all the way across to Long Eaton. My best sales were in the car parks of pubs by the river/canal near Sawley… until I got busted by a landlord calling the police on me… I didn’t know he had an ice cream cafe on the towpath while I was flogging Frank’s best vanilla in his car park.

There was something deeply sad and lonely about pulling up in a rain-lashed street in August, ringing your tune… and watching bugger all happen. Plus, I was always selected to cover other sellers’ patches when they were off to enjoy the massive static sales of the Monsters of Rock at Donnington.

Still, I got to eat as many flakes as I liked and to give free ice cream to my little sons and their mates. As always, good to read both your thought-provoking take on, and your lighter interludes from, life. Keep up the good work.

Hey Keith – good to hear from you, and ta for the personal account of your own life and times in a part of the world I only discovered three years ago. Now I’m seen from time to time, a pair of woofers in tow, pacing the decking at Sawley Marina else the streets and mills of atmospheric Long Eaton. (As late as the 70s some of those lace mills would have been operating. Had I more time I’d love to research its history.)

In boyhood the middle stretches of the Trent were more familiar. If I was really lucky, dad or my elder half bro would take me on a chara trip to fish at venues like North Muskham, Fiskerton and Laneham Bridge. I remember cold mornings before first light, waiting in barely containable excitement for the chara to turn off Halifax Road and into a pub car park at Wadsley Bridge while men in donkey jackets smoked and jested and bragged and used words that’d fetch me a clout round the ear or worse.

Having now paddled from King’s Bromley all the way down to Newark, I’ve two slices of unfinished business. The stretch from Stoke down to King’s B will present problems of insufficient depth. From Newark to Cromwell Lock should be plain paddling but from thereon down the river is tidal: an element I’ll need to factor in. On the one hand I don’t want to paddle against an incoming tide. On the other, as the tide ebbs, those muddy sides – Lorna Doone lethal and what a way to go! – can be up to twenty yards on both banks, and slanting at 45 degrees into the river to make casual egress out of the Q.

Food for thought.

Watch this space – and stay well in Cyprus.

PS – you’re lucky to be alive. Every now and then you hear of rival operators pulling guns on one another, in hot weather, as ice cream van turf wars erupt …

It is just possible that, amongst those donkey jackets, were my mother’s younger brothers, Uncle Alan and Uncle Brian, who lived just up the road from Wadsley Bridge, on Parson Cross. They were frequently known to disappear at daft-o’-clock with their fishing baskets and a pint o’ maggots.

As for ice cream wars, Frank’s real name was Franco. I think they came to Derby from Sicily…

I expect Frank made the kind of offers you couldn’t refuse but, as all of us sooner or later must, now sleeps with the fishes.

Ah – Alan and Brian. I remember them well. The very duo I’d hear at daft o’clock – great expression, btw – engaged in pescatorial one-upmanship …