A five minute walk from my door gets me to Beeston Station, where in Wednesday’s bright sunshine Jasper and I took the 09:25 to Matlock by way of Long Eaton, Derby and the Amber Valley halts of Duffield, Belper, Ambergate, Whatstandwell, Cromford and Matlock Bath.

The Amber rises at Clay Cross and flows south to Ambergate, where it tops up the Derwent. I want to start my kayak camping 2019 by following the latter from its source below Ladybower, through Bamford and Hathersage, Grindleford and Calver, Baslow and Chatsworth.

Strictly speaking the source of the Derwent is Bleaklow. Rising unpropitiously from the peat and windswept heather of the Peak District’s wildest plateau, it runs four miles southerly to Slippery Stones, where a younger me took a skinny dip or two with a sweetheart or two, but never at the same time. Flowing over gritstone slabs, which in hot summers strip the icy chill from pools ten feet deep, it passes beneath the beautifully proportioned packhorse bridge, built from kingsize blocks of that same gritstone to serve medieval peddlers plying the wares of Penistone and the north to delight and fleece Hope Valley lowlanders. A mile downstream these beery currents of foam-topped black and tan are lost in a Howden Reservoir separated from its Ladybower sister by a dam wall of cathedral design and dimensions.

(This, and Howden’s watery expanse, served in practice runs for Operation Chastise‘s tactically brilliant but strategically ineffectual bouncing bomb raids on the Möhne and Eder Dams in the summer of 1943. The 1955 film Dambusters – a 2001 edit dubbing the name of Richard Todd’s black labrador from ‘Nigger’, after 617 Squadron’s canine mascot, to ‘Trigger’ – gave the raids an iconi status mere truths cannot subvert. A few times on Derwent Edge, the most northerly and dramatic of the gritstone edges formed when glaciers scoured out what is now Derwent Valley, I’ve found myself looking down on a lovingly restored Lancaster cruising a hundred feet above Howden and making for the lip of the dam for Old Times’ Sake.)

In practice though, certainly for my purposes – since I’d be a sitting duck for irate officialdom, kitted up to the nines in my black and yellow Sevylor Colorado atop Sheffield’s premier water supply – the start of the Derwent is taken to be directly below the embankment at the southern end of Ladybower, its gentle grassed over slope a far cry from Howden’s near vertical drop.

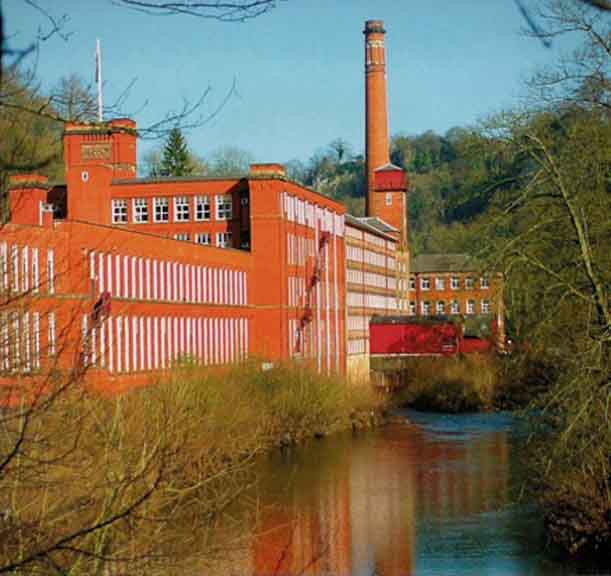

At Rowsley, a mile or two south of Chatsworth Park, the peatily acidic Derwent is joined by the lusher, limestone alkalinity of the Wye. I’ll paddle through Darley Dale, Matlock and the railway towns I opened with: towns wedged, like Matlock Bath, into narrow clefts that thread between precipitous gorges, else sedately ascending valley sides of broader sweep and lesser gradient at Matlock and Belper; towns watered by moorland cloughs that splash on down between and below stone cottages and twee cobbled squares to the river; its brick stacks, soot blackened all their working lives, now grit-blasted to a red they never knew, smoking a habit kicked long ago. Those cotton mills of Georgian neoclassicity now serve other purposes – malls, museums and apartments for the up and coming – or none at all. They speak to a Britain gathering steam for its role as workshop to a world served in the first instance by canal and rail (both redeemed by nostalgia and tourism to stand as gritty icons for a landscape scarred but austerely handsome); in the second by sea lanes policed by the Royal Navy.

The Derwent, with Ladybower, Howden and those few miles of moorland stream excluded, is fifty miles. I estimate four days of relaxed paddling. I need a window of acceptable weather – I’m no Bear Grylls – but this has to be balanced against the fact that the earlier I do it, the fewer altercations I’ll have with fly-fisherfolk and bailiffs. This is a legal grey area: does ownership of river bed and bank confer ownership of the water itself? On the rare occasions the question has been tested, judgments have gone either way, with no precedent assumed. Watch this space.

Twelve days before the Matlock ramble whose pictures I’ll get to in due c, I walked with my pal Mark. We’d headed for the tops with Baslow, Curbar and Froggat Edges in mind but, with wind outrageous and conversation difficult to impossible, dropped early to Calver to pick up the east bank of a Derwent in spate after days of rain. A scare had me put Jasper on the lead. He’s not ditzy but his falling in didn’t bear thinking about. I’d not get him out easily and maybe drown in the trying. Many have. I won’t canoe in such conditions. Shooting weirs, suitably equipped and without luggage, is one thing – though even then I’d want more experience under my belt – but paddling these waters in a canoe laden with kit is off limits. Even in calmer conditions I’ll need to portage around the likes of this, a mile upstream of Calver.

But forward to Wednesday. On that train to Matlock I spread my down jacket over the table in the sparsely populated carriage for Jasper to sit on. He likes trains more – or dislikes them less – when he can see what’s going on. I wondered if I’d get grief from the conductor but, not a bit of it, she stroked him every time she passed. With the woofer more or less content, I put the few inches and fewer ounces of glass and metal that do me for phone calls – plus photos, OS 1:25k mapping, music, video, emailing, browsing and blogging – into retail therapy mode to order a well recommended Highlander Hawk bivvy bag. It came next day. At 950gm it’s half the weight of my tent though, in canoe rather than on foot, that’s not the point. In a bivvy bag I can sleep in tighter spaces – under a bridge, say, or upturned canoe – than the smallest tent would allow. That’s all to the good when, as reported apropos my adventures on the Wye last summer, wild camping ain’t always easy, not with pitch options reduced to the few yards from the bank I can feasibly drag kayak and contents.

At 10:30 we alighted to walk down the road to cross the Derwent into Matlock town centre, and head for the cafe in the park. I ordered a double egg bap and latte with extra shot, insisting the bap came first: coffee is for after the meal, not with or – perish the thought – before it. The lass taking my order was sniffy about that but the older lady bringing them to my outside table, in the desired sequence, did so with a smile. At 11:00 Sue joined me, having bussed from Sheffield for free with her senior pass. I’d forked out £6.65, down from a tenner due to senior rail card.

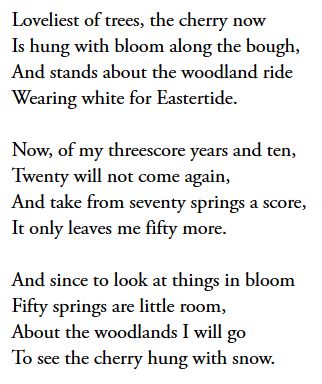

The three of us took the Derwent’s east bank downstream through the park but soon began to climb. Mostly the river remained in sight: at times from afar, across woods and meadows that descend in no great hurry to the valley floor; at other times from vertiginous limestone crags plunging hundreds of feet to the same. The sun stayed with us all day, warming fields of vivid green and startling yellow. Birds sang, hedgerows bloomed. In the live-forever (when you’ve done a line or two) years of a distant past I let so many of these days of early spring pass me by, lost in the blinking of an eye to all manner of indolent vice or, worse, urgent banality. Now I intend, like Housman’s blue remembered youth, to savour those of the years left to me.

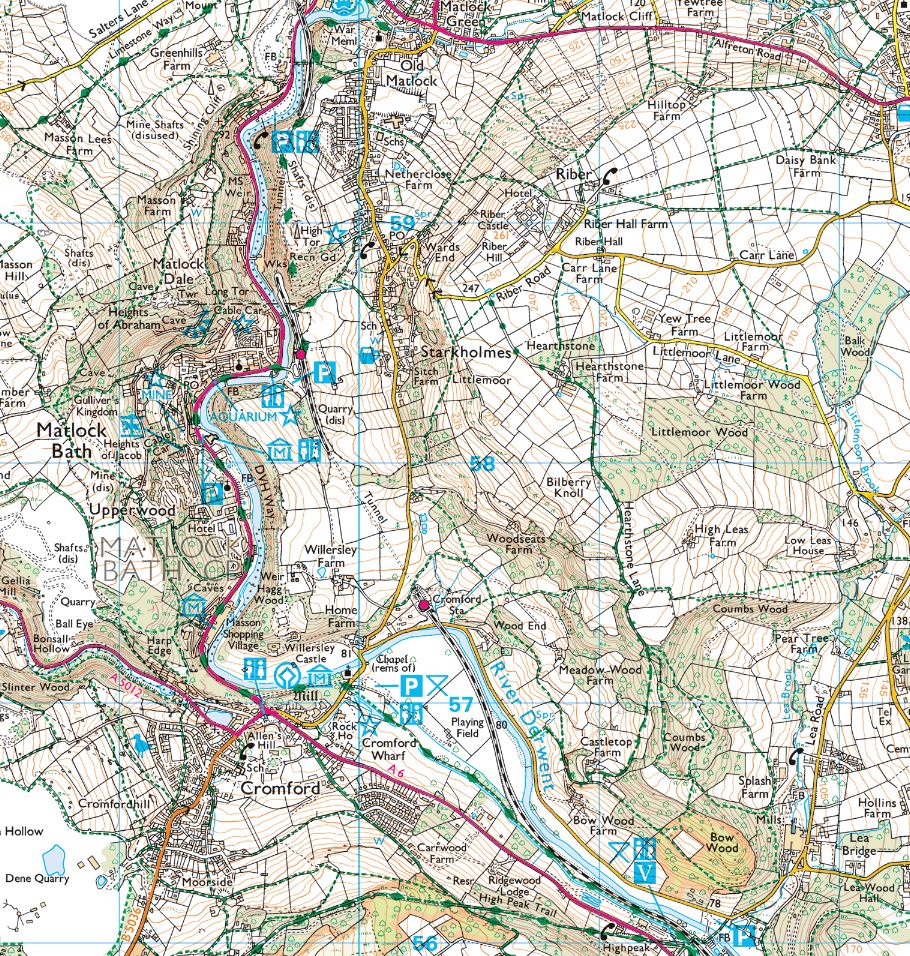

Here’s the area we walked, mostly north to south and close to the Derwent, with Lea Bridge – tucked into the lower right corner – our furthest point east.

Four hours after leaving that park cafe we came to a Cromford Canal that once linked Richard Arkwright’s mill to Erewash Canal and hence the arterial Trent. At this meeting of many ways we encountered motley groups: a guided tour at the mercy of an industrial heritage pedant and trying to look interested, a solitary fellow hiker or two and a middle aged couple, aided by their dog, dragging the canal with hefty cylindrical magnets attached to lengths of blue nylon rope. Sue asked if they ever find mobile phones. You bet they do.

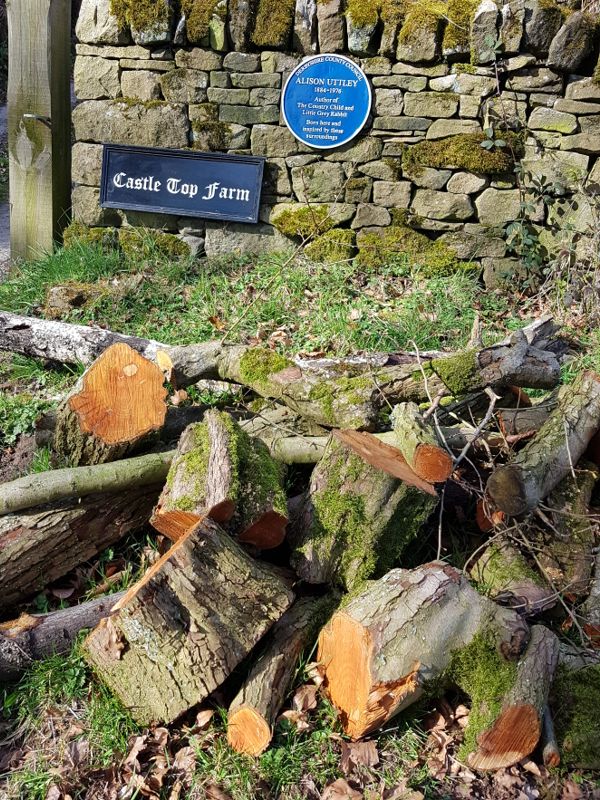

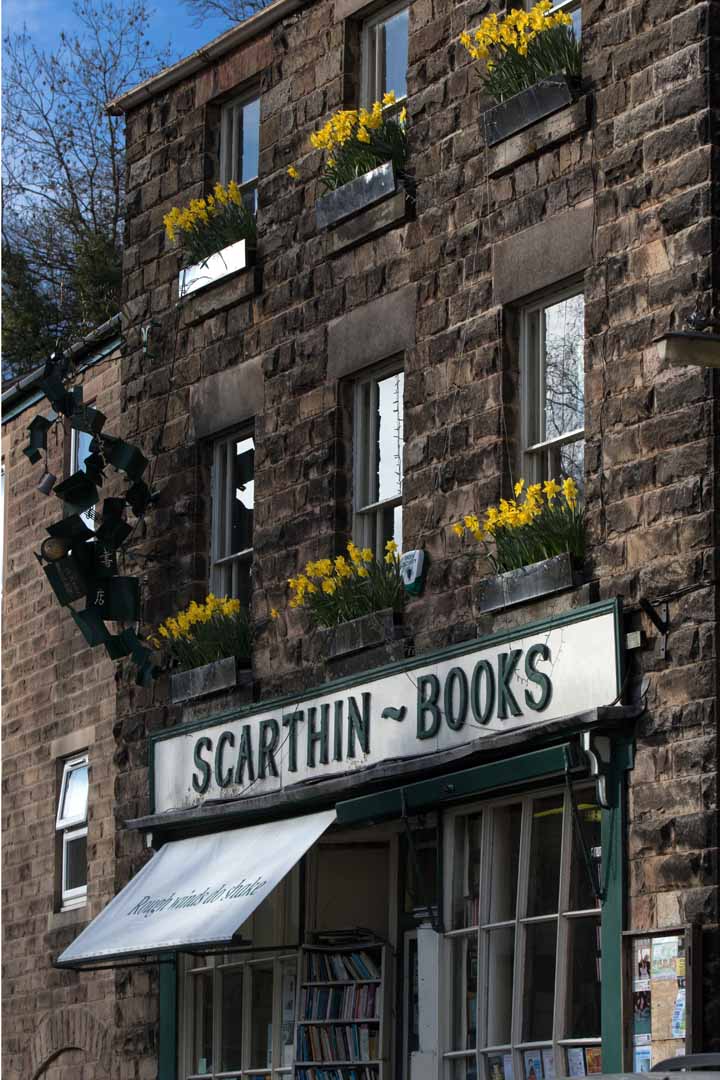

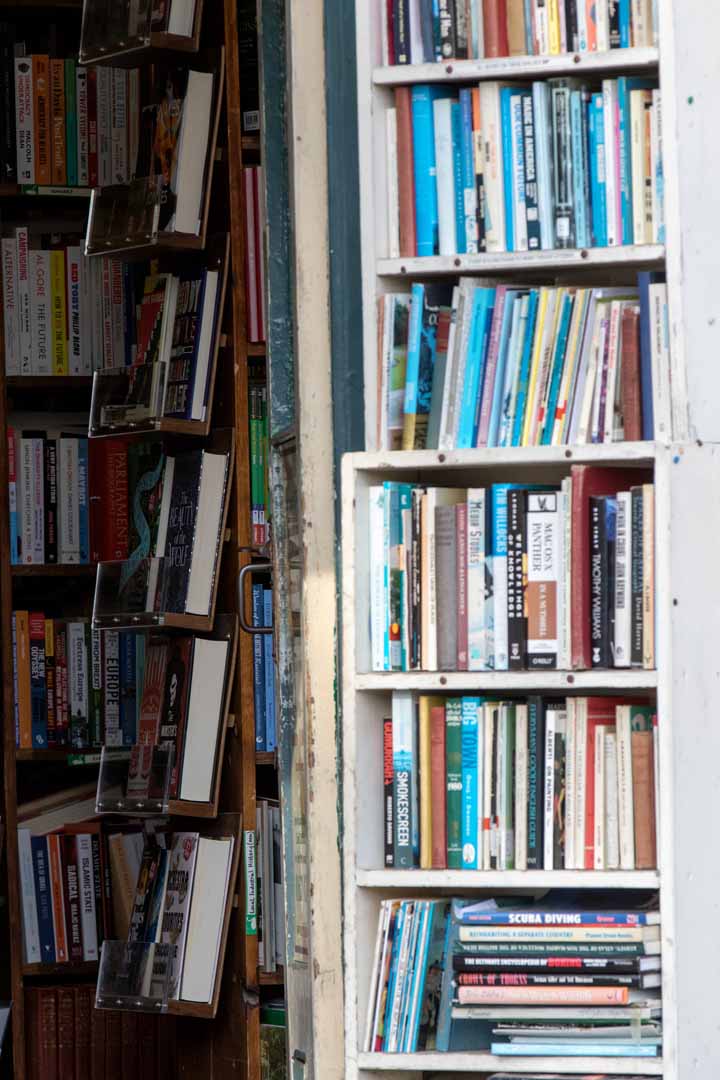

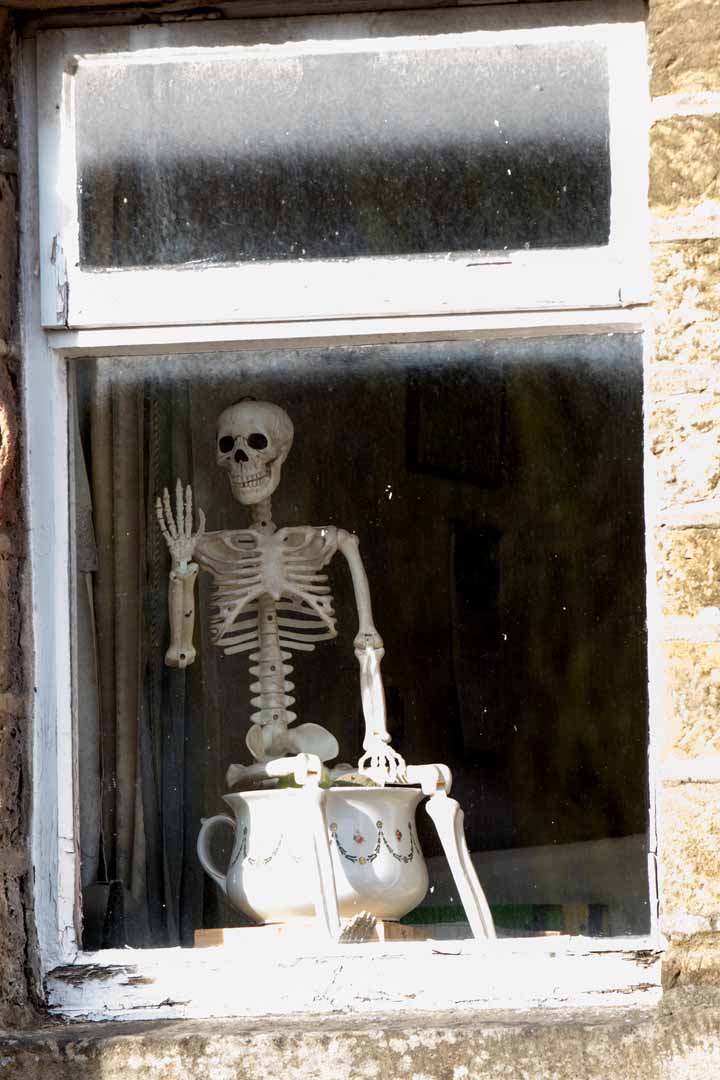

After a few hundred yards the canal took us to the wharfe. From there we hiked into Cromford, home to the world’s second best second hand bookstore. (Alnwick’s beats it on capacity and matches it on location but it’s still a wonderful place to hang out, full of quirks and frequented by the kinds of eccentric only the fusty odour of ancient tomes can draw.) Its book lined floors lead by way of creaking flights to a pretty cafe with outdoor, flower-and-chimney-pot terrace. Dogs are allowed in the shop but not that cafe. No problem. With the sun still strong we took Sue’s tea and my coffee across the narrow lane to carved wooden seats made in Narnia, and there did gaze on daffodil lined banks fringing the town’s tranquil dam – another eighteenth century legacy – where swans glide and coots forage.

After which we took the bus to Matlock, FoC. (“No, but thanks for asking”, said the driver to my wondering if I had to pay for Jasper.) A perfect day. Thanks Sue. Next time you read me on the subject of the Derwent, I’ll have taken, or be in the midst of taking, my canoe from Ladybower outfall, all the way south of Derby and a shade west of Long Eaton to a date with the Trent and there on down to the pontoon at Beeston Marina. There I’ll deflate the dreadnought, strap it to my collapsible trolley, shoulder my rucsack and be home in ten.

Meanwhile, a few snaps from the Wednesday-with-Sue archive.

I’ll say tara then.

* * *

I wish I could still hike. Years ago I could have and did, but no more for me. Lovely to see so much from the comfort of my sofa with Grace snoozing beside me. Greyhounds, even xbreds like Gracie, don’t trek that well, despite dragging me around for two hours on even ground, her stick like legs don’t do banks and rock falls. The pictures were excellent, you have a good eye and skill with a camera. Hope to see more.

I hope to supply more, Susan, soon as I take the trip!

Arkwright, an interesting character. Certainly a pioneer in the organisation of industrial exploitation and the shrewd user of a constant source of water power courtesy of the sough from a local leadmine. Blokes worked in the mine, the rest of the family in the mill. Apparently he wasn’t a bad employer – for that era!

His competitive edge was based on his adaption of existing designs for a water frame to spin wool faster and in larger quantities than the previous cottage based industry using the foot powered spinning Jenny. He patterned his improvements and charged extortionate amounts to others to replicate his design. He spent the following 20 years in constant legal battles with the original designers ( and one time partners) over pattern rights – which he eventually lost – but not before making a factory load of money.

Fascinating, Bryan. There were a good few ‘model employers’ at the dawn of industrial capitalism, Owen and Wedgewood among them. I don’t put it all down to enlightened self interest. Some, I think, arises from the greater latitude afforded by commodity production not quite fully generalised. With the law of value not completely operant, the ruthless logic of capital accumulation had yet to reveal its totality. Successful mill owners with a conscience had some leeway to indulge it.

Ta for raising the patent issues. The rich and powerful could and still can win the war after losing every courtroom battle, though in the main they do so by threatening to bury litigants with right on their side, maybe, but not limitless finances.

I associate Arkwright with cotton but it doesn’t surprise me to hear he was in wool too. You gotta admit, though they were early riders of a mode of wealth production whose dynamic now stands to nuke or bake us, these dudes were impressive!

Mind the weirs at Belper and Milford, Phil. And call if you need a quick coffee!

Timely, Cal. I’m this minute tracing the route using Google Maps in Satellite mode. I count sixteen weirs between Yorkshire Bridge and the Trent, of which Belper and Matlock Massons look the scariest. But as long as it’s daylight, and I’m not fast asleep, there’s little danger of inadvertently crashing over one. Bigger issue is ease or otherwise of getting out above and putting in below each weir. That’s compounded on a multi day trip with all the gear entailed. I’ll drive up this week to inspect them one by one. That sends the carbon footprint soaring of course …

I’ll take you up on the coffee. Be good to see you. Was thinking of you as I wrote this. Bet you recognise many if not all of the places photographed!

Patently woolly thinking! The perils of early morning commenting.

You are right Phil, Arkwright was a cotton man and although ‘patterns’ have a big place in industrial production I meant ‘patents’.

I hadn’t picked up on ‘patterns’ for ‘patents’ – guess I just read what I assumed you meant.

Can we be sure Arkwright, dyed in the wool entrepreneur, stuck with cotton?