Continued from part 3 …

On the road to Rishikesh/I was dreaming more or less/And the dream I had was real/And the dream I had was real …

John wrote those lines shortly before the Beatles, disillusioned by the Maharishi’s sexual antics, walked out on his Rishikesh ashram. (He’d later repurpose the tune for one of the best songs on his Imagine album, Jealous Guy.) For a graphic account of the Fab 4’s bust up with their giggling guru, try Albert Goldman’s Lives of John Lennon. That sizable tome is a stiletto job, yes, but an unusually insightful one; well researched, well written and not without its moments of grudging admiration for its subject.

As for how Jealous Guy’s plaintive melody line may have been lifted from or at least influenced by a tune heard on Indian instruments to relative scales markedly different from the absolute scales of the West, try classical composer Howard Goodall. His fifty minute Channel 4 tribute to the Liverpool 4 never flags, or fails to be eye opening for one like me, unversed in music’s rule based structures. It is linked at the end of my own tribute, The Fab Four: a very personal view.

But I must press on with the story of my own road to Rishikesh. Since one of several major life lessons encountered on that road was the importance of an impersonal perspective, even and perhaps especially on one’s own personal experience, you must draw your own conclusions as to how well I learned it.1

*

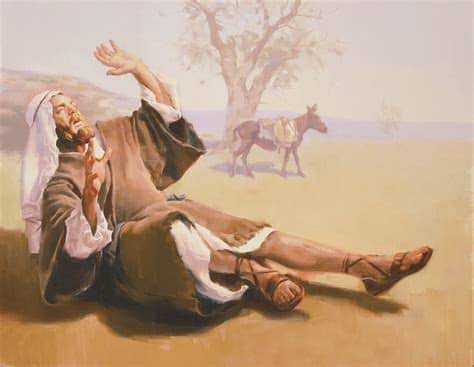

3. And as he journeyed, he came near Damascus: and suddenly there shined round about him a light from heaven. 4. And he fell to the earth, and heard a voice saying unto him, Saul, Saul, why persecutest thou me? 5. And he said, Who art thou, Lord? And the Lord said, I am Jesus whom thou persecutest: it is hard for thee to kick against the pricks.2 6. And he trembling and astonished said, Lord, what wilt thou have me to do? And the Lord said unto him, Arise, and go into the city, and it shall be told thee what thou must do. 7. And the men which journeyed with him stood speechless, hearing a voice, but seeing no man. 8. And Saul arose from the earth; and when his eyes were opened, he saw no man: but they led him by the hand, and brought him into Damascus. 9. And he was three days without sight, and neither did eat nor drink.

Acts 9:3-9 – King James Version

I don’t suppose the London School of Dentistry would strike many as textbook terrain for a quo vadis moment. By tradition, such lightning bolts strike in settings rich in dramatic ambience: the implied reproach of a spider’s tenacity in a dungeon, say, or a hammer blow from heaven in that epiphanic second before the grim reaper – in the shape of a charging bull, the undertow of a rip tide or a motorway collision – is cheated of his harvest.

Then again, maybe Saul-to-be-Paul’s road from Tarsus to Damascus was downright dull. Maybe, as he wended his way – his cloak housing a warrant to bust all and any Christians he could lay hands on – his mind was on the right of nations to self determination, on ruinous taxation, and on the state of Syria’s highways as his horse stumbled on yet another loose cobblestone.

Roman roads? Roman roads?!! What fucking roads?

Such unedifying trivia would be lost, and rightly so, in the edits of successive chroniclers, each with his axe to grind – if only that of not ruining a rollicking good yarn by piss poor handling of the atmospherics.3

Whatever. It was amid the unpropitious mundanity of the London School of Dentistry – held in the scissor grip of Whitechapel Road to the north, Commercial Road to the south, Aldgate Tube at the western fulcrum – I first heard my quiet quo vadis? There’d be louder ones later but with the gin clarity of hindsight I see that on this sunlit Saturday in late June ’96, as I slipped through those portals of tooth science for my day with Andrew Cohen, I’d reached my very own point of no return. That my passage to culthood still had five whole years to run does nothing to negate this. Inexorability is neither defined nor measured in units of time.

Ask the captain of the Titanic, with many hours – almost as many as it will take the nearest ship to reach the scene – to twiddle his thumbs and muse on inevitability. Ask the time management speaker Randy Pausch, a fitness fiend exuding rude health as he weaves top tactics for inbox management with deeper wisdoms and sparkling witticisms; all the while knowing his death to pancreatic cancer is months away, tops.

Ask the more pessimistic of climate scientists.

Am I playing fast and loose, through such examples, with the vital distinction between objective and subjective determinants? That’s the billion dollar question; one of ’em anyway. Am I laying it on a tad too thick? Maybe – my dear old gran did tell me a million times not to exaggerate – but I say a modicum of melodrama can be overlooked if the point lands.

*

I’ve likely given too big a build-up. This all too brief account of that day may seem anti-climactic. If so, bear in mind that I’m at the outer edge not just of my ability as a writer, but of experience itself. The matters I speak of are as infinitely subtle as they are powerful, and I fear I could write screeds on my recollections of this first real life encounter, and still leave you none the wiser as to why I look back on it as momentous. To those curious for more on his message, I suggest the bibiography at the end of part 3 – in particular the books by Andrew cited in the first paragraph – and to his website.4 To those curious for more on his charisma, I suggest any one of the three books – second paragraph of the same – by those who long ago rid themselves of its grip.5

My day at the London School of Dentistry was thrilling in ways I won’t even attempt to capture. I’ll just single out two things. One was his description – which I mistakenly attributed in part 3 to the audio tape, Meditation is a metaphor for enlightenment – of the enlightened relationship to mind, and hence to Life, as:

Like a conversation in the next room. You tune in when you need to but the rest of the time you ignore it. You’re grounded in a deeper place, where nothing ever happened and time and karma have not begun. As I speak to you now I’m in that place. In deep meditation, I know nothing: not even what I’m about to say next …6

Yet what he was about to say next proved always to be gob-smackingly immaculate, beyond the skills of any orator I’ve encountered before or since. As for the bit about tuning in and out of the movement of the mind on an as-and-when basis, for me this had an impact similar to that of Aldous Huxley’s accounts of his experiences with mescaline.

Man, I could use some of that!

And the other thing? Such was the intensity of straining to hear each word, such the intensity of each word’s impact on me, that when we broke for lunch I opted instead to exit the LSD (asking myself on the way out if the Acronym Scrutiny Team was on its annual Away Day when ‘London School of Dentistry’ was settled on7) and make for a nearby square, one of those small green oases London excels in. There I spent half an hour doing yoga. I needed space, physically and mentally, to order or at least calm my whirling thoughts.

Crossing the road on my way back in, I met Andrew doing the same in the opposite direction, flanked either side by one of the powerfully built men I’d seen in the morning teaching. Close behind – this seemed a protective formation, such as a head of state or mafia don might be afforded – strode a third. As our paths momentarily converged the teacher and I made direct eye contact.

It’s a cliché to say the effect on me was electrifying. So let me just say, since I’ve never minded a cliché if it gets the job done, that the effect on me was electrifying. In the darksome deep of his eyes and almost tortured set to his face, I saw the absence of pretence – too unfamiliar to me at that point to be recognised as such – I might expect of a condemned man taking his last steps to the gallows. Or a Christ on the ascent to Calvary, the insanities of the world held in the dead weight of a wooden cross he can scarcely carry. Shockingly human, the contrast of such piercing vulnerability with the wit, trenchancy – now playful, now caustic – and assuredness of the man who’d enthralled us all morning could not have been starker.

The moment passed, our different vectors carrying us off in opposing directions. I tried to shrug off an inexplicable sense of shock. I’m not immune to the effects of fame, or even a respected teacher’s authority. I recall the frisson – ridiculous but real – of mild excitement the day I locked eyes with Ricky Gervais in a bookshop on Charing Cross Road. Or that of Arthur Scargill giving a nod, the day we passed on a Sheffield street. I’ve noted too how friends in the acting world like to name-drop. Those who deny being awed by fame are usually fooling only themselves.

But this blast from the unknown was in a different league. It went way beyond star-struck and in any case Andrew Cohen was no celebrity in the ordinary sense of that word. It also lay orders of magnitude beyond my respect for even the best of the many teachers I’d had. My mind needed explanation, one it could encompass within its normal frames of reference, for the shock of that encounter, on the face of it unremarkable. To this end it did its level best:

I guess a guy like this must live in fear of some crazy, acting on Voices in his head, playing Mark Chapman to his John Lennon. A crazy who might just turn out to be me. Yeah, that must be it …

By the end of the afternoon I was telling myself something quite different – something I still, in spite of everything, believe far closer to the mark. What I’d seen was the face of a man standing not just naked, figuratively speaking, but without a skin. A man with none of the armour the rest of us have been wearing so long we no longer feel its protective but suffocating embrace.

Also by the end of the afternoon I’d signed up for an eight day retreat in early August, high up in the Swiss Alps with little to disrupt the pristine laboratory conditions for rare and singular focus on just one question.

Who am I?

*

The silence is extraordinary. Two hundred men and women sit in near total stillness: mostly on round, densely padded zafu cushions on carpets laid out across a floor of unplaned timber. So many of us, and in so small a space, yet the only sounds are birdsong, the whirring rattle of the grasshoppers and the tap-dance (as one man will later tell me as his measure of so exquisite a quiet, so acute a collective awareness) of spiders on the canvas above our heads. Every hundred years or so the bass note of the ferry on Lake Brienz is carried up the mountain side to reach us, 1100 metres above; its gently sorrowful monotone – the deepest conceivable Om – at one with our immersion in a void where nothing happens. Where nothing could happen, says The Man – who has removed all remaining doubt as to his right to speak this way – because time has not begun.

Otherwise, only the roaring silence of what some allude to as non dual consciousness; others as the call of the Absolute.

The meditation sessions are growing longer: an hour stretching to one and a half, then to two. Many of us return in the evening, when the day’s teachings are done. For hours on end we sit, immersed in a state I no longer pretend to understand, though once upon a time I thought I did.

On one occasion I stay all night in meditation, with no loss of focus next day. We have tasks of course. Though a cook is in command, we work in rotas to prepare meals, always to an exacting standard of taste and presentation,8 but otherwise have nothing to do but attend the teachings (taking part if so inclined in Q & A exchanges with The Man) and group meditations, and in the hours between throw ourselves, singly or in groups as we see fit, into investigating questions Andrew left us with at close of the previous teaching. Evening teachings begin with those who wish to speak taking the mike and reporting on where these acts of contemplation9 have taken them.

In such conditions, I discover, we need far less sleep than usual.

Mountains surround us on every side. Though a few rooms are available in the Retreat Centre, most of us are camping in an Alpine meadow ablaze with floral colour and alive with the sound of insects. The skies are an impossible blue and the days usually scorching, but we were warned in advance not only of the dangers of burning rays, but of mountain weather which can change mood in minutes. Never, we were told, should we leave an unattended tent unzipped. Thunder storms can strike at any moment. And so they have, to the cost of more than one camper who really should have known better.

Under the marquee, sides rolled down only where sun position dictates, we sit in shade while breezes carrying scents – oregano, meadowsweet and others unknown to me – play on faces and bared limbs with the lightness of touch of an assured and unusually attentive lover. Our days, and for many our nights too, are spent in states of consciousness I’ll for convenience call ‘non dual’.

So how does that work?

Says wiki, “ineffability is concerned with ideas that cannot or should not be expressed”. Which I guess lets me off the hook, but I’ll have a go anyway. Many have experienced, usually fleetingly, states of heightened awareness accompanied by an extraordinary sense that All Is One and All Is Well; of life suddenly making vast and immeasurably positive sense. These states lie beyond and are independent of those restless shifts of mood and circumstance which preoccupy us for almost every waking moment of our lives. (Then we die.) Their triggers may be hallucinogens, peak moments in sport, illness (think Juliana of Norwich) or nothing we can discern, far less repeat at will. Some are plunged into non dual consciousness as they wash dishes, drive home from work or walk down their drive.

Imagine these states extended over days. At one level you’re a normally functioning human being, acting in ways you have acted all your life. You turn up on time, conscientious soul that you are, when it’s your turn to peel carrots, lay out the zafus for the next teaching, or clean the shower block. But at the same time you are in a place where time and space do not hold sway. Nor does the incessant babble of the mind exert its customary grip. Even as you do those things all of us must, as our tax for being alive, you experience unprecedented lightness of being, its source a well of unfathomable mystery from which you are urged – conditions may never again be so conducive – to drink deep. (And to stay away from the phone!) In this extended vacation from mundane ‘reality’ things that normally matter a great deal have fallen away, while others you never gave thought to are now matters of cosmic significance since, if all is truly one, then you are the world.

As each thousand year day is followed by the next, the mystery deepens. Mostly you’re uplifted by a sense of extraordinary affirmation; sometimes you are gripped by terror …

… because there’s another way the acid parallel works. The full title of Huxley’s essay is not The Doors of Perception. It is The Doors of Perception: Heaven and Hell. At midpoint in these eight days came one whose rain fell not as ten minute cloudburst, promptly followed by those blue returning skies, but as all day downpour. Between teachings I put on waterproofs and made for a fall rendered the more dramatic for its waters being in spate. Alone on a rock overhang above the swollen pool at its foot, and in the grip of nameless fear, I threw a stick into the dark swirl.

Watched it tossed this way and that like a cork in a millrace.

This was my life I was watching, flung here and there by currents against which my tiny desires (what is fear if not desire doing a headstand?) gave neither independent propulsion nor reliable navigation. Andrew had warned us not to pay too much attention to the highs and lows of our emotions. Both, he said, will be amplified in these conditions. Our egoic selves will not take lying down the existential threat posed by the prospect of our own liberation having shifted from armchair abstraction and new age dinner talk to what he insisted – and I took him at his word on this – was a real possibility. These extraordinary states of consciousness could be my permanent abode, he said, adding only that I would have to want it above every other thing.

Think about that. Above every other thing.

I watched my stick carried here and there. When finally it reached its resting point on the scum flecked surface of slackwater near the tail of the pool, I headed back for the afternoon teaching.

* * *

Continued in Part 5

- An impersonal perspective on personal experience is still – whatever else I may have let slide or actively discarded from my time with Andrew Cohen – something I aspire to, if only in my writing. It informed the film reviews which got me into the blogging game fifteen years ago, and it informs the travel writings I’ve been producing for well over ten years. Most important, and in some future post I’ll share the ontology of this, it informed the reawakening after years of slumber of my political conscience.

- Yes, the KJV does say, ‘kick against the pricks’. ‘Ballocks’ has been around since 1300 but I guess that in James I days ‘prick’ did not mean ‘todger’ as well as (this being an ox-driving metaphor) ‘goad’. The double entendre is dodged in most translations by ending verse 3 at ‘thou persecutest’ / ‘you persecute’. Since I love the language of the KJV, and find that of later versions pallid and banal, I’ve gone with the former even if that does make me a bit of a stiff prick.

- Knee-jerk dismissal of Acts 9:3-9 is no more credible than insisting on its literal truth. All the world’s major extant religions came towards the end of a neolithic era ushered in by the advent, 10-12 millennia ago, of farming: a revolution more seismic even than those later ones it enabled. If Buddha, Christ etc were highly ‘realised’, those touched by their presence had the daunting task of communicating things beyond their ken. It’s easier to speak of turning water to wine, of blinding lights and voices in the sky than to peddle abstractions like ‘enlightened being’, ‘non dual awareness’ and ‘direct transmission’ from – take your pick – ‘God’/’The Universe’/’The Absolute’ etc. And that’s before we even get to the tendency of tales to grow taller with each telling.

- Relax. Exposure to the wisdoms – and these may be many and profound – of a cult leader will not of itself carry you off into slavery. In any case, this particular ship has sailed and foundered. Cult Cohen is no more, though some of the more vigilant of its former crew are keeping close tabs on their erstwhile skipper.

- I’ve found psychological generalisations about charisma to be partially but never fully convincing. A woman I read of – probably related to the British royal family – who’d known both Churchill and Hitler said Adolf had far more of the stuff. Which would tie in with my belief that one aspect is doubtlessness. Most of us lead lives of paralysing ambivalence. The impact of encountering those rare individuals for whom absence of doubt is not a front but the very air they breathe can stop us in our tracks and leave us agape. Even this, however, does not adequately explain the charism of men like Osho, Maharishi and Andrew Cohen – or of women like Mother Meera, the hugging Amma or Vimala Thakar. For that, I submit, we must leave the comfort zones of our cherished degrees in psychology – be they Oxbridge or University of Life (Department of Hard Knocks) – and conclusions drawn from chinks in the walls of jail cells we call normal experience. We have to dive deeper, and even then may never really know; never hold in our minds at one and the same time both the extraordinary presence and depth of these people, and their frequently flawed humanity. But we will at least have loosened our needy attachment to the glib and cosily reductive.

- Andrew’s passion is jazz, at its best and most exciting the music form above all others where the artists stand at the very edge of their experience. As for the artist he was most fascinated by, Miles Davis; there we have a pairing worth exploring: two men of audacious genius, neither without his demons.

- My own alma mater, having spent squillions on a spanking new computer engineering building, thought to call it the Sheffield Hallam Institute of Technology. The name got a surprisingly long way (OK, maybe not so surprising to old hands) before its acronym was spotted. And according to a TV drama about Mary Whitehouse, before settling on NVALA this anti porn crusader had dallied with the campaign name, Clean Up National Television.

- The quality of food on retreats and in spiritual communities is (usually) high. There are reasons for that. At a mundane level, with fewer of the world’s distractions, the simple pleasures of eating matter. (And the palate is sensitised.) At another level, collective partaking of sustenance is symbolic of that deep communion between brothers and sisters in existential inquiry. On another level yet, quality of awareness is reflected in the kitchen – not least in simple tasks, like getting the rice just so, which so often trip us up: betraying a deeper lack of what we now call mindfulness. In zen monasteries, I’m told, the cook is second in seniority only to the abbot.

- I’ll say more on contemplation in part 5. For now it suffices that people almost never come together in conditions where the object of inquiry is more important than the diverse egoic agendas at work. And the chances of those agendas being fully absent, even for a few moments, are infinitesimally small. (Broadly speaking there are gender differences in the ways they play out but it’s a very superficial understanding of ego which sees this as a ‘man thing’.) Total suspension of ego seldom happened, not even in these rarified conditions, but when it did the shift was palpable. As was its abrupt cessation. Such states of radically objective inquiry, I came to realise, are more likely on retreats than in any other situation. Though about as stable as a candle flickering in a wind tunnel, that they can occur at all opens up an astonishing possibility for every arena of human enquiry: scientific, philosophical, moral, political.

Extraordinary experiences Phil – and having dipped into Mr Cohen’s website I think I have an inkling of his calm, powerful presence and the force of his insight. I am, however, stuck with how his teaching relates to the world that most of us inhabit – particularly re responsibilities to others – although I am sure he will have clear views (if that is the right word) on that. How were you prepared to leave the 8 day retreat – or is that in the next episode?

Hey Bryan. On the question of how his teachings related to the world, Andrew Cohen had much to say. Meditation as metaphor for enlightenment is standard fare within the eastern traditions he’d absorbed. (I’ll speak a little in part 5 of his ability to plunge a room of hundreds of people into such deep states of consciousness. According to others I spoke to after the retreat – folks new to his teachings but, unlike me, having spent years and even decades with other teachers – his magic here made him quite exceptional, even when measured against titans like Osho.)

Meditation as metaphor confronts us, he insisted (see also part 3), with the first of life’s two major questions: Who Am I? Though Andrew said a lot, on this retreat and in others, on the second – How Shall I Live? – his teachings were in 1996 still evolving. Again I’ll speak of this in the next thrilling episode.

Your final question is uncanny. On the final teaching of the retreat one woman spoke of her awe at, to borrow from Sinead I-Feel-So-Different O’Connor, ‘all you have spread before me’. But she went on to ask, “but what do I do with it”? The manner and tone of its framing made clear she meant the question in a highly personalised sense.

“I don’t know how to begin”, The Man replied, “responding to that question”.

‘How should I live?’ (In the light of such insight) is logically the next question.

He believed that his inquiries into that second question – using the vehicle of hundreds of students who’d follow him to the ends of the earth – set him apart from every other guru.

I have to say that I’m conflicted over ‘guru’ figures. On the one hand, they seem to be prone to very human failings such as avarice, materialism and sex, which reduces confidence in their claims to ‘advancement’. On the other hand, although e.g. Buddhism has many examples of solitary ‘saints’ especially in Tibet, there seems to be a presumption that human society is pre-eminent. (Sangha). So I’m not sure if going on your own is possible, while joining a group involves accepting beliefs which you might not agree wholeheartedly with.

As for ‘peak experiences’ and other such encounter with actual reality, David Hay for one has attempted to analyse their frequency, and it seems that quite a large percentage of the population have such experiences. Discussion of such inevitably leads on to the role of science in being able to discuss such events, whether the brain equals the mind, (extremely doubtful), near-death experiences, PSI, reincarnation etc. are all grist to the mill, and I look forward to your future comments on these subjects – which should consume a bit of time, while we are hanging around to die ( © Townes van Zandt)

I think by now we will have lost most of your materialist Marxist readership, and after three strongish beers you are about to lose me too.

Stay safe, stay cool.

Thanks Jams. Many years ago I skim read David Hay’s Something There. I’ll take another look if I can spare the time from monitoring ruling class devilry!

As for materialist Marxists, well, I’m one myself – though I admit you’d be hard put to tell from these writings! That said, I did try in part 2 to clear up some of the confusion arising from two very different takes on the word, materialism.

Nevertheless, many and perhaps even most on the spiritual scene implicitly or explicitly take the view that ‘politics’ is a distraction from the ‘real business of spiritual practice’. In this they reflect, often in distilled form, the widespread and thoroughly bourgeois fantasy that it is possible to be ‘non political’.

(Andrew Cohen was dismissive of ‘politics’. Which left him reduced, on matters even he couldn’t ignore – like Iraq 2003 – to (a) parroting imperialist narratives dressed up as schoolyard morality tales on ‘taking out a bully’ and (b) assuming all who opposed that genocidal asset grab to be vapid ‘green meme’ wishy washy pacifists.)

How can the very real phenomena I try to speak of here be squared with my thoroughly materialist understandings of history, including the shit going down right now? I don’t know, man. That’s what I’m working on with these posts.

Yes. Buddhism used to have this problem too – being attacked for withdrawing from the world. In the last 50 or so years though, it has become readier to act in the mundane world (Vietnam War, notably).

However, I see no good reason why a practising Marxist has to necessarily be a thorough going materialist. Materialism is not essential to social revolution, although I can see why the two can be seen as being closely related – as Marx himself was an atheist, and described religion as the opiate of the people – a disincentive to revolution. But a dedication to his system can be combined with a spiritual practice without any crashing of the gears, and can be an added incentive to achieve social justice.

On a slightly different tack, I find the kind of aggressive atheism and materialism as practiced by the likes of Dennett and Dawkins to be both slightly desperate ultimately unconvincing. I imagine it is (quite logically) driven by the large body of fundamentalist Christians in the US who have posed a real threat to the practice of science there at least since the ‘Scopes’ Monkey Trial era.

There are lots of discussion points too around the revelations of quantum theory which seem to indicate that matter is basically pretty insubstantial and unreal once you get right down to basics, and although I don’t see that as a link to spirituality, it indicates that we have a long way to go to understand what we are.

There’s no end to all this, so I’d better stop now and give someone else a chance.

Talk of Dawkins – a gifted communicator of scientific thought – brings us to the heart of my materialism (and I think Marx’s). Dawkins is an idealist (another word of dual meaning but I speak epistemologically). He locates, for instance, Islamism in the Koran; not in the material context of Western imperialism. In this he is wrong. His mistake, one I too have made in respect of Islamism, is that of ahistoricism, and of prioritising ideas over matter. Granted, it’s a vulgar grasp of Marxism which understands the interplay between ideas and matter as crudely and mechanistically one-way, but in the last analysis I look to the latter in my understanding of history. I disregard the highfalutin protests of politicians and media and, like Monsieur Poirot, follow the money.

My favourite book of Dawkins is not Selfish Gene or Blind Watchmaker but Greatest Show on Earth, the only one dedicated to laying out the evidence and reasoning underpinning Darwinism. My least favourite is the God Delusion but even here I’ll cut him some slack. Dawkins did not initially go looking for a scrap with theism. (He clearly enjoys a cordial relationship with former Archbishop of C, Rowan Williams.) What set him off on an ‘aggressive’ stance was the insistence in some states of America – and signs of similar movements in other Western countries – that ‘creationism’ (the term now so embarrassing it had to be given a makeover as “intelligent design”) be accorded at least equal status with evolutionary theory in school curricula.

It’s significant that Dawkins is as one with such otherwise very different thinkers as Noam Chomsky, Jordan Peterson and the late Christopher Hitchens in his rejection of postmodernism. If there’s no such thing as truth, and all is simply ‘narrative’, then of course voodoo or Genesis are as valid as physics. We’re no longer looking to empirically observed predictive power as a criterion because, hey, who knows what skewed observables our senses – their thresholds marvellously enhanced by state of the art technologies – might be delivering? And who knows what skewed understandings we might be bringing to bear on what we observe?

Such questions are not to be shrugged aside, especially in challenges to the logical positivism dominating social science up to the sixties. That’s the bit postmodernism got right in my view. Where it went wrong is in jettisoning any notion of objective truth. (I see ‘critical realism’ as a row-back from the excesses of postmodernism, including the paradox at its heart: that if I claim there’s no such thing as truth, how do you assess the status of my claim?)

Which brings me to the quantum stuff.

Unless we’re well versed in theoretical physics, we do well to mind how we go on quantum mechanics ground. I’ve known folk who know less than I do – which is saying something – go gaga over cherry picked observations from QM. (Postmodernists used to love doing this. They’d stuff their papers – peer reviewed, let me add, for the benefit of those credulous souls who implicitly see PR as gold seal of A. – with refs to natural science phenomena about which their total knowledge could be written on the back of a stamp. The smarter of them wised up after the Sokal hoax, mind!) Yes, Borg et al did throw up much we still can’t get our heads round. (Particles acting as energy on the third Monday and Wednesday after a full moon, as matter the rest of the time except on the last Friday before Michaelmas Day … behaviour akin to me throwing a punch in a bar, and somebody getting a bloody nose in a pub three miles away.) And, yes, in physics especially, the ratio of speculation to empirical observation – and only the crudest empiricism denies that the two are always needed – is now high. Nevertheless, what distinguishes physics from voodoo (and science fiction) is that empirical methods still apply. That’s why we get excited when theories once unfalsifiable hold up, once technological advances allow them to be tested.

(Which reminds me to say how thrilled Darwin would have been to see how thoroughly, elegantly and brilliantly his theories have been upheld by subsequent technologies and methods beyond his wildest dreams. Dawkins done good here. Chapter 4 of Greatest Show, for instance, in its discussion of “clocks”, lays out in all their beauty the reasoning and measurement devices by which we are not only able to date events millions of years ago but, by cross checking one ‘clock’ against another, do so to a very high degree of accuracy. Elsewhere in the same book he gives pristine examples of how the acid test of predictive power can be applied even in a field whose subject is the past. On a volcanic island a flower is discovered. For that flower to be fertilised, natural selection of random genetic mutation dictates that some highly adapted insect or bird must exist. The search is on. Lo and behold, a second new species is found!)

I’ll be front of the queue when it comes to calling out crude materialism, be it vulgar (non dialectical) Marxism, or more widespread failure to distinguish crass empiricism from empirically based reasoning. Equally though, I’ve no truck with vulgar idealism – not, I hasten to add, that I’m accusing you of peddling that! Where this takes me in the context of these posts I still can’t rightly say – let none accuse me of shrinking from standing at the edge of my own experience! – but I thank you, not for the first time, for a comment that helps me clarify my thinking.

Yeah. The point about physics that I was trying to make is that when you get down to quarks, whatever they are, you are getting into explanations of the mathematics which are something like “they are twists in space” – whatever that can be -i.e. matter becomes sort of not really there – reality becomes in some sense unreal or insubstantial. Also, of course, a mathematical formula is just a map, not actual reality. So the whole scientific investigation of reality peters out into a new sort of (almost) mysticism.

As for Dawkins, et al, my objection to their style of thinking is that will only accept as real the findings of science – but science only deals with the things it can deal with – things that can be modelled by mathematics. Thoughts (for example) are therefore outside scientific reality despite the efforts of Freud and neuroscience. Unfortunately that doesn’t stop these pundits like Dawkins from making definite pronouncements on the subject.

So anything outside that mode of ‘modelling’ (and there are centuries of reports of a variety of experiences such as NDE’s, poltergeist phenomenon, spiritual [how I hate that word] experience etc,) is invisible to science. This is not really helpful to understanding. A good site for philosophical musings on this subject is:

http://ian-wardell.blogspot.com

It’s shameless of me. I used my Godlike prerogative of being able to come back and edit my own comments to hone and add to my words on Dawkins, materialism, science, postmodernism, life, death and the universe. With heroic renunciation, despite it being Beethoven’s 250th the other day, I desisted from squeezing him in too!

To be fair, I think you’re in danger of making an Aunt Sally of Dawkins. (Many do.) As set out earlier, I have my own beefs with him but I don’t think he says (in effect) “if it ain’t science it ain’t real”. He was perfectly happy, for instance, with the myths of Genesis being taught in school RE classes. Only when, with no small help from the half-baked end of postmodernism, a reactionary “Intelligent Design” movement started to gain serious traction, and insist Darwinian theory and Genesis offered different but equally valid accounts of how life began, did he step into the ring to defend the overwhelming superiority, by any sane standards, of evidence for natural selection of random genetic mutation over that for biblical accounts. Does this mean he regarded the latter as worthless? I’m told, though I can’t evidence this, that Dawkins bemoans declining knowledge of scripture. Bible, Koran, Vedas etc remain important texts for all kinds of reason, including (as with Shakespeare) the social glue of shared cultural matrices.

On that last, who does not take wicked delight in the downfall of an overpromoted toady, his old boss lost to management shake up? When New Boss sees no merit in Old Boss’s wonder boy, the words of Exodus 1:8 ring down the ages, their pithy eloquence and to-the-minute pertinence amplified by the estrangements of archaic grammar:

I try and read of your posts Phil, but this one will have me rereading and rereading. Utterly compelling theme and writing. Thank you.

Kind of you to say so, Kevin. These few posts aren’t everyone’s cup of tea, I know, but even at a purely technical level this one in particular has been more challenging than anything else on this entire site.

It shows. I’ve tried TM and Hanmi Buddhism, at more of a surface level than your deep dives. The Buddhism practice prompted the ‘How should I live?’ question, and ensured its persistence down the years. Your retrospective explorations are a treasure and a new lure.

You’re too kind – but I get so much stick I’m not gonna turn down a compliment. Thanks again man!

Like Kevin, I have to say that it is pretty courageous of you to lay your life out for potential criticism like this, Phil, especially given that it is at a tangent from Marxism and socialism. But it makes for interesting reading, especially for those of us who have made similar choices.

PS On re-reading the earlier parts of this sequence, I see that you have anticipated much of my later comments re Marxism and religion. I read them at the time but my short term memory must be getting worse – either that or it’s the drink! They say that drinking gives you grain bandage, – drain garbage – rain gamboge . . .

(:-)